Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

Part 8: More Mapping Information

By Michael O'Leary; The Regimental Rogue

Introduction

The preceding article in this series showed how to take battlefield location information from a soldier's letters, unit war diaries or other sources, and to find those locations on the applicable First World War maps. Maps of the era, not unlike today's maps, either highway or topographical, are dense collections of information presented in a graphical manner. Each and every map is published with a key to the symbols used in its own construction, and while many aspects will be familiar to someone with a good understanding of modern maps, others will be specific to the wartime map's period or usage.

The images presented below (click the smaller images for larger versions) present map data that will help you familiarize yourself with the symbology found on First World War maps. When working with a fullsized wartime map, always check the marginal information for its particular legend to add to your familiarity with the range of symbols and colours in use. Building that knowledge will help you better "read" the many cropped map images you may find on line or in reference works that are not always presented with their original legends.

Military Sketching Made easy and Military Maps Explained; 1911

From publisher Gale & Polden's Military Series, this volume by Colonel D.H. Hutchinson, Indian Army, was a guide to the map using and field sketching skills expected of officers in the British Army. This chart of conventional signs was reproduced from the "Manual of Map Reading and Field Sketching" by permission of the Controller of His Majesty's Stationery Office.

Conventional Signs & Terms Used in Military Topography.

Source: Military Sketching Made easy and Military Maps Explained; 1911.

The 1914 Field Service Pocket Book

This volume, orginally printed on the eve of the Great War, and republished in 1916, provides a standard legend for the use in field sketching. Field sketching was an expected skill for officers, and formed the basis of mapping and battlefield reporting in much of the British Empire.

The 1926 Field Service Pocket Book

The 1926 Field Service Pocket Book, expanded from the wartime issues and was built upon the lessons learned during the First World War. Among the other data included in this volume was a page introducing some of the scales used for military maps. It is important to consider the scale of the map you are examining as it will affect your understanding of time and distance as the soldier or unit you are researching traverses the terrain depicted by the map. One helpful aid is to create your own set of rulers from the scales found at the bottom of the maps you examine, and use these to measure distance on the map in the correct scale for each map.

Scales and Rates of Movement (1926).

Scales and Conventional Signs. Note the comparative scales for standard rates of trotting and marching on the bottom side of scales 2 and 5, respectively.

Source: 1926 Field Service Pocket Book.

Conventional Signs & Lettering Used in Field Sketching (1926).

The Principal Conventional Signs to be used on Trench & Artillery Maps (1926).

The Principal Conventional Signs to be used on Trench & Artillery Maps. Source: 1926 Field Service Pocket Book.

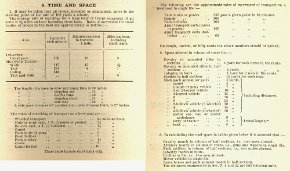

Time and Space: Men, Animals and Vehicles (1926).

Although not strictly map information, the data in the next attached image will assist a researcher in understanding the very important aspects of mobility and speed, and their effect on the perceived size of a battlefield area. Much movement in the First World War occurred at the rate of marching troops or animals, whether the latter were carrying mounted soldiers, drawing wagons or carrying loads of stores themselves. An understanding of rates of movement for various bodies of troops is important is assessing how far units may have travelled on the days they were on the march, and how much time on each of those days was dedicated solely to the function of battlefield mobility through marching.

Time and space data for the movement of men, animals and vehicles. Source: 1926 Field Service Pocket Book.

Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Introduction

- Part 1: Find your Man (or Woman)

- Part 2: The Service Record

- Part 3: Court Martial Records

- Part 4: War Diaries and Unit Histories

- Part 5: Casualties

- Part 6: Researching Honours and Awards

- Part 7: Deciphering Battlefield Location Information

- Part 8: More Mapping Information

- Part 9: Matching Battlefield Locations to the Modern Map

- Part 10: Service Numbers; More than meets the eye

- Part 11: Rank, no simple progression

- Part 12: Medals; Pip, Squeak, Wilfred and the whole gang

- Part 13: Evacuation to Hospital

- Part 14: The Wounded and Sick

- Part 15: Crime …

- Part 16: … and Punishment

- Part 17: Battalions and Brigades, Companies and Corps

- Part 18: Photo Forensics: Badges and Patches

- Part 19: Veterans Death Cards

- Part 20: The Vimy Pilgrims (1936)

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Vimy Memorial

- Dieppe Cemetery

- Perpetuation of CEF Units

- Researching Military Records

- Recommended Reading

- The Frontenac Times

- RCR Cap Badge (unique)

- Boer War Battles

- In Praise of Infantry

- Naval Toast of the Day

- Toasts in the Army (1956)

- Duties of the CSM and CQMS (1942)

- The "Man-in-the-Dark" Theory of Infantry Tactics and the "Expanding Torrent" System of Attack

- The Soldier's Pillar of Fire by Night; The Need for a Framework of Tactics (1921)

- Section Leading; A Guide for the Training of Non-Commissioned Officers as Commanders and Rifle Sections, 1928 (PDF)

- The Training of the Infantry Soldier (1929)

- Modern Infantry Discipline (1934)

- A Defence of Close-Order Drill (1934): A Reply To "Modern Infantry Discipline"

- Tactical Training in the British Army (1901)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1903)

- Discipline and Personality (1925)

- The Necessity of Cultivating Brigade Spirit in Peace Time (1927)

- The Human Element In War (1927)

- The Human Element In Tanks (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- The Sergeant-Major (1929)

- The Essence Of War (1930)

- Looks or Use? (1931)

- The Colours (1932)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- Origins of Some Military Terms (1935)

- Practical Examination; Promotion to Colonel N.P.A.M. (1936)

- Company Training (1937)

- Lament Of A Colonel's Lady (1938)

- Morale (1950)

- War Diaries—Good, Bad and Indifferent

- Catchwords – The Curse and the Cure (1953)

- Duelling in the Army

- Exercise DASH, A Jump Story (1954)

- The Man Who Wore Three Hats—DOUBLE ROLE

- Some Notes on Military Swords

- The Old Defence Quarterly (1960)

- Military History For All (1962)

- Notes for Visiting Generals (1963)

- Hints to General Staff Officers (1964)

- Notes for Young TEWTISTS (1966)

- THE P.B.I. (1970)

- Standing Orders for Army Brides (1973)

- The Time Safety Factor (1978)

- Raids (1933)

- Ludendorff on Clerking (1917)

- Pigeons in the Great War

- Canadian Officer Training Syllabus (1917)

- The Tragedy of the Last Bay (1927)

- The Trench Magazine (1928)

- Billets and Batman (1933)

- Some Notes on Shell Shock (1935)

- Wasted Time in Regimental Soldiering (1936)

- THE REGIMENT (1946)

- The Case for the Regimental System (1951)

- Regimental Tradition in the Infantry (1951)

- The Winter Clothing of British Troops in Canada, 1848-1849

- Notes On The Canadian Militia (1886)

- Re-Armament in the Dominions - Canada (1939)

- The Complete Kit of the Infantry Officer (1901)

- The Canadian Militia System (1901)

- The Infantry Militia Officer of To-day and His Problems (1926)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- British Regular Army in Canada

- Battle Honours (1957)

- Defence: The Great Canadian Fairy Tale (1972)

- The Pig (1986)

- Standing Orders for the Fortress of Halifax, N.S.; 1908

- Medals and Badges - Fakes and Copies

- Army Punishments Part 1 - • Part 2

• C.A.R.O. No. 6719 - Campaign Stars, Clasps, The Defence Medal and the War Medal 1939-45

[an error occurred while processing this directive]