Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

Part 14: The Wounded and Sick

By Michael O'Leary; The Regimental Rogue

Introduction

"The total number of cases receiving hospital treatment up to August 31, 1919, was 539,690 of which 144,606 were battle casualties and 395,084 of disease."

Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services, by Sir Andrew McPhail, 1925 (emphasis added).

Canada sent a total of 418,606 troops overseas in the First World War. In comparison, the number of hospitalizations reached 539,690 (or 129 % of the number of deployed troops) in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). This number is further divided into 144,606 battle casualties and 395,084 soldiers being hospitalized for various diseases. While these numbers do not include minor illnesses that were treated by unit medical officers, they do include multiple hospitalizations for many individuals. These statistics do, however, emphasize the seriousness of disease and sickness on the battlefield of the First World War, in an era before the use of effective antibiotics. Illnesses that might be considered minor today (or almost eradicated in the Western world by improved diet and medicine) could hospitalize a man for weeks or months before he returned to duty on the front lines.

This article will look at some of the causes of the frequency of wounds and types of illnesses that affected Canadian soldiers of the First World War. Researchers examining a soldier's service record are reminded that consideration must be given to the era, the state of development of medical care and the unavailability of many of the diagnostic tools and treatment methods that might be found in a modern doctor's office or hospital.

Statistics; Casualties from Disease and Wounds, and Deaths

The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services provides the following statistics. The source, printed in 1925, also notes that figures are subject to technical revision. Discrepancies in classification of individual cases initially recorded as "killed accidentally, "suicide", or other causes can be adjusted following review giving different number depending on source and date of publication.

Total casualties Overseas from Disease and Wounds (to 31 March 1923)

| Officers | Other Ranks | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases of disease | 19,100 | 375,984 | 395,084 |

| Died of Disease | 175 | 3650 | 3825 |

| Percentage of deaths by disease to number of cases of disease | .91 % | .97 % | .96 % |

| Cases of wounded | 6347 | 143,385 | 149,732 |

| Died of wounds | 819 | 16,363 | 17,182 |

| Percentage of deaths by wounds to number of cases of wounds | 12.90 % | 11.41 % | 11.6 % |

Deaths Overseas (to 31 March 1923)

| Officers | Other Ranks | Total | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease and other causes | 297 | 4663 | 4960 | 8.75 % |

| Killed in Action | 1776 | 32,720 | 34,496 | 60.92 % |

| Died of Wounds | 819 | 16,363 | 17,182 | 30.33 % |

| Totals | 2892 | 53,746 | 56,638 | — |

In summary, less than 1% of soldiers hospitalized for sickness died of their disease; and of those sent to hospital wounded, only 11.6% later died of their wounds.

Wounds

The following table from the Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services shows the distribution of wound types experienced by officers and other ranks of the CEF:

| Officers | Other Ranks | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 907 | 21,377 | 22,284 |

| Chest | 230 | 3550 | 3780 |

| Abdomen | 78 | 1317 | 1395 |

| Pelvis | 10 | 43 | 53 |

| Upper extremities | 1895 | 49,615 | 51,508 |

| Lower extremities | 1809 | 41,843 | 43,652 |

| Wounded, remained at duty | 904 | 6698 | 7602 |

| Wounds, accidental | 107 | 2140 | 2247 |

| Wounds, self-inflicted | 6 | 723 | 729 |

| Effects of gas fumes | 368 | 10,988 | 11,356 |

| 6312 | 138,294 | 144,606 |

Further detail is provided on the numbers of amputations performed:

- Both legs - 47

- Both legs and both arms - 1

- One leg - 1675

- One foot - 232

- Both feet - 11

- Both arms - 6

- One arm - 667

- One hand - 141

Diseases

The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services offers details of the following diseases which afflicted the soldiers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force:

- Typhoid: Typhoid fever is transmitted by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person. Historically a devastating disease among soldiers at war (in the South African War one in seven afflicted soldiers died), typhoid was controlled during the Great War by the use of vaccines which were improved during the war for better effectiveness. As a result of this treatment, only 442 Canadian fell ill to typhoid, and only 16 died of this disease.

- Dysentery: Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine which cases severe diarrhoea and abdominal pain. During the war there were 1124 cases among Canadian, of which 14 were fatalities. Sick troops were isolated at special centres and the spread of the disease was combated by sanitary measures.

- Cerebro-Spinal Meningitis: Cerebro-Spinal Meningitis, or inflammation of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord can be caused by viruses, bacteria or other microorganisms. The CEF experienced 399 cases of Meningitis, of which 219 died.

- Jaundice: Jaundice, evidenced by a yellowish pigmentation of the skin, is caused by caused by hyperbilirubinemia (increased levels of bilirubin in the blood). Originally classified as a "fever of unknown origin", diagnostic work during the war established the cause of the disease, confirmed its infectiousness, and also that it was spread by rats on the battlefield via their urine (and by the afflicted soldiers in the same manner).

- Trench Fever: Trench Fever is transmitted by body lice and subjects the afflicted person to pain and stiffness in the muscles of the back and shoulders which descended violently to the legs, faintness and vertigo, headaches, fever, nausea and constipation. Despite the patient's misery, conditions normally subsided within days and he would be discharged to duty on the third day. Some patients had one of more relapses. The CEF recorded 4987 cases of confirmed Trench fever (there was another 15,355 cases of fevers of unknown origin), but "almost none" were fatalities.

- Tetanus: Tetanus, also known as lock-jaw, is characterized by muscular stiffness around the site of wounds, stiffness of neck and jaw, and muscular spasms. Treatment and prevention was applied through injection of an antitoxin and the complete and early excision of gunshot wounds.

- Trench Foot: Trench Foot, caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to wet conditions, was a workplace hazard on the battlefields of the First World War. It was brought under control through the use of punitive measures against units (stoppage of leave) where cases were discovered and this encouraged units and their soldiers to develop habits to avoid the condition. Trench Feet accounted for 4987 casualties in the CEF, but only two deaths.

- Trench Mouth: Trench Mouth, or necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, is an acute periodontal disease, an infection of the gum tissue. Spread of the disease was checked in camps in England and later in France and Belgium by dental care and also by orders that required the edge of every glass and mug in public drinking places to be dipped in boiling water in the presence of the customer. Those establishment which were not prepared to meet this requirement were placed out of bounds. This method of sterilization was effective and the disease controlled.

- Other Infectious Diseases:

- Influenza: Influenza was a significant killer during the war years and, late in the war, the 1918 flu pandemic was felt by all the deployed armies. There were 45,960 cases of influenza in the CEF and 776 of those were fatalities.

- Pneumonia: Pneumonia was diagnosed in 4712 cases, resulting in 1261 deaths.

- Mumps: There were 9644 cases of Mumps.

- Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis of the lungs was responsible for 3123 cases of the disease and 176 deaths.

- Measles: Measles saw 2186 men hospitalized, and resulted in 30 deaths.

- Scarlet Fever: There were 4 deaths out of the 271 cases of Scarlet Fever.

- Rheumatic Fever: There were 1258 cases of Rheumatic Fever and two deaths caused by the disease.

- German Measles: German Measles, known today as Rubella, accounted for 2641 cases.

- Diphtheria: 1701 members of the CEF were diagnosed with diphtheria and 18 died from the disease.

- Malaria: There were 460 cases of malaria in the CEF.

- Chicken Pox: 109 cases of chicken pox were diagnosed.

- Smallpox: Ten cases of smallpox resulted in the death of one soldier of the CEF.

- Tonsilitis: There were 10,473 cases of tonsilitis among the soldiers of the CEF.

- Insanity: 1683 men of the CEF were determined to be insane.

- Nervous Diseases: The generic description of "nervous diseases" was applied to 8513 cases.

- Disorderly Action of the Heart: The ambiguous description of "disorderly action of the heart" was recorded as cause for 4675 men being treated by the medical system.

- Diseases of the Skin: Various unclassified diseases of the skin accounted for 9471 individual cases requiring treatment in the CEF.

- Lice: Lice, bringers of discomfort more than any other effect, quickly infected entire battalions in the close living and sleeping conditions of trenches and billets. The images of itching soldiers and men searching their clothing for the lice and their eggs to free themselves of their tortuous activities are well ingrained in societal memory of the Great War's trench life. Dry heat applied to clothing, at 60ºC, was enough to sterilize uniforms to relieve men of the pesky creatures.

- Scabies: Scabies, a contagious skin infection caused by a parasitic mite, developed in the field during the First World War because the medical profession had become unfamiliar with its early signs and many soldiers will only report sick after a condition is too painful to endure, by which time they were probably sharing the disease with their section mates. The medical system treated 9559 cases of scabies, and the establishment of central baths helped to control the disease among the soldiers of the CEF.

Shell-Shock

During the First World War, shell-shock became the catch-all term for a wide variety of nervous conditions which, at various times were identified as ranging from "cowardice" to "maniacal insanity." While modern medicine is no more certain of effective diagnoses and treatment, the medical system of the Great War was not prepared for the range of possible symptoms or the reactions of patients or commanders to shell-shock. The medical system also found itself in the unenviable position of certifying men who appeared well enough at the time of examination to be fit to stand trials for cowardice, which in some cases led to their executions.

Identification and treatment of psychological illnesses was outside the experience of most of the medical officers in the front lines, who had to deal with cases as they appeared. Later, with the realization that shell-shock was a disease, or perhaps better described as a range of diseases and medical conditions, it was categorized as "shell-shock," "hysteria," or "neuresthenia." The growing readiness of the medical system to treat shell-shock patients with care was countered in 1917 by orders that attempted to quash the diagnosis (because it was suspected as a malingerer's choice of malady to fake). Those orders read:

In no circumstances whatever will the expression "shell-shock" be made use of verbally or be recorded in any regimental or other casualty report, or in any hospital or other medical document except in cases so classified by the order of the officer commanding the special hospital for such cases." (Report O.M.F.C. 1918)

Eye and Ear Injuries

Wounds of the eye, in themselves, were not common because they were usually associated with more significant trauma to the head, resulting in death. Within the CEF, 66 cases of blindness were recorded, with a further 476 men losing one eye. Ten others lost an eye as part of more general injuries, and there was one case of a man wilfully blinding himself. Cases of diseases of the eye totalled 6547 members of the CEF, but no deaths were recorded from this cause.

Men who lost their sight were treated at St. Dunstan's Hostel, where they were trained to live without their sight and were also taught a trade if they so desired.

Diseases of the ear accounted for 5708 hospital admission, of which 19 resulted in fatalities.

Self-Inflicted Wounds

The CEF recorded 729 cases of self-inflicted wounds of which six were by officers. The determination of the chain of command to prevent these instances was so strict that any medical officer identifying a possible case of self-inflicted wound was required to report it, and the patient was immediately placed under arrest awaiting court martial.

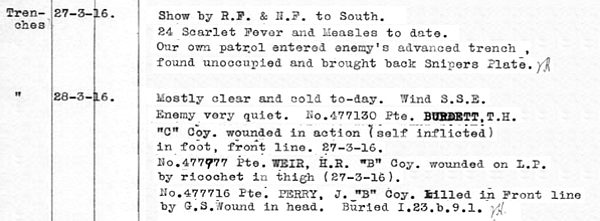

An excerpt from the War Diary of The Royal Canadian Regiment, showing the entries for 27 and 28 March 1916. The entry on 28 March notes the self-inflicted wound of 477130 Private T.H. Burdett.

The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services describes how a soldier intending to inflict a wound upon himself might do so:

" A man would fasten his rifle in a fixed position, discharge it, and observe where the bullet struck. He would then place the least serviceable part of his body in the line of fire and discharge the rifle again."

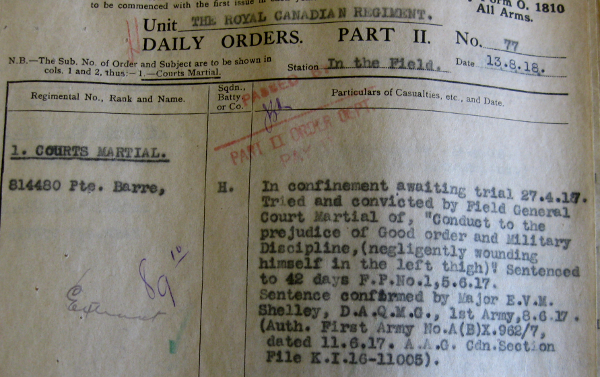

An excerpt from the Part II Daily Orders of The Royal Canadian Regiment, showing the entry for the Court Martial of 814480 Private H. Barre for a self-inflicted wound.

There was another, less easily detected, type of "self-inflicted wound" that might ensure a man spent lengthy periods in hospital instead of in the front line trenches …

Venereal Disease

The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services states the following for the incidence of venereal disease:

In the Canadian army overseas during the period of the war there were 66,083 cases of venereal disease, of which 18,612 were syphilis; this yields a rate of 158 per thousand, and for syphilis alone 4.5 per cent or 45 per thousand."

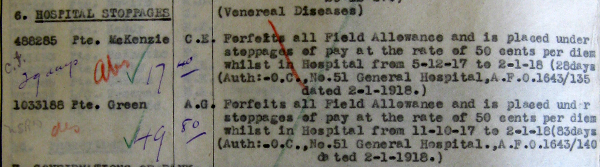

In an attempt to curtail the incidence of venereal disease, soldiers of the CEF forfeited 50 cents per day of their pay plus field allowances while in hospital for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases.

An excerpt from the Part II Daily Orders of The Royal Canadian Regiment, showing the entry for the Hospital Stoppages (of Pay) for two soldiers during their hospitalization for venereal disease.

Poison Gas

The use of poisonous gasses is one of the strongest images we have been left with of the First World War. The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War; The Medical Services gives the figure of 11,356 for the number of wounded suffering from effects of gas fumes. This is 7.85 % of the total number of wounded. The volume doesn't provide a number for deaths directly attributed to gas, but infers that the progress of counter-measures and strict adherence to anti-gas drills effectively countered the enemy's progress in use of gas types and quantities.

The Official History; The Medical Services offers the following points on these principal gas types and their effects on soldiers:

- Chlorine: "On 22 April … the alarm was great, but the casualties were not numerous."

- Phosgene: "Choking, coughing … inability to expand chest … vomiting … pain behind sternum … cyanosis … The development of these dangerous symptoms may occur after many hours' delay, and sometimes with an unexpected rapidity … Death, which may be proceeded by mils delirium or unconsciousness."

- Mustard gas: "Death is never the direct result of the action of the poisonous vapour … from the second day onward through the first and second week severely affected men may die, but only as a result of secondary bacterial infection … Death is relatively uncommon … 65 per cent were fit for discharge before the end of the fifth week."

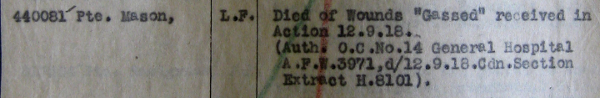

An excerpt from the Part II Daily Orders of The Royal Canadian Regiment, showing the recording of the "Died of Wounds 'Gassed'" death of 440081 Private L.F. Mason at No. 14 General Hospital.

Medical Categories

Soldiers who survived hospitalization would be subjected to medical examinations for the purpose of determining their fitness for duty. Although the intent of the system was to return every capable soldier to his front line unit, the medical system categorized soldiers according to the nature of duties they were fit to perform. The receipt of a medical category could then lead to reassignment to a new trade and to a new unit for further service. Alternatively, it might lead to discharge and return to civilian life.

The following excerpt from Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War 1914-1919; The Medical Services outlines the medical categories assigned to soldiers in the First World War. The volume was published by Authority of the Minister of National Defence under direction of the General Staff. The excerpt can be found on pages 211-212 of the volume, formatting in bulleted lists has been added for clarity:

"For the purpose of ascertaining the physical condition of each soldier and his value as a reinforcement a system was established early in 1917 by which men were assigned to groups according to their fitness for service. Five medical categories were created, A, B, C, D, E, to include, respectively, men who were fit for general service; fit for certain kinds of service; fit for service in England; temporarily unfit but likely to become fit after treatment; and all others who should be discharged.

"Category A was divided into four classes 1, 2, 3, 4, which contained respectively:

- men who were fit for active service in respect of health and training;

- men who had not been in the field but only lacked training;

- casualties fit as soon as they were hardened by exercise; and

- boys who would be fit as soon as they reached 19 years of age."

"Category B was likewise subdivided into four groups, to include men:

- who were fit for employment in labour, forestry, and railway units;

- men who were fit for base units of the medical service, garrison, or regimental outdoor duty;

- men capable of sedentary work as clerks; or

- skilled workmen at their trades."

"In Category C were placed men fit for service in England only."

"In Category D were all men discharged from hospital to the command depot, who would be fit for Category A after completion of remedial training; and there was a special group to include all other ranks of any unit under medical treatment, who on completion would rejoin their original category."

"Category E included men unfit for A, B or C, and not likely to become fit within six months. It was a general rule that a soldier could be raised in category by a medical officer but lowered only by a board."

"A commanding officer could, however, raise a man in Category A from second to first group, since training alone and not medical treatment was involved. All soldiers of low category were examined at regular intervals and new assignments made."

"It was the function of the medical services to assign recruits and casualties to their proper categories. In April, 1918, when the demand for men became urgent, an allocation board was set up for the duty of examining all men of low category, and assigning them to tasks that were suitable for their capacity."

Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Introduction

- Part 1: Find your Man (or Woman)

- Part 2: The Service Record

- Part 3: Court Martial Records

- Part 4: War Diaries and Unit Histories

- Part 5: Casualties

- Part 6: Researching Honours and Awards

- Part 7: Deciphering Battlefield Location Information

- Part 8: More Mapping Information

- Part 9: Matching Battlefield Locations to the Modern Map

- Part 10: Service Numbers; More than meets the eye

- Part 11: Rank, no simple progression

- Part 12: Medals; Pip, Squeak, Wilfred and the whole gang

- Part 13: Evacuation to Hospital

- Part 14: The Wounded and Sick

- Part 15: Crime …

- Part 16: … and Punishment

- Part 17: Battalions and Brigades, Companies and Corps

- Part 18: Photo Forensics: Badges and Patches

- Part 19: Veterans Death Cards

- Part 20: The Vimy Pilgrims (1936)

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Vimy Memorial

- Dieppe Cemetery

- Perpetuation of CEF Units

- Researching Military Records

- Recommended Reading

- The Frontenac Times

- RCR Cap Badge (unique)

- Boer War Battles

- In Praise of Infantry

- Naval Toast of the Day

- Toasts in the Army (1956)

- Duties of the CSM and CQMS (1942)

- The "Man-in-the-Dark" Theory of Infantry Tactics and the "Expanding Torrent" System of Attack

- The Soldier's Pillar of Fire by Night; The Need for a Framework of Tactics (1921)

- Section Leading; A Guide for the Training of Non-Commissioned Officers as Commanders and Rifle Sections, 1928 (PDF)

- The Training of the Infantry Soldier (1929)

- Modern Infantry Discipline (1934)

- A Defence of Close-Order Drill (1934): A Reply To "Modern Infantry Discipline"

- Tactical Training in the British Army (1901)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1903)

- Discipline and Personality (1925)

- The Necessity of Cultivating Brigade Spirit in Peace Time (1927)

- The Human Element In War (1927)

- The Human Element In Tanks (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- The Sergeant-Major (1929)

- The Essence Of War (1930)

- Looks or Use? (1931)

- The Colours (1932)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- Origins of Some Military Terms (1935)

- Practical Examination; Promotion to Colonel N.P.A.M. (1936)

- Company Training (1937)

- Lament Of A Colonel's Lady (1938)

- Morale (1950)

- War Diaries—Good, Bad and Indifferent

- Catchwords – The Curse and the Cure (1953)

- Duelling in the Army

- Exercise DASH, A Jump Story (1954)

- The Man Who Wore Three Hats—DOUBLE ROLE

- Some Notes on Military Swords

- The Old Defence Quarterly (1960)

- Military History For All (1962)

- Notes for Visiting Generals (1963)

- Hints to General Staff Officers (1964)

- Notes for Young TEWTISTS (1966)

- THE P.B.I. (1970)

- Standing Orders for Army Brides (1973)

- The Time Safety Factor (1978)

- Raids (1933)

- Ludendorff on Clerking (1917)

- Pigeons in the Great War

- Canadian Officer Training Syllabus (1917)

- The Tragedy of the Last Bay (1927)

- The Trench Magazine (1928)

- Billets and Batman (1933)

- Some Notes on Shell Shock (1935)

- Wasted Time in Regimental Soldiering (1936)

- THE REGIMENT (1946)

- The Case for the Regimental System (1951)

- Regimental Tradition in the Infantry (1951)

- The Winter Clothing of British Troops in Canada, 1848-1849

- Notes On The Canadian Militia (1886)

- Re-Armament in the Dominions - Canada (1939)

- The Complete Kit of the Infantry Officer (1901)

- The Canadian Militia System (1901)

- The Infantry Militia Officer of To-day and His Problems (1926)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- British Regular Army in Canada

- Battle Honours (1957)

- Defence: The Great Canadian Fairy Tale (1972)

- The Pig (1986)

- Standing Orders for the Fortress of Halifax, N.S.; 1908

- Medals and Badges - Fakes and Copies

- Army Punishments Part 1 - • Part 2

• C.A.R.O. No. 6719 - Campaign Stars, Clasps, The Defence Medal and the War Medal 1939-45

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]