Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

Part 10: Service Numbers; More than meets the eye.

By Michael O'Leary; The Regimental Rogue

Introduction

The assignment of a regimental number, later referred to as service number, has been a consistent aspect of a soldierly existence for well over a century. The regimental number ensured that soldiers with common surnames and the same given names, or initials, would not be confused by the bureaucracy when it came to pay, promotions or punishment, along with all of the other personnel management activities of an army, past or present.

Service Numbers

Before the First World War, military units in Canada maintained internal rolls and ledgers that ensured regimental numbers were not duplicated within the ranks of each regiment. This approach was in effect in 1914 when new units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force were mobilized. When many new units begaun numbering enlisted troops in accordance with the accepted practices there was duplication between Corps, and many low numbers were assigned again and again across the country. As can be expected, this had the potential to result in a certain amount of confusion.

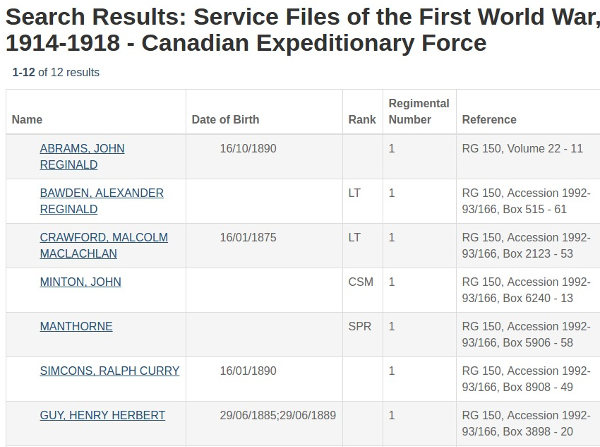

The Library and Archives Canada (LAC) database, Personnel Records of the First World War (1914-1918), can be used to demonstrate how many soldiers held individual numbers in the final accounting of the records, this does not include those whose service numbers were changed and are recorded under those later, unique, numbers. When the database is searched for service number "1", there are twelve results. Similarly, the service number "24" was held by 21 soldiers.

A search of the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) database, Personnel Records of the First World War (1914-1918) demonstrated that low numbers were often duplicated before the CEF started controlling the issue of number blocks to each authorized unit. A search for the service number "1" shows that twelve men are still identified by that number.

In 1915, a new system of service numbers for the Canadian Expeditionary Force was developed. Most units assigned new numbers to their soldiers, but this was obviously not applied everywhere. It was, however, adhered to for all new enlistments, and the assignment of specific number blocks to newly authorized units ensured that throughout the remainder of the war each soldier received a unique service number.

In keeping with the traditions adopted from the British Army, officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force were not assigned service numbers. In many cases, however, officers found in the Library and Archives Canada database will show a service number where the officer had previously served as a soldier and was commissioned from the ranks. When this is the case, a researcher should conduct subsequent searches of material by both the service number held as a soldier, and by name (with given names and, alternatively, with initials) as he would have been recorded after being commissioned.

This search result from the Personnel Records of the First World War (1914-1918) database shows officers' records without service numbers, and also one example (John Stanley Millett) where the officer served previously as a soldier, and his service record is also noted.

CEF service numbers are the primary identifier for Canadian soldiers of the Great War. To many soldiers of the day, and even today for researchers and collectors, the service number is the first clue to the story of that soldier's service in the war. That clue is inherent in the knowledge that most numbers were unique, and that the number also identifies the unit to which its number block was assigned for recruiting purposes.

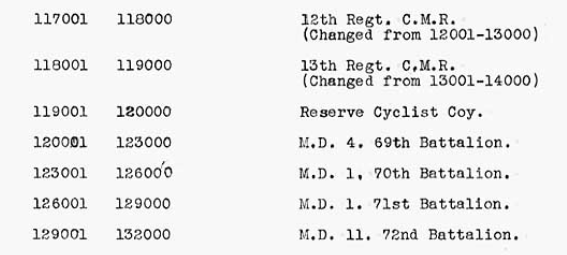

A summary document of the assigned blocks of service numbers is available at Library and Archives Canada and a set of the pages is linked below for download of the full set of pages.

Library and Archives Canada Regimental Number List (downloadable as 47 individual page files),

Or, for your convenience:

Courtesy of The Regimental Rogue, the complete document in one file CEF Service Numbers (pdf, 1.9 Mb).

An excerpt from the CEF service numbers document showing the number blocks assigned to units.

The service number reference document will provide, in addition to matching the recruiting units to their service number blocks, the Military District in which the unit was raised. This will provide a geographical area for further research into the recruiting activities of the unit.

Military Districts

| 1 | Western Ontario, east of Thunder Bay |

| 2 | Central Ontario |

| 3 | Eastern Ontario and Hull, P.Q. |

| 4 | Western Quebec |

| 5 | Eastern Quebec |

| 6 | Maritime Provinces |

| 10 | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Ontario west of Thunder Bay |

| 11 | British Columbia |

| 13 | Alberta |

This first piece of information, confirming the recruiting unit of the soldier being researched, helps to add to his immediately available story beyond his online attestation paper (see Part 1: Find your Man (or Woman)). For example, the reference Over The Top!: The Canadian Infantry in the First World War, offers the following information for the infantry battalions of the CEF:

- Unit name.

- Motto.

- The authorizing General Order number and date.

- Recruiting area.

- Mobilization area or headquarters.

- Service in:

- Canada.

- England.

- France (if any).

- Sailing date and ship on return to Canada if still a formed unit at war's end.

- Notes on the final disposition of the battalion (if absorbed into the reinforcement system or reassigned to other duties than line infantry).

- Officers commanding.

- Victoria Cross recipients, for fighting battalions.

- Battle Honours (if any).

An example of the information provided for Canadian Expeditionary Force infantry battalions in John F. Meek's Over The Top!: The Canadian Infantry in the First World War (pdf).

John F. Meek's Over The Top!: The Canadian Infantry in the First World War, though out of print and rare, can be found in pdf format through this link for private and non-commercial use, this repository has been established as an annex to the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group. Since the mediafire download site can be a frustrating experience due to download speeds and the number of steps to acquire each file, to simplify the process I have provided the full volume as a single pdf file (Caution, this file is 34 megabytes in size and may be a slow download depending on your internet connection).

Over The Top!: The Canadian Infantry in the First World War (pdf).

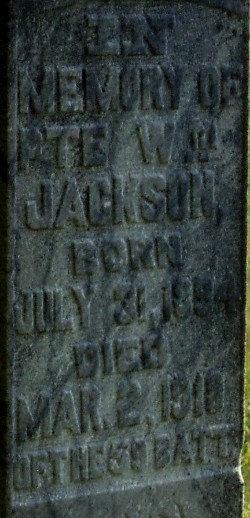

Recruiting Units and Front Line Service Units

The inscription on the gravestone for Private William Henry Jackson, who is buried in the Pioneer Cemetery in Coe Hill, Ontario. Although Private Jackson fought and was wounded as a soldier of The Royal Canadian Regiment and officially recorded a war casualty of that Regiment, he was buried by his family as a soldier of the unit into which he was recruited, the 59th Canadian Infantry Battalion.

When researching a Canadian soldier of the First World War, it is important to understand not only the significance of the recruiting unit which assigned the soldier one of its block of service numbers, but also that the soldier may not have served in that unit further than its arrival in England. In many cases, soldiers were known by their families to be recruited into the "local" battalion as it was raised for overseas service, their connection with his service overseas started with and was predominantly known by the number and naming of the unit with whom he marched away to war.

In some cases, soldiers who returned from overseas wounded may not have made it clear (or were physically incapable of doing so) to their families that they did not fight as a soldier of the unit with which they enlisted. Even though they fought under a different cap badge, they were known by family and friends as a soldier of the locally raised unit and, when some of those soldiers died of their wounds at home, they were buried as soldiers of that unit and not under the name of the unit with which they fought and were wounded. This happened in cases when a gravestone from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was not requested by the family, for that action would have often have required a confirmation of records before the stone was prepared.

This type of family burial of a soldier can lead to initial confusion in reconciling his units of service. Although this is not the only area where the oral narratives maintained by families, and local newspaper accounts such as obituaries, may conflict with research data, it is one that can cause some consternation and doubt over whether or not your research is on the right track.

To put it simply, it is important to know both the soldier's unit of enlistment, and the unit(s) he served with overseas. The experiences of the former unit will lead to his stories of recruitment, training and embarkation for overseas, the latter will be the unit of his actions on the battlefields and in the base camps of France and Flanders.

Confirming the soldier's unit of recruitment from his service number leads us to another document in the panoply of CEF records, the sailing list.

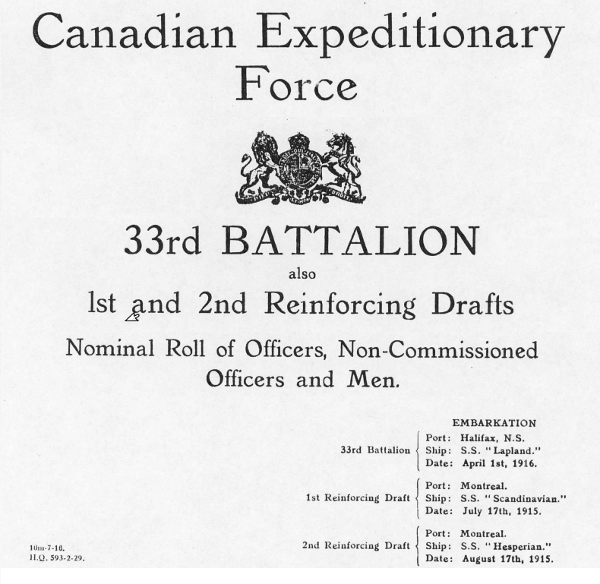

Unit Embarkation Rolls (Sailing Lists)

The applicable sailing list will confirm the unit in which your soldier left Canada for England on his way to the front in France and Flanders. The list cover will also confirm the date and location of embarkation and the ship on which he sailed.

The cover of the Embarkation Roll for the 33rd Canadian Infantry Battalion.

(This image has been reduced in size by eliminating white space normally seen between elements of the cover page.)

These CEF sailing lists are available through Library and Archives Canada and their detailed tables will provide much more detail than simply a listing of names, including:

- Regimental number.

- Rank on sailing.

- Name, surname and given names.

- Former corps, if the soldier had previously served in any military unit.

- Name of next of kin.

- Address of next of kin.

- Country of birth.

- Place and date the soldier was taken on strength of the CEF.

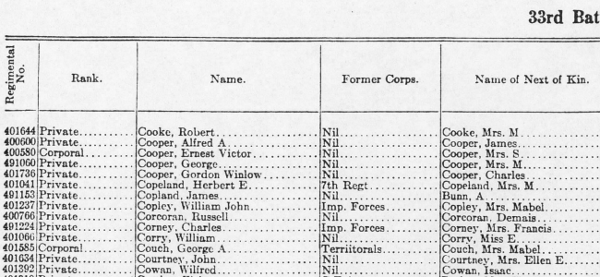

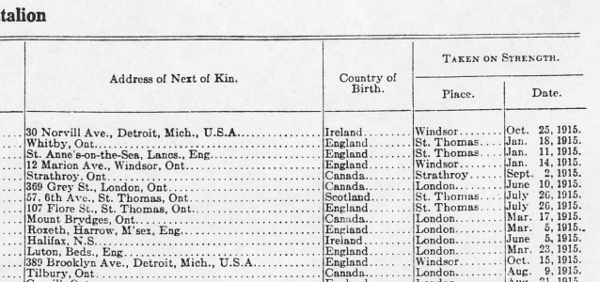

An extract from the Embarkation Roll for the 33rd Canadian Infantry Battalion showing the information contained in these rolls.

Note that the service numbers come from at least two different number blocks, "400501-402000" and 491051-491450", in this case both blocks were assigned to the 33rd Battalion for the renumbering of men recruited before the new numbering system was in place.

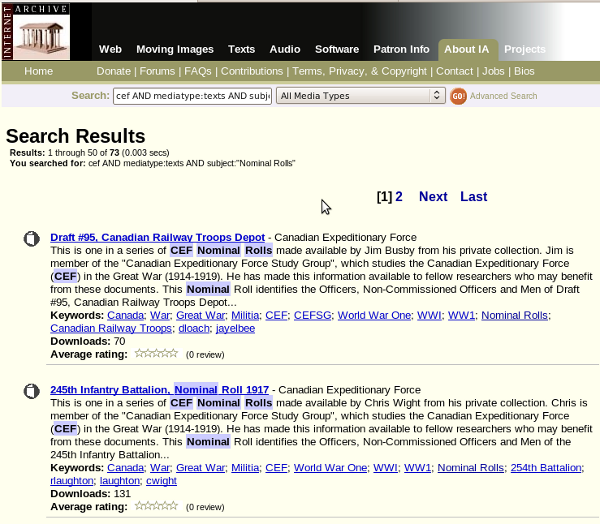

Some unit sailing lists have been added to the Internet Archive (Home) and a search for files tagged with "nominal roll" as an initial search parameter produces a number of results: cef AND mediatype:texts AND subject:"Nominal Rolls". Further searches, or requests on the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group, may produce the roll(s) you are looking for, otherwise seekg them through the Libary and Archives Canada.

Sample results from searching the Internet Archice for CEF nominal rolls.

When examining a sailing list or other nominal roll, keep in mind that each of these documents is a snapshot in time for the date they were created. CEF units were continuously being transformed as soldiers left and joined the unit for many reasons. The presence of a soldier on any roll does not imply that they spent any specific amount of time with the unit, only that they were on its nominal roll at the time that document was produced.

Nominal Rolls, Digging Deeper

The sailing list, as with any nominal roll your research uncovers, can be used for far more than just confirming the presence of your soldier in the unit at the time the list was created. Since the embarkation roll will include many of the soldiers who were recruited into your soldier's first unit (unless he's one of those few who moved between units before they left Canada), then the list can also be searched for any and all of the following:

- Soldiers with consecutive service numbers that may have joined with your soldier, compare next of kin addresses for those who may have been acquaintances through living near one another.

- Known other relatives and family friends whose service may not have previously been identified in family histories.

- Soldiers from the same street or neighbourhood as your soldier.

- Soldiers who may be mentioned in family stories and local histories.

- Soldiers matching names from school classes, sports teams or other activities your soldier engaged in before enlisting; or business associates in later life./li>

- Names matching those found in your soldier's letters or diaries.

Any and all of these may help to build a better picture of your soldier's service as a social experience, above and beyond the military adventure of serving as a soldier of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Conclusion

A soldier's service number is more than just an individual identifier, it can lead to the discovery of even more information to help develop the story of your soldier. As you progress with your research, watch for those occasional changes of service number that some soldiers experienced, and remember that officers did not receive service numbers, limiting this one aspect of research for them (but they will still appear in unit rolls, etc., for those avenues to further discoveries).

Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Introduction

- Part 1: Find your Man (or Woman)

- Part 2: The Service Record

- Part 3: Court Martial Records

- Part 4: War Diaries and Unit Histories

- Part 5: Casualties

- Part 6: Researching Honours and Awards

- Part 7: Deciphering Battlefield Location Information

- Part 8: More Mapping Information

- Part 9: Matching Battlefield Locations to the Modern Map

- Part 10: Service Numbers; More than meets the eye

- Part 11: Rank, no simple progression

- Part 12: Medals; Pip, Squeak, Wilfred and the whole gang

- Part 13: Evacuation to Hospital

- Part 14: The Wounded and Sick

- Part 15: Crime …

- Part 16: … and Punishment

- Part 17: Battalions and Brigades, Companies and Corps

- Part 18: Photo Forensics: Badges and Patches

- Part 19: Veterans Death Cards

- Part 20: The Vimy Pilgrims (1936)

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Vimy Memorial

- Dieppe Cemetery

- Perpetuation of CEF Units

- Researching Military Records

- Recommended Reading

- The Frontenac Times

- RCR Cap Badge (unique)

- Boer War Battles

- In Praise of Infantry

- Naval Toast of the Day

- Toasts in the Army (1956)

- Duties of the CSM and CQMS (1942)

- The "Man-in-the-Dark" Theory of Infantry Tactics and the "Expanding Torrent" System of Attack

- The Soldier's Pillar of Fire by Night; The Need for a Framework of Tactics (1921)

- Section Leading; A Guide for the Training of Non-Commissioned Officers as Commanders and Rifle Sections, 1928 (PDF)

- The Training of the Infantry Soldier (1929)

- Modern Infantry Discipline (1934)

- A Defence of Close-Order Drill (1934): A Reply To "Modern Infantry Discipline"

- Tactical Training in the British Army (1901)

- The Promotion and Examination of Army Officers (1903)

- Discipline and Personality (1925)

- The Necessity of Cultivating Brigade Spirit in Peace Time (1927)

- The Human Element In War (1927)

- The Human Element In Tanks (1927)

- Morale And Leadership (1929)

- The Sergeant-Major (1929)

- The Essence Of War (1930)

- Looks or Use? (1931)

- The Colours (1932)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- Origins of Some Military Terms (1935)

- Practical Examination; Promotion to Colonel N.P.A.M. (1936)

- Company Training (1937)

- Lament Of A Colonel's Lady (1938)

- Morale (1950)

- War Diaries—Good, Bad and Indifferent

- Catchwords – The Curse and the Cure (1953)

- Duelling in the Army

- Exercise DASH, A Jump Story (1954)

- The Man Who Wore Three Hats—DOUBLE ROLE

- Some Notes on Military Swords

- The Old Defence Quarterly (1960)

- Military History For All (1962)

- Notes for Visiting Generals (1963)

- Hints to General Staff Officers (1964)

- Notes for Young TEWTISTS (1966)

- THE P.B.I. (1970)

- Standing Orders for Army Brides (1973)

- The Time Safety Factor (1978)

- Raids (1933)

- Ludendorff on Clerking (1917)

- Pigeons in the Great War

- Canadian Officer Training Syllabus (1917)

- The Tragedy of the Last Bay (1927)

- The Trench Magazine (1928)

- Billets and Batman (1933)

- Some Notes on Shell Shock (1935)

- Wasted Time in Regimental Soldiering (1936)

- THE REGIMENT (1946)

- The Case for the Regimental System (1951)

- Regimental Tradition in the Infantry (1951)

- The Winter Clothing of British Troops in Canada, 1848-1849

- Notes On The Canadian Militia (1886)

- Re-Armament in the Dominions - Canada (1939)

- The Complete Kit of the Infantry Officer (1901)

- The Canadian Militia System (1901)

- The Infantry Militia Officer of To-day and His Problems (1926)

- Personality in Leadership (1934)

- British Regular Army in Canada

- Battle Honours (1957)

- Defence: The Great Canadian Fairy Tale (1972)

- The Pig (1986)

- Standing Orders for the Fortress of Halifax, N.S.; 1908

- Medals and Badges - Fakes and Copies

- Army Punishments Part 1 - • Part 2

• C.A.R.O. No. 6719 - Campaign Stars, Clasps, The Defence Medal and the War Medal 1939-45

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]