Murder at Wolseley Barracks (1908)

By: Captain Michael M. O'Leary, CD (The RCR)

Wolseley Barracks, named in 1894 after Field-Marshal Garnet Wolseley, was the Permanent Force infantry barracks in London, Ontario. Construction on the imposing brick building on the heights northeast of the town's centre began in 1886, and the barracks opened for instruction in 1888. Sitting on the low ridge of Carling Heights, Wolseley Barracks had been built to house the newly authorized "D" Company of the Infantry School Corps. The Corps, Canada's only regular force infantry troops, was established in 1883 and with the formation of the fourth company at London totaled no more than 400 officers and soldiers of all ranks.

By the early 1900s, the Infantry School Corps had been renamed three times, with these changes ceasing in 1901 when the Regiment was named "The Royal Canadian Regiment." In 1905, the Regiment expanded to include a regimental headquarters and six companies of infantry garrisoning Halifax where they replaced the last departing British Army garrison in Canada. Four separate companies still occupied barracks in St. Jean and Quebec City, Quebec, and London and Toronto, Ontario. In 1907, the St. Jean garrison was closed and the Fredericton station reopened. By this time, Wolseley Barracks was occupied by "K" Company of The Royal Canadian Regiment (The RCR).

Established initially to form schools of instruction for the Canadian Militia, this responsibility remained the important work of the separate company garrisons. The Regiment's troops at Halifax performed similar duties, but were also an integral part of the defensive garrison of Canada's vital east coast naval station.

Recruitment and retention in the Regiment was a challenge in the peaceful years between the South African (Boer) War and the First World War. Low pay, a monotonous existence for the soldiers, and the ease with which a man could disappear from the ranks once disaffected made for a sorry state of affairs. Regimental recruiting was poor enough that, local recruits being unobtainable in sufficient numbers, a draft of 154 men and boys, mostly ex-Manchester Regiment men, were taken on strength from Britain in early 1907 for the Halifax garrison.

The Regiment's garrisons all relied on fresh recruits who had not yet seen the often dreary life of peacetime soldiering. Complementing these were ex-soldiers, both Canadian and Imperial regulars, who were returning to the ranks after finding no other work to their liking, and transfers from local militia units as men decided to try their hand at full-time soldiering. Compounding the soldier's experience might be found the general distrust of uniformed soldiers among some of the population, especially where their daughters were concerned, and the requirement that a soldier was only permitted out of barracks in his uniform, forever branding him as "from the barracks."

But those attitudes towards soldiers were only one aspect of the soldiers' existence in a garrison of the period. While some families might look down on their daughter marrying a soldier, in other families it was a benefit to find a man with such steady employment, who might rise in the ranks and be a professional soldier and non-commissioned officer. Families in the Canadian provinces had also been known to see marriages to officers as respectable unions, though that may have changed somewhat with the departure of the British Army garrison battalion with their presumably titled and/or socially well-connected young officers. Full-time Canadian officers, on the other hand, lived on their Militia Department pay and could look forward to service in the few garrison towns that the Permanent Force occupied. In other areas of the shared life of community and garrison, soldiers could be found active in sports and cultural affairs; and the men of the Permanent Force garrisons and local militia units could have many personal bonds of friendship and shared interests.

The soldiers of the Wolseley Barracks garrison, uniformed when in the public eye, except perhaps at authorized sporting events, were expected by the military authorities to walk the tightrope of respectability. The choice, for the predominantly single soldiers, was drinking in the men's canteen, or drinking downtown in uniform. In either case, they could expect the ready arm of military justice to exact punishment in one form or another for any real, or sometimes only perceived, infraction. The close confines of the barracks, with men, non-commissioned officers, and officers all living and working in close proximity, left little room for secrets and the boundary between mutual respect and mutual disdain could be narrow. The stage was thus set for the building of esprit de corps, or the breeding of contempt, wherever they might flourish.

Alexander Moir

The night of Friday 17 April, 1908, Good Friday, was just one more night in the seemingly endless routine of life at Wolseley Barracks. Some men had turned in early, some were standing guards and duties, and some had donned their uniforms, passed inspection at the gate, and proceeded downtown. One of the latter was Private William Alexander Moir. Although he was enlisted and trained as an infantry soldier, Moir's daily employment at the barracks in 1908 was as the garrison doctor's groom.

Moir was an immigrant from Scotland and an ex-British Army soldier. Before coming to Canada he had served in the Gordon Highlanders, enlisting at Aberdeen for three years. It was reputed that Moir had served in South Africa and had also seen service on the North West Frontier of India.

Moir was about 25 years of age, with dark hair and eyes, five feet, eight and one-half inches tall, and with a muscular build. While sources don't provide the cause, he had a slightly disfigured right ear, a scarred right cheek, and was missing an inch of the first finger on his left hand. Described of being a man of volatile personality, Moir was known to carry a pistol off duty and reportedly pointed it at a comrade a few weeks before who had angered him while he was intoxicated.

Late that Friday evening, Moir was returning to the Barracks after spending the evening in town. His street car ride from the town centre towards Carling Heights was shared by Lieutenant Fred Douglas Snider, also of The RCR. The route they rode went north from the centre on Richmond Street, then eastward on a spur line along Oxford Street to the Adelaide Street intersection near the Barracks. Snider afterwards reported that Moir appeared sober at the time, but something must have piqued the young officer's curiosity. As a result he spoke to the duty sergeant, Colour-Sergeant Lloyd, and asked him to ascertain what medal ribbons were being worn by Moir.

This simple request, the answer to which does not appear to have been recorded, may have been the tipping point for Moir. On Moir's arrival at the barracks guardroom in the archway entrance to the barracks, Colour-Sergeant Lloyd confronted him. Shortly thereafter, Snider found Moir and Lloyd in the guardroom arguing. Lloyd declared that Moir would find himself in front of the Commanding Officer the next day for a charge of "improperly dressed in town." At that point, Moir would likely be on charge for insubordination as well. He tried to get clarification from Lieutenant Snider regarding the charges, but was directed to his quarters.

Lieutenant Fred Snider would serve briefly in The RCR. He was appointed to a lieutenancy on 14 March, 1906, and would be permitted to resign his commission in May of 1908. His resignation coming soon after the death of Color-Sergeant Lloyd, one might wonder if he might have considered himself an influence on Moir that night and bore the weight of a role in Lloyd's death.

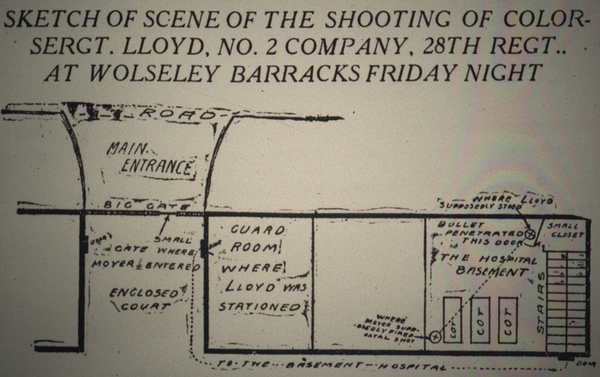

An angry Moir arrived in his room with an unknown amount of rage filling him after the ill treatment he perceived he had received from Snider and Lloyd. As the surgeon's groom, Moir did not live in one of the larger barrack rooms of the east wing of the "U" shaped Wolseley Barracks. Instead, he shared quarters in the basement of the north end of the west wing, under the barrack's hospital rooms. Moir's roommate was Private William Brady of the Army Medical Corps. Brady, the medical orderly, was serving an enlistment in the Permanent Army Medical Corps and would complete 2 years, 10 months and 21 days of service before his discharge. He would return to military service in 1914 as an infantry soldier in the 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion, rise to the rank of Sergeant, and be killed in action in late April, 1915.

Shots Fired

An angry Moir descended the stairs into the room under the hospital which he shared with the hospital orderly. Burning with the slight by Colour-Sergeant Lloyd and angered by the thought of being on orders parade, which would inevitably lead to some punishment, he was in no mood to go to bed. Waking Brady, Moir asked to borrow the second man's revolver, and with Brady's permission took the loaded weapon from his barrack box.

Moir briefly left the room and Brady heard shots before Moir returned. An inquisitive Brady was told to mind his own business and he did so as the safest course of action. The shots must have electrified those in the close confines of the barrack square that heard them. The unexpected sounds, recognizable to soldiers, would have demanded immediate action from the duty staff. Lieutenant Morris, the Orderly Officer, heard the shots and investigated, calling upon Sergeant Lloyd at the guardroom to accompany him.

Lieutenant George Charles Morris had been appointed to a Provisional Lieutenancy (supernumerary to establishment pending completion of training) in the 32nd Bruce Regiment on 20 June, 1907. His presence at Wolseley Barracks in April, 1908, was an an attached officer under training. Morris would resign his commission less than a year later, effective 15 February 1909.

In an era when soldiers in barracks might have their service weapons, personal weapons and ammunition for both at their bedspace, Moir was ideally situated to arm himself. Equipped with two handguns, Moir also picked up his service rifle. Strapping a bandolier of ammunition around his waist, he filled the pockets of trousers and his civilian overcoat, now worn over his uniform, with cartridges from the ammunition he kept in his quarters for rifle practice.

On hearing someone coming down the stairs, Moir picked up his rifle and loaded it, preparing to meet whoever it might be. Lloyd rounded the corner first, followed by Lieutenant George Morris. Morris had heard the first shots and was the one who identified them to Color Sergeant Lloyd. Now they were proceeding to confront the soldier who had disrupted the evening with gunfire.

In the basement room occupied by Moir and Brady, Lloyd found Moir facing him from across the room, rifle loaded and at the ready. Brady shouted a warning to Lloyd; "Look out, he has a rifle, loaded with ball ammunition." Lloyd ordered Moir to "Put that gun down!" When he failed to do so, Morris instructed Lloyd to "Take that gun away from him." Lloyd advanced, ignoring Moir's words as an idle threat when he declared "Hands up. Or I'll shoot!" Ignoring Moir's threat, Lloyd reached toward the rifle, and Moir pulled the trigger.i

As Lloyd fell to the floor, Moir threatened the unarmed Morris with the rifle next. Morris fled the room by the stairs, the only way out, and called for the guard to turn out. He was quickly followed up the stairs by an escaping Moir who disappeared into the night.

Moir's disappearance into the darkness after shooting Lloyd triggered a flurry of activity at the barracks. The turning out of the guard, posting of armed sentries, and a search for the fugitive soldier all kept the barracks' occupants busy into the night. The local police were notified and they reinforced the garrison with a squad of officers who immediately commenced a search of the vicinity of the barracks.

It was about midnight on Good Friday, 1907 and that barracks was now fully awake. Color-Sergeant Lloyd lay dying in the basement of Wolseley Hall, and William Moir was on the run from justice.

Sketch of Wolseley Barracks, west wing, published a few days after the murder and before the full details of the murder emerged. London Free Press, 20 Apr 1908.

Escape and Evasion

As the story spread through the town and rumours flew back and forth. The early news stories of Monday morning, 20 April, reported Moir as a volatile personality, one known to drink and who had been known to threaten others, including with his pistol. Dr. Belton, for whom he worked as a groom in the barracks, described Moir as a clever individual, and fairly well-educated. Moir had claimed to him to be a machinist by trade, who did his work in a satisfactory manner and minded his own business.

Called to the barracks immediately after the shooting, Doctor Cassius Wilkinson Belton, M.D., had been appointed to the position of surgeon-major with the Royal Regiment of Canadian Infantry (later The RCR) on 17 June, 1897, at the age of 36. His training as a military doctor would be advanced in 1898 when he attended a course of instruction at the Royal Army Medical Corps school at Aldershot, England. He would leave regimental service in 1904 on transfer to the newly designated Permanent Army Medical Corps and continue as the medical officer at Wolseley Barracks. He would be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the Permanent Army Medical Corps on 2 July, 1904, and attain the rank of Colonel in the Canadian Militia on 24 May 1916. In 19191, he would write "Pensions for the disabled soldier: Canadian Expeditionary Force."

It was initially unknown if Moir, armed and possibly deranged, had secreted himself somewhere in the barracks, or had escaped the garrison area. Fears of the former kept tensions high throughout the night. A newspaper reporter approaching the barracks with a friend after the story of the shooting had spread through the town was met at the gates of the barracks by armed guards. The level of danger and resulting tension was afterwards explained by one of the guards:

"If you had even raised your hand to point to any object in our direction, you would have surely received a bullet through your body. We were keyed up to such a point that in the darkness of the night, when objects could just be discerned in the moonlight, the fact of you raising your arm would have looked so suspicious that we would have not hesitated an instant in opening fire upon you young men."

Tensions decreased after the discovery of 40 rounds of ammunition near the garrison's eastern gate. This indication that Moir had escaped in that direction also provided an initial direction for the search to follow, and allowed everyone in the barracks to breathe a sigh of relief that he wasn't still hidden somewhere in the barracks.

Colour Sergeant Harry Lloyd

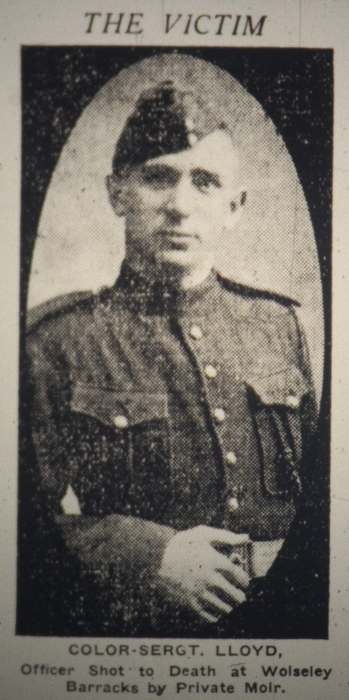

In the light of a new day, Moir was a fugitive, armed and on the run from military and police authorities. Behind him, his victim, Sergeant Harry Lloyd, lay dead. Surviving long enough to be moved to the barracks hospital in the rooms over the one where he was shot, Lloyd was awake for 20 minutes after the shooting but died within the hour. At the end, he knew that death awaited him. The bullet had traversed his body three times, penetrating the thumb of his outstretched left hand, his body, and finally his right arm before lodging in a door behind him.

With a fair complexion and a light moustache, the 25-year-old Lloyd probably didn't even look his years to the experienced campaigners in the barracks. He wasn't even supposed to be on duty that night. The roster had originally named Sergeant Arthur Youngman for the guard duty. But Youngman had asked Lloyd to trade duties with him and Lloyd's agreeable nature and willingness to do so placed him in the guardroom that fatal evening.

Colour-Sergeant Harry Lloyd. London Free Press, 20 Apr 1908.

Sergeant Arthur Youngman was an experienced old soldier. He had joined The RCR on 20 February, 1906, after having served 14 years with the British Army in the 2nd Battalion, The Manchester Regiment. With a birth date in 1870, we can safely assume that Youngman's British Army service spanned the years 1890 to 1895 (approximately). During this period the 2nd Manchesters served in India, the Middle East, the Channel Islands (Guernsey), on stations in the United Kingdom, and on campaign in South Africa. Serving in the Canadian Permanent Force throughout the period of the First World War, Youngman would attest for overseas service at Victoria, British Columbia, on 22 June 1918. From this and his declared residence at Esquimalt, he was likely employed at the regimental depot in Esquimalt during the war and only permitted to volunteer for overseas service when the restrictions on staff appointments were lifted late in the war. While serving with The RCR, Youngman would be awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal in 1914 and the Meritorious Service Medal in 1919.

A carpenter by civilian trade, Colour-Sergeant Harry Lloyd was a married militiaman from Number 2 Company of the 28th Perth Regiment located in Stratford, Perth County. He had previously taken courses at the barracks and was serving there again on attachment. Gentlemanly and friendly by nature, Harry Lloyd was popular and well-liked in the barracks. It was his sense of friendship and duty that kept him in the barracks when he might have been away, and his wife in Stratford had to receive the terrible news of his tragic death on duty.

Moir on the Run

By 9 o'clock the following evening, Saturday, 18 April, a party of police with one non-commissioned officer from the barracks were on Moir's trail. Plain clothed and heavily armed, the city police members were Detectives Thomas Nickle and Robert Egelton, and Sergeants Harry Down and Green, they were joined by Colour Sergeant Walter Gilmore from the barracks, a crack shot, in case his skills were needed. The men were accompanied in the early stages of their search by a reporter of the London Free Press.

With Detectives Nickle and Egelton engaged immediately, the police were putting their best men on the case. Thomas Nickle had joined the London Police Force in 1895 after serving as the Chief of East London. By the time of Lloyd's murder, Nickle had already built a reputation as a dogged hunter of fugitives with notable successes to his credit. Nickle, with Egelton, had arrested "Texas" Burdell in 1904 after a close range shoot-out that left Burdell's accomplice "Shorty Billy" Doyle dead. Nickle became one of the force's two detectives in 1892 and the Inspector of Detectives in 1920. Appointed Constable in 1897, Harry Down would become a detective and Sergeant of Detective before being the Chief of Police from 1930 to 1940.

The pursuers headed north east by hand car on the Grand Trunk railway line, towards Thorndale and St. Mary's. They were following up a report that Moir, still in his uniform and carrying a rifle, had approached the postmaster at the Grove just after 6 p.m. that evening. Postmaster Robinson had not yet heard of the incident in the barracks, and provided Moir with something to eat.

Heading further eastward, Moir reached the village of Wyton about 8:30 p.m. Here he tried to secure food and clothing from Albert Martin. His requests could not be fulfilled as the family's larder was empty and no clothes were available that might fit the fugitive.

These first two contacts gave the pursuers a direction to take in the early stages of their search for Moir. Albert Martin, afterwards, described Moir as perfectly calm, and noted that he no longer carried a rifle. Also at Wyton, Moir was seen by the postmaster there, Simon Blake, who was suspicious and refused to provide food or clothing.

Nearer Thorndale, Moir had another encounter. Meeting a small boy, he took the lad's cap, perhaps an attempt to start changing his appearance since his requests for clothing had come to naught. One more item came to light which confirmed Moir's direction of travel. In the early afternoon, two young boys, the sons of Dr. Hughes of Thorndale, found a rifle about a half-mile from that village on the road to Wyton. In addition to the reported sightings, this was solid evidence for the pursuers to set out on their manhunt.

Lloyd's Funeral

The funeral for Colour-Sergeant Harry Lloyd took place two days after the shooting, on Easter Sunday, 20 April, 1908. He was laid to rest in Avondale Cemetery with military honours. Citizens of the town lined the streets along which the funeral party proceeded. The regimental band of the 28th Perth Regiment led the procession to St James Church where the unit chaplain, Reverend W.T. Cluff, conducted the funeral service.

Sergeant-Major Keane of the 28th Regiment commanded the firing party which fired three volleys over the grave. Pallbearers came from the Sergeants' Mess of the 28th Regiment, and consisted of Quartermaster-Sergeant Lorne Smith, Pioneer Sergeant Fletcher, Colour-Sergeant Madill, Sergeant Bissett, Sergeant Wilson and Sergeant Doig.

Coincidentally, Stratford, Lloyd's home town and his final resting place, was directly in the path of the fugitive William Moir.

A Dangerous Fugitive

Moir's escape from the Barracks and apprehension of the anticipated pursuit bred much speculation. He was thought to be a man of volatile disposition who may have enjoyed his drink. Moir was also identified by a fellow soldier as a cordite eater. Apparently a popular practice in the South African War (1899-1902), men would remove the cartridges from bullets and eat the propellant powder. The described effects of this was contradictory, both like that of a strong stimulant and like morphine or similar drugs.

As a long serving soldier with Imperial Army experience in South Africa and on the north-west frontier of India, Moir was assumed to be an expert at living rough. This supposed skill, plus his heavily armed posture, created the expectations that he might be ready for pursuers, and willing to fight to the death for his chance at freedom. Moir's death, though desired by few, was not without consideration. The pursuers went forth with clear instructions to bring Moir in, dead or alive.

Battling the delay in getting information on sightings of Moir, real or suspected, and the challenges of traveling in the country, by hand car or carriage, the pursuers had their work laid out before them trying to close Moir's lead. The men searched locations where Moir might have laid up and rested, and on one occasion searched a barn to discover an unexpected occupant. An unidentified man from London, who had been tramping across country, laid up there to rest after drinking to excess. His besotted adventure may have ended in tragedy if the pursuers had been more aggressive in entering the barn in search of Moir.

The posse searched the country between Thorndale and St Mary's, coming up short of any solid leads as to Moir's whereabouts. In Thorndale, it was suspected, Moir and his pursuers nearly crossed paths. The posse rallied there late Sunday evening, using the services of the East Middlesex Telephone Company, in the offices under the management of Mr. James Stinson. Nearby was a barn owned by Mr. W.J. Evans wherein the evidence of a man having slept there was discovered. The evidence that it may have been Moir was that two blankets used by the interloper had been folded "military style" when he departed before the owner entered at 6:30 a.m.

Sightings of Moir, real or suspected, confirmed in the minds of his pursuers that he had fled to the north and east of London. News of the murder and Moir being at large had spread through the country and armed men greeted the official searchers at farms as they followed the leads they received. The discovery of Moir's discarded rifle, at least, reduced the threat of a long range engagement by Moir as well as confirmed his generally northward direction of travel.

After finding themselves no closer to capturing Moir by the end of Sunday, the first two days of searching came to an end and the searchers returned to the barracks, emptyhanded. In that time, no word of Moir had surfaced after the early sighting. The pursuers anticipated that Moir had gone to ground and remained hidden, or perhaps he had ended his own troubles with suicide. In balance to these theories, Moir had no way of knowing that Lloyd had died and, desperate as he may be, escape remained a very likely possibility for him.

The hunt for Moir continued, next following a sighting in the village of Tavistock. Moir was reported to have entered a local hotel by the fire escape, rifling drawers in search of clothes and being stymied by a locked closet before fleeing the scene. Identified by his general description and the cap he now wore, the search party had a new area to focus on and continued to canvas the area looking for Moir or any trace of his passing. By nightfall however, the members of the search party, which had been working in different areas around the Stratford, met at the Commercial Hotel in that town to compare notes of their fruitless efforts.

The search for Moir covered a growing area as sightings, real and rumoured, increased. Members of the search party ranged as far west as Goderich on the Lake Huron shore to St Jacob's, north of Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario. Reporters explained Moir's success at evading capture as proof of his soldierly skills learned in the British Army and developed in South Africa and on the Northwest Frontier of India. The papers also developed a sense of danger through descriptions of a desperate and armed man loose in the area and ready to kill to keep his freedom.

By Wednesday, 22 April, the searches were working in pairs and had divided the search area up into three sectors. Sergt. Downs and Sergt. Green covered the land from Stratford to Goderich, the area between Tavistock and Mitchell was in the hands of P.C. Bolton and Color-Sergt. Gilmore, and Detectives Nickle and Egelton worked the territory around Berlin and St. Jacobs. Following up a hundred clues, the search party remained confident they were closing a noose on the fleeing man. But the clues were thin and sometimes completely fictional. The last confirmed sighting of Moir was Sunday morning when he approached a man named Robinson at his farmhouse near St Mary's and asked for food. By the end of the week, sightings of Moir seemed to localize around St Jacob's, Ingersoll, and Woodstock, drawing the search area to the region east of London.

On Friday 24 April, while the search for Moir continued, a Coroner's Inquest into the death of Color-Sergeant Lloyd was being held in London. The seventeen membersiii of the jury heard evidence from witnesses to Moir's actions on the night of the murder.

The inquest jury heard from Lieut. Morris, who had been behind Lloyd when the fatal shot was fired. Doctor Belton read his post-mortem examination to the jury, describing Lloyd's wounds and his death by blood loss, primarily from the liver, and shock. Sergeant James Carter described Moir's arrival at the barracks that night, and how he was met by Lloyd who warned him for company orders the following day. Carter informed the jury that the warning had incensed Moir, who returned to the guardroom to try and discover who had placed him on report, which he was told he would learn the following day.

Private Brady, who had occupied the room under the hospital with Moir for two months, described how Moir had come into the room and armed himself with pistols, rifle and ammunition. Brady detailed the shooting and also noted Moir's volatile nature and the threats he had made toward Color-Sergeant Gilmore over perceived slights during the preceding months. Brady also shared with the jury that the amount of ammunition available to Moir was unusual but that it had been in the barracks room for over eight months. The inquest jury had little difficulty in returning with a verdict of willful murder.

A Fruitless Chase Continues

By Saturday, the 25th of April, a week after the night of the murder, the search party pondered a trail grown cold. Having followed rumours all over the surrounding countryside, no further solid leads to Moir's whereabouts had arisen. Every unfamiliar face, or person dressed strangely, or asking for directions, was cause for a new suspicion that Moir was about the country. Each rumour was investigated, but to no avail. The prevailing suspicion was that Moir had gone to ground, and was laying low in the area between the communities of Heidelberg, St. Jacob's (where he was last reported with any confidence), and Guelph.

It was believed that Moir had some friends in that district, who might be assisting his concealment from authority. The search party remained confident that Moir would be found, while admitting that chases through open country could often be long ones. It was also known that Moir received army reserve pay from England on a monthly basis, and any attempt to acquire these funds would be a potential opportunity to narrow the search and secure his capture. Color-Sergeant Gilmore, having known Moir at the Barracks, described him as a braggart to his fellow searchers, and suspected that his habit of talking too much might also lead to his identification and capture.

Throughout the week since the murder, the hunt for Moir ranged over the country around London. The search area was shown by one local paper as follows:

- Saturday – From London to Thorndale

- Sunday – From Thorndale to Wyton Station

- Monday – From Wyton Station to St. Mary's

- Tuesday – From Stratford to St. Mary's, Tavistock, Stratford to St. Mary's, Stratford to Ailsa Craig

- Wednesday – Stratford to Harmony, Stratford to Seaforth, Goderich, Mitchell, Goderich, Centralia and St. Mary's

- Thursday – From St. Jacob to all surrounding villages

- Friday – From Guelph to surrounding points.iv

Working in pairs, the searchers had covered as much ground personally as humanly possible. Trains, handcars, and horses provided the necessary motive power, but the diligence of the searchers was met by a trail grown cold.

The Ammunition Question

A lingering question in the military community following the reporting on the coroner's inquest was concerning the ready availability of ammunition in the barracks. The London Free Press, publishing a column titled "Military Minutes," raised this issue in two paragraphs by pseudonymous author "Major R.E.D. Tape":

"The sad tragedy which occurred at Wolseley Barracks last Friday night brings most forcibly to our notice a question which has received far too little attention in the past. This question is the accounting of ammunition. Private Moir should not have had ammunition in his possession. Where he got it we do not know, but at any rate someone, charged with the custody of ammunition, has been careless, and by his carelessness has aided a man to commit a most cold-blooded murder.

"We are quite sure that this same carelessness exists to a very large extent among the rifle associations and militia corps of the country. A considerable portion of the ammunition issued to some of them is never properly accounted for, and we may safely say that it is not expended in the manner intended. It is scattered across the country in the hands of persons who should not have it. To prevent such in the future, the militia authorities should get busy at once."

A Reward is Offered

The Dominion Government, in response to the lack of fresh clue which could put the reassembled search party back on Moir's trail, offered a reward in early May, a full three weeks after the murder. $500 was offered for the arrest of Moir, or the provision of information leading to his arrest. In the normal manner of such affairs, the notice would be sent to every post office in the country, in hopes of stimulating fresh clues and a solid lead.

Three days. That's all it took before someone was claiming entitlement to the reward.

At 6 p.m., Saturday the 9th of May, 1908. Moir was taken into custody at Elora, Ontario, by Chief Constable Farrell of Arthur and Constable Coughlin of Wellington. Acting on a tip Farrell received, and later claiming not have known of the reward, the constables descended on the farm where they expected to find Moir. At the farm of David Robb, who had hired Moir to pick rocks, the two constables employed a ruse about buying horses to get onto the farm where Moir was working and to get close to their target. And get close they did, in a knock-down, drag-out fight with a man determined not to be taken into custody. The two constables subdued Moir after a vicious fight in the farm's stable, and succeeded in getting cuffs on him to make the arrest. Moir, it turns out, had been working on the farm for a wage of $22 per month since the 22nd of April, starting there only five days after the shooting and while the search party was still chasing rumours of his presence elsewhere. After the capture of Moir, the constables reported that he had been worked into a rage by the fight, and left in a mood they felt would have ended in further murders if Moir had been armed at that time.

In custody and held first at Elora, Moir was his reportedly talkative self. He described his route from London to Elora by identifying where he spent each night:

"The first point he touched, taking his own statement as the truth, was likely The Grove, where he stayed on Saturday, the day after the tragedy. Saturday night he slept at a barn further on. On Tuesday he spent the night in a Stratford hotel. On Wednesday he was in Elora. These are the only places he claims to have stopped."

Moir also admitted that his most grievous error was admitting to people that he was, in fact, Moir. In London, Police Chief W.T.T. Williams confirmed Moir's capture to the London Free Press, and mush praise was directed at the constables who effected it. The offer of the reward and the resulting issue of 7000 circulars across the country kept the case in the public eye, providing the necessary information and inventive for Farrell and Coughlin to act when they heard of Moir's likely location.

Even as the Elora constables were taking action, word of Moir's location had also reached the ears of Constable Blacklock, of Elora, Ontario. Working with information from Charles Robb, Blacklock first sought reinforcement from the Guelph police, but by the time the party of Guelph Chief of Police Randall, Constables Greenaway and Blacklock, and Charles Robb reached the farm, Moir was already in custody.

With Moir secure in the lockup in Elora, word of his capture was sent to the London police. Shortly after Moir's capture was confirmed, Detective Thomas Nickle set out from London to bring Moir back to the city.

James Robb, the brother who owned the farm where Moir was captured, afterwards told his story of how Moir came to be working on his farm to the London Free Press by telephone. On the night of 22 April, Moir, looking rough and asking for work, had arrived at the farm when only Robb's wife was at home. The family being unaware of the tragedy in London at the time, or that an escaped murderer was on the loose in the area, she took him in for a meal and when the farmer arrived, and agreement was made to employ Moir for $22 per month, which might later increase to $25 if he stayed on.

The farm only received a Toronto paper, and as yet had not seen the story of Color-Sergeant Lloyd's murder. When a copy of an Elora paper came to the house, Moir secretly cut out a section which included a description of himself in an effort to maintain secrecy a little longer. He also switched caps, taking one from the farmhouse, to alter his appearance once again when he was sent on an errand to a nearby town. Unfortunately for Moir, a toothache was almost his undoing. Complaining of pain, he was sent to see Dr. Wallace in Alma, who treated him, but also recognized his patient and later shared this knowledge with James Robb.

Moir had been working on the farm for eight or nine days before his identify became known to the Robb family. They had also determined that he was armed much of the time and did not raise the alarm for their own safety. By the 9th of May, Saturday, the Robbs were prepared to enable the capture of Moir at their farm. Charles Robb went to Elora and informed Constable Blacklock, which led to the late arrival of Blacklock's party to find Moir already in custody.

James himself had been met by constables Farrell and Coughlin as they approached the farm where Moir worked. He pointed out the barn where Moir would be found and warned them that Moir would be a dangerous adversary. Despite their roles in the affair, James Robb admitted that the family did not expect any share in the reward.

Held in the lockup at Arthur, Moir was visited by and talked to a number of people. He claimed to have known the details of his act and the progress of the search, but not at first. He claimed that his first indication that he had done something wrong was when he woke up in a barn six miles from London, armed with his rifle, but lacking any clear memory of the night's activities. He had worked his way eastward until, while mingling in the crowd at a horse show in Elora, heard that the Robb's were looking to hire a farm hand. Moir's last public visitor was a Scotsman, who claimed to also be a veteran of the South African War, and whose conversation reminded Moir of home, and possibly of his mother, causing him to become agitated. After this, only the police officers spoke with Moir.

Return to London

Moir's return to the city was much anticipated. Word had spread of his capture and the train arriving on the morning of the 11th was met by a crowd of "fully 500 morbid curiosity seekers." They were disappointed at discovering that Moir was not on that train and that he was not expected to arrive before the night train at 11:30 p.m. Beginning with the murder and manhunt, Moir's incarceration and trial would continue to be a highlight of London's news for 1908. Speculation about whether Moir might plead insanity and whether his more likely fate was the hangman's noose or incarceration in an asylum immediately became fodder for friends and strangers to discuss.

As a well behaved and articulate prisoner, Moir generated some feelings of sympathy among the interested public. He confessed to interviewers an intent to flee far from the scene after the shooting, but happenstance found him working at the Robb's farm. He also professed a degree of remorse and even admitted to have considered returning to London to surrender himself. He was now willing to accept what fate would now deliver him, but this may as well have been a response to the situation he was now in as he awaited trial.

In London, Moir would be represented by a lawyer from the town of Arthur, Mr. M. Wilkins. Efforts were immediately made to secure the representation of Mr. Edmund Meredith, K.C., of London as counsel for the defence.

Also standing for Moir was Rev. W.T. Richardson, a Presbyterian minister who described Moir as an honest man who attended church regularly. He noted to the papers that Moir had family; a mother, brother, and sister at Hawick in Scotland, and that his grandfather was also still alive.

Access by the press to prisoners and anyone else involved in case such as Moir's are evident in the newspaper reporting of the era. The London Free Press offered some clues as to Moir's mental state with the following lines:

"At first, when I realized what I had done, the impulse was strong within me to return to London and give myself up. I wanted to rid myself of the whole thing, even if it cost me my life. But I hadn't the pluck to do it. Then I made up my mind to get away, if I could."

"No, I do not ask for any sympathy now," he said, "All I ask for is a fair trial. If I am guilty of this thing I must take the consequences. But I feel that I was not responsible."

Moir denies absolutely that he ever ate cordite. He says it was drink entirely that is responsible for his present position.

The face of the young man wears a saddened expression. He is undoubtedly aware of the seriousness of his position."

Moir stepped off the Canadian Pacific railway train at 11;30 p.m. on the evening of May 11, 1908. He had been escorted on the 153-mile journey by Detective Nickle and met at the London station by Detective Egelton and other officers. Moir spent his first night in London at the Carling Street police station, although he would soon be moved to the county jail in London as he passed into the hands of the court system.

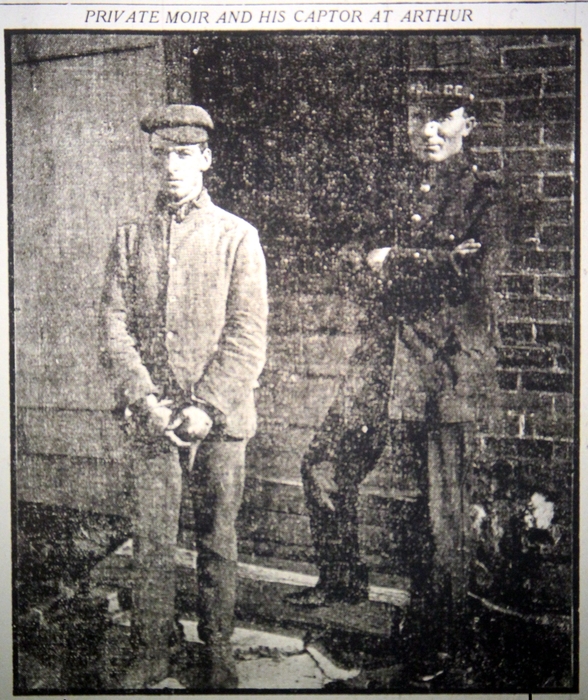

William Alexander Moir and Constable Farrel of Arthur, at the jail in Arthur, Ont., following Moir’s capture. The Evening Free Press, London, Ont., 12 May 1908.

Trial Preliminaries

William Alexander Moir made his first court appearance on the morning of 12 May. This appearance was a formality, during which Moir would be remanded for a later preliminary hearing, in front of Police Magistrate Love. In only five minutes, Moir was informed that he was to be charged with the murder of Henry Lloyd and the preliminary hearing was set for that Friday, the 15th of May.

Present in the courtroom for that first appearance were Dr. Belton, the surgeon at the barracks, and also Sergeant Gilmore, who had been a member of the party who first pursued Moir. Gilmore informed reporters that Moir had been struck from the rolls of his Regiment as a deserter, effective the day after the murder. He also spoke briefly to Moir, making arrangement to send Moir's personal effects to the prison on his behalf.

Perhaps it was Moir's model behavior since his arrest, or his suggestions at being repentant, or the details of his life that were shared, but public sentiment somehow started to swing in favour of the man first hunted and feared as a dangerous killer on the loose. It began in Arthur where he was held between his arrest and being escorted to London by Detective Nickle. Moir had a new suit for his trip to London, courtesy of the Robbs paying him money he was due for his labours and the contributions of other townspeople. Supporting this evolving opinion of Moir, the papers began to report that Moir did not appear to be the killer that had been described during ethe manhunt.

As a result of the impression Moir had made upon the people of Arthur, a fund was begun to collect funds to support him. Among the named subscribers were the following prominent community members:

- Rev. Father Doherty, pastor of St. John's Church,

- Rev. W.G. Richardson, pastor of St. Andrew's Church,

- J.A. McGill, manager of Trader's Bank,

- M.J. Brown, proprietor of the Arlington Hotel,

- George A. Shoner, jeweler,

- Rev. Mr. Russell, pastor of the Latter Day Saints' Church, and

- Reeve Colwill

Moir's repentant attitude and his polite explanations worked on the hearts and minds of many who met him. His claims that he remembered nothing of the event, and that he was unaware of the fate of Sergeant Lloyd until days later, opened the door to considerations that he might not have been fully responsible for his actions. Some of his newfound friends and supporters were willing to believe that he may not be criminally guilty of the murder.

At 3 p.m., on Friday April 15th, 1908, William Alexander Moir appeared again in court before Police Magistrate Love, this time for the commencement of his preliminary hearing. He was formally charged with the murder of Sergeant Henry Lloyd by Sergeant Walter J. Gilmore, of Wolseley Barracks. Mr. Meredith, K.C., was prepared to appear for Moir, but it was anticipated that he would not argue against evidence. As Moir's counsel, Meredith's priority at this time was to ensure a fair process and to eliminate inadmissible evidence such as hearsay. Despite the great degree of public interest in the case, police limited public access to the courtroom to a few dozen spectators.

Meredith's cross-examination of witnesses focused on the possibility that Moir was "crazy drunk" at the time of the shooting. Unfortunately for Moir's case, none of the witnesses would admit to that, although some came close. They were, however, ready to describe Moir as being in a "sour mood" on the evening of the murder.

Moir was a well-behaved prisoner in the county goal. This being reported no doubt added to the readiness of some citizens to feel sympathy towards his case. The jailers, guarding against then possibility, took every precaution to prevent the likelihood of escape. The London jail had been beaten before, when a notorious prisoner nicknamed "Texas" had escaped some years before.

As a sidebar to the approaching trial, there was discussion and debate regarding who would be entitled to claim the reward for Moir's identification and capture. Notices for the reward had specific that it would be paid in return for "the capture, or information leading to the capture" of the fugitive. Among the parties claiming entitlement to the offered $500 were the Robb brothers, P.J. Ferrell of Wellington, and Mr. Draper. It would, however, be some months before the recipient would be identified following the submission of affidavits by claimants establishing their roles in Moir's capture.

Moir's preliminary trial covered the same ground and evidence as the inquest into the murder. Crown Attorney McKillop acted on behalf of the crown and the cross-examination of witnesses was conducted by Meredith.

All of the witnesses called during that session were from the barracks. Meredith repeatedly sought to establish grounds for the defence theory that Moir was "crazy drunk" but none of the witnesses supported that assertion. Lieutenant Morris was questioned by Meredith to establish if he thought that Lloyd's own action in grabbing for the rifle may have contributed to the pulling of the trigger, but he never clearly made such an admission.

Fred Snider, formerly a Lieutenant who had served for two years at Wolseley Barrack and who had since left that service, was the first witness called to the stand. He described seeing Moir, along with Sergeant Carter of the 7th Fusiliers, on the streetcar about 11:45 p.m. on the night of the shooting, and that both of them had been drinking.

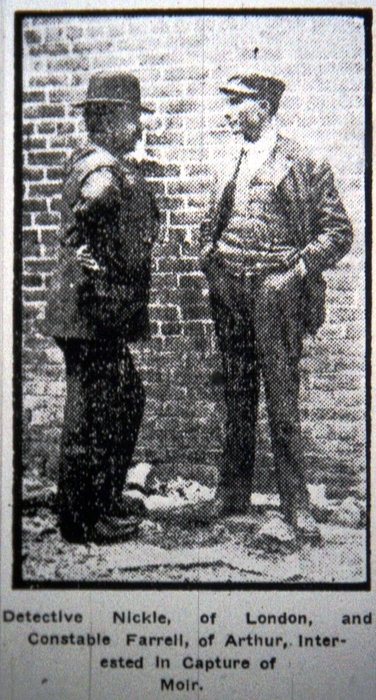

Detective Nickle, of the London Police, and Constable Farrell, of Arthur. The Evening Free Press, London, Ont., 12 May 1908.

Having left the streetcar himself to return to the barracks, Snider spoke to Sergeant Lloyd on entering the barracks and after seeing Lloyd speaking to Moir, also had an exchange with the accused man. Moir had approached Snider to ask why he should be "up for company office" in the morning, i.e., to be charged for a minor crime. Snider had told Moir that he would find out in the morning and stated that Moir at the time did not appear intoxicated. He was unaware that the conversation he witnessed between Lloyd and Moir had been a heated exchange. Ending his own conversation with Moir, who he described as showing an excited tone and manner, Snider had ordered him to his quarters.

Snider confirmed that he had known Moir throughout his two years at the barracks. He claimed not to know if Moir was addicted to drink. Admitting that he knew Moir to be under the influence of liquor on the night of the murder, Snider's remarks led Mr. Meredith into an interesting exchange to attempt to define "drunkenness."

Snider - "A man is drunk when he is incapable of doing his duty." Meredith - "If he could walk straight and talk straight would he be drunk?" Snider - "Not necessarily." Meredith - "If he could not perform his duty would he be drunk?" Snider - "Yes, sir." Meredith - "There are no degrees of drunkenness with you?" Snider - "No, sir."

Sergeant Carter, of the 7th Regiment, Fusiliers, an infantry unit of Militia headquartered in London, was next called to the stand. Carter had been on the streetcar with Moir, the two having been seen together by Lieutenant Snider.

Carter, a city resident at 167 Wortley Road in London's south end, was returning to the barracks and had met with Moir at the corner of Dundas and Richmond streets. Together they went on the street car toward the intersection of Oxford and Adelaide streets, the stop closest to Wolseley Barracks. Carter acknowledged that Lieut. Snider occupied the same car.

Carter accompanied Moir into the barracks at 11:45 p.m. He described to the court that Sergeant Lloyd pulled Moir aside to speak with him, and informed him that he would be up for company orders the next morning. Moir demanded to know the reason, and that not being provided, Moir left the guardroom and approached Lieut. Snider to speak with him. As Moir began speaking with Snider, Carter continued to his own barrack room and was not party to the exchange between Moir and Snider. Shortly after getting to his room, Carter stated he heard a shot which to him appeared to come from the barrack square. He went to his window, from which he saw two figures who he could not identify crossing the square at a run.

Asserting himself to be a teetotaler, Carter hedged under cross-examination in confirming if Moir had been drinking. He did allow that Moir had been in a nasty mood when speaking with Sergeant Lloyd at the guardroom, challenging him to admit that it was Snider who had placed him on company orders.

Carter had remained inside after the first shot, but redressed and came back out of his room after hearing the second shot of the night. He refused to rise to Meredith's line of questioning that he had remained inside after the first shot out of fear. On being examined about Moir's character, Carter stated that he had not known the accused well but was on good terms with him.

Next called to the stand was Doctor Belton, the surgeon at Wolseley Barracks. Belton had known Lloyd, and had made a post-mortem examination of his body after the shooting. He confirmed that the cause of death was the bullet that passed through Lloyd's chest and pointed out for Meredith the path the bullet had taken. Meredith, likely in pursuit of his theory that Moir had been under the influence of something, next queried Belton on the use of cordite by soldiers. Belton acknowledge that cordite could act upon the brain as a powerful and temporary stimulant.

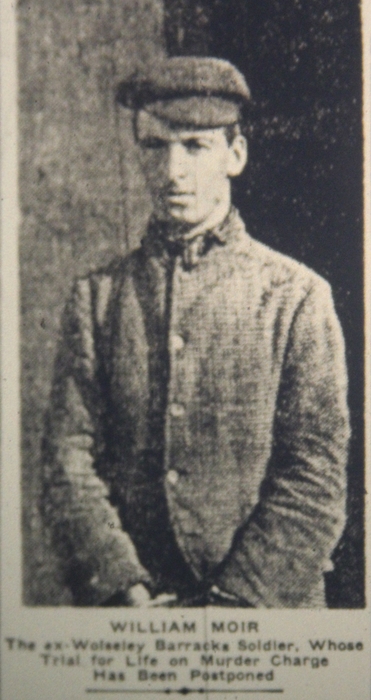

William Alexander Moir. The Evening Free Press, London, Ont., 6 Oct 1908.

Cordite was a nitro-glycerine based propellant used in rifle cartridges. While a single cartridge may contain 60 strands, it only took a few to have an effect on a user. Major J.W. Jennings, D.S.O., writing in a 1903 Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps article titled "Cordite Eating and Cordite-Eaters," stated the following points based on his observation of soldiers using cordite during the South African War:

- "Cordite, when taken in "strand" form, rapidly produces a violent splitting headache in the temporal and occipital regions, the headache continuing all day."

- "Cordite has a sweet, pleasant, pungent taste, and is only slightly soluble in the mouth. Its physiological action is similar to, but slower than, amyl nitrite, viz., throbbing headache, flushing of the face, visible carotid pulsation, giddiness and disordered action of the heart, &c."

- "When taken with beer or tea (five to ten strands), cordite appears to produce heavy sleep, followed by a stupor lasting approximately five to twelve hours. The larger the quantity taken the longer the sleep."

- "Taken in solution, as with tea, cordite appears to produce an almost immediate exhilarating effect, inciting to almost demoniacal actions. … This condition lasts perhaps two or three hours, when the effect seems to die away and sleep overcomes them, or if there should be an unexpected cessation of the excitement (as upon being reprimanded for making such a noise) they all seem to be overcome by a stern sense of discipline, roll over and go to sleep."

As a veteran of the South African campaign, it is not outside the realm of possibility that Moir had experience with cordite eating, either personally or through the observation of others. It may have been one of his own habits, but it never confirmed during the trial.

Sergeant Herbert Braddon, of Wolseley Barracks, was next examined. Providing a series of glimpses of the evening, he described seeing Lloyd tell Moir that he was for "office," and an angry Moir's return to the guardroom to demand to know who had crimed him. Braddon saw Lloyd enter the guardroom to grab his belt and bayonet, a clear indication that he was setting off to perform a required duty. He next saw Lloyd on the floor of the hospital after the shooting.

Private Gordon Hymmen, asleep in the guardroom, was wakened by the exchange between Lloyd and Moir. He repeated earlier testimony about the two men, confirming both that Moir was excited but not noticeably under the influence of drink. He confirmed that he had never seen Moir drunk, or behaving in that fashion before.

Hymmen would still be serving in The RCR at the outbreak of the First World War. He would serve with the Regiment in Bermuda (1914-15), and proceed overseas to cross into France in November, 1915. Hymmen would serve five months in and out of front line trenches before being evacuated to England sick. He would eventually be declared medically unfit for further service and return to Canada to be discharged on 16 February, 1918.

Private William Bedford Brady had the unique position of sharing a room with Moir under the hospital in the west wing of Wolseley Hall. He had gone to bed at 9:30 on the evening of the murder and was awoken shortly before midnight by Moir asking to borrow his revolver. Giving permission and moving his watch from his barrack box for Moir to get the revolver from his pocket, Brady let Moir take the loaded .32 calibre pistol and leave the room. Soon after, Brady heard a shot, the first one that others had heard from the barrack square.

Returning to the room, Moir stripped off his coat and began to arm himself more fully. Starting with a cartridge belt and adding more cartridges to his pants pockets. Brady asked Moir his intention and was bluntly advised that he should remain quiet. About this time footsteps were heard on the stairs leading down to the basement barrack room. Moir grabbed up a rifle from Private Carvis' bed space and loaded it as he waited to see who would next enter the room.

Brady, finding his voice, shouted "Hello! Hello! Hello! Look out, he got a loaded rifle."

Sergeant Lloyd, followed by Lieutenant Morris, entered the room to confront Moir. Moir was ready for them, standing between the beds at the side of the room opposite the door, with the loaded rifle at his hip. Moir was ordered to drop the rifle and Lloyd stepped forward. In an instant the rifle fired, undoubtedly loud in that enclosed basement room, and Lloyd dropped to the floor. At a distance stated by Brady of four feet, Lloyd would not have been able to grab the rifle before it discharged.

Moir, his soldierly habits probably working through any shock of his actions, ejected the spent casing and loaded a new cartridge with practiced movements. Turning the rifle toward the unarmed Morris, he saw the officer duck around the corner and climb the stairs to get out of the possible line of fire on Moir's only escape route. Moir followed Morris up the stairs, and disappeared into the night. Back in the basement, Brady tried to assist Lloyd but found that any attempted movement was protested against by the dying man.

Meredith continued examining Brady about the weapons and ammunition in the barrack room. Brady admitted to having the loaded pistol, even though he believed he wasn't supposed to. He was unsure if the rifle Moir picked up had already been loaded, but also that he had 200 rounds of ammunition in his bedside cupboard. This also was against the rules of the time, and Moir had known the ammunition was there, having received permission from Brady to use it himself on range days.

Brady stated that Moir also knew of his pistol, having borrowed it before. He had never asked Moir what he wanted the weapon for but did confirm it had never been discharged at such times. Brady's final remarks in response to Meredith's questioning was to admit that he hadn't felt frightened because the incident happened to quickly to experience that emotion.

Lieutenant George Charles Morris described hearing the first shot, from Brady's revolver, and meeting Sergeant Lloyd at the guardroom from where the headed from Moir's barrack room. They entered to find Moir armed and threatening them with the loaded rifle. Morris ordered Lloyd to disarm Moir, hardly expecting his to use the weapon, and was trapped on Moir's escape route when Lloyd fell to the floor. Morris took his only course of action and escaped up the stairs to call out the guard. In response to Meredith attempting to advance his theory that Lloyd's actions may have contributed to the shot being fired, Morris could not confirm if Lloyd had touched the rifle in Moir's hands before the shot.

The evidence given at the preliminary hearing was more than sufficient for the magistrate. On 19 May, delayed by the time necessary to transcribe the preliminary hearing testimonies, Moir was committed to be tried for the murder of Color-Sergeant Lloyd. Moir would return to his prison cell to await trial in September, four months away.

Rumours of the possibility of the trial being avoided by the accused's suicide abounded. In prison, he was closely watched to avoid this possibility even as the authorities claimed that the rumours were untrue. They appeared to believe their own opinion in the matter, as no special guard on Moir was added to the usual staffing of the jail.

About this time Moir had a visitor, a young lady from Hawick, Scotland, who was described as unsympathetic towards Moir. A fellow Scot, she only wished to discover how Moir himself had come to Canada and offered to communicate with his family back home on his behalf. She left disappointed, with a taciturn Moir making no requests for her to action.

Waiting for Trial

Although Moir's trial was initially predicted for September, he would not return to court until the early days of October 1908. Over the summer he was described as model prisoner. Moir was allowed to mingle with other inmates in the prison yard and known to talk about his case, albeit reluctantly, with the guards, all of whom remained under strict orders not to discuss his situation outside the county jail.

By mid-September, the counsel who would represent Moir at trial were confirmed. Mr. Meredith, who had been with Moir at the preliminary hearing, would be joined by Mr. M. Wilkins, an attorney from Arthur, Ontario. Together these men would make the case to keep Moir from being hanged, the logical conclusion of that presented objective being that a verdict of other than guilty for the act of murder was unlikely.

The question of the reward also came back to the public's attention in September. During the summer a government official from Ottawa, following up the affidavits, was in Arthur gathering further evidence in regard to the various claims on the reward money. A decision was announced in the London Free Press on 21 September, confirming that the reward would be given to P.J. Farrell, the Chief Constable at Arthur, for his role in Moir's apprehension. Farrell, in turn, divided the reward equally with Draper, the stage driver who had informed him of Moir's whereabouts.

In the final days of September, 1908, the date for Moir's trial was finally set and announced. On 5 October, Moir would be placed on trial for the murder of Colour-Sergeant Harry Lloyd.

Despite being described as having few friends in the country and that his legal defence would be provided by the Government, Moir's case continued to excite the public interest. Donations were received by three subscription accounts set up to support Moir's legal defence. Contributors desired only that Moir receive a fair chance at saving his life, ensuring a minimal sentence if guilty, or even seeing him free again. Rumours established that the most likely defence was one of temporary insanity, but these were countered by the unattributed opinion from the barracks that Lloyd's murder was an act in cold blood by Moir, undeserving of leniency. The disparity of opinion set the stage for a dramatic trial, with Moir's life held in the balance.

In the days before the trial commencing, with interest in the case reawakened, it was revealed that Moir had prepared the barn at the Robb farm for a fight. It appeared that Moir had prepared the building for a last stand, with loop-holed walls to allow him to engage officers approaching from any side. It was supposed that Moir's experience as a soldier contributed to the expert preparations described for the building's defence.

The Fall Assizes

At 2 p.m. on Tuesday, 5 October, 1908, Chancellor Sir John A. Boyd entered a courtroom in London Ontario and commenced the fall assizes of 1908. It was here that Private William Moir would be tried for the murder of Color-Sergeant Harry Lloyd, and the result would determine if Moir lived or died.

Boyd set the stage with his instructions to the grand jury:

"The deed for which the man Moir stands charged is a horrible one, and one which aroused this province from end to end.

"Shortly before midnight on April 17 a group of soldiers entered Wolseley Barracks. They were challenged by Sergt Lloyd, and hot words are said to have been exchanged between Sergeant Lloyd and Private Moir. Later Moir is said to have entered the guard room. A shot was fired and Lloyd lay dead on the ground.

"There were those prepared to swear that Moir fired the shot, and a search was at once instituted. The city police had been summoned, but Moir has escaped from the barracks. Quickly the authorities organized search parties, and the pursuit began.

"On that first night traces of him were found, but nothing to enable the authorities to form a cordon around the man was brought to light. After the first night the onus of the work of pursuit fell upon Detectives Egelton and Nickle and Sergeant Gilmour.

"Armed with rifles and revolvers, they scoured the country, but without success, and after some ten days the active search was abandoned.

"It was then that a reward for the man's capture was offered, and Constables Farrell and Cochrane discovered and arrested the man on the farm of Mr. Robb, near Arthur.

"Since his arrest Moir has been confined in the county jail. A model prisoner."

That jury, as part of their responsibility during the assizes, was required to hear the evidence which would be put forth at trial and determine if the evidence had enough merit for the case to be arraigned and a trial date set. The jury might return a "true bill," leading to arraignment, or "no bill." The case against Moir was presented by Sidney Smith, K.C., of Stratford, acting for the prosecution. Representing Moir's side was Mr. Ed. Meredith, K.C., who had been acting for Moir since the preliminary hearing months before.

The next morning, 6 October, William Alexander Moir was called forward shortly after the opening of the court. Standing in court, looking none the worse for the living conditions in the county jail, Moir heard the charge against him read by the Clerk of the Court. Moir's posture and attitude relayed a sense of calm to the casual observer. A closer observer, or one familiar with then accused man, might read a level of anxiety in the minor changes of expression and the tenseness of his had gripping the rail of the prisoner's docket. Dressed in a dark suit and light waistcoat with polka dot tie and clean shirt, Moir stood as the charge was read. In response to a request for his plea, Moir replied, "Not guilty, and ready for trial."

Meredith spoke after Moir, confirming the not guilty plea and also claiming that the defence was not ready for trial. Assisted by Matthew Wilson and J.M. McEvoy, Meredith presented to the court their justification for more time to prepare for a trial. Although objected to by the prosecution, Chancellor Boyd allowed that the seriousness of the case indicated that every opportunity for a full and proper defence was affair. He postponed the start of the trial to January, 1909.

The defence argument for postponement included a statement prepared by Moir himself. In it Moir stated that he had no knowledge of the crime, suggesting that he may have been under the influence of an epileptic fit at the time. He claimed to have been afflicted with that disease since childhood and had suffered its effects several times during his four years in Canada. The defence required time to contact Moir's mother and brother in Scotland, and also doctors in Hike, Scotland, for testimony to confirm Moir's medical history. Dr. Robinson, of the London asylum, had also seen Moir for an epileptic seizure and he had confirmed that any history of such attacks was relevant to the case.

Sidney Smith, K.C., the prosecutor, objected to postponement as anyone might expect he would. Already six months after the murder, and five months after the preliminary hearing, he declared the defence had had plenty of time to make their case for further delay. Smith countered with the preparations made to try the case then and there, including the Crown expense to bring a witness from England, a cost that would be wasted if the trial date was delayed. Smith attempted to downplay the likely importance of Moir's childhood medical history and thought the request to postpone only indicated that the defence case was probably a weak one.

Meredith objected in return, countering that the length of time to prepare for trial was reflected in the absence of ready funds to pay for Moir's defence. Those necessary funds, only recently being raised meant that much of the time passed since the preliminary hearing was moot, and only the preceding few weeks dedicated to the necessary work.

Chancellor Boyd was in agreement that the accused deserved every opportunity to prepare a full and credible defence. Acknowledging the loss of considerable expense by the Crown in preparation for fall trial, but he did not support that the request was frivolous or unnecessary. He was amenable to the delay, since it could mean the difference between life or death, or even a mitigating circumstance and leniency in sentencing in the event of a guilty verdict, for Moir.

Boyd declared that such evidence, brought from Scotland in the intervening time, would be important for any jury to consider in Moir's case. The new date set for Moir's murder trial was January, and with that pronouncement, Moir was escorted back to the county jail.

“Moir, the Accused Man-Slayer, Specially Requested The Free Press to Use This Picture of Himself.” London Free Press, 13 Jan 1909.

The Trial; 12 and 13 January

The morning of Tuesday, 12 January, 1909, saw a full courtroom at the assizes, eager to hear the opening stages of the Moir murder trial. Those in attendance were disappointed when the preceding day's business, a damage suit against the Grand Trunk Railway, took up another full day of the court's time.

Moir's trial would start the following day, Wednesday, 13 January. The Crown was prepared to call over 30 witnesses and the defence also had a lengthy list. The crown prosecutor, Sydney Smith, K.C., anticipated the trial might take a day and a half to complete.

The London Free Press set the scene with a dramatis personae:

- The Prisoner

- W. A. Moir, Late Private in No. 1 Company, R.C.R., at London

- The Charge

- That on the night of April 17, 1908. He shot and killed Color-Sergeant Lloyd, also of No. 1 Company, R.C.R.

- Plea of Defence

- That the Prisoner when he committed the crime was in an Epileptic Condition Bordering on Insanity

- The Judge

- Sir William Ralph Meredith, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas

- The Jury

- William Cochrane, Ailsa Craig

- Duncan McKellar, Caradoc

- Thomas Coursey, Lucan

- James Nagie, Caradoc

- David Witherspoon, Ailsa Craig

- Alex. C. McDougall, Caradoc

- Dugald Patterson, Ekfrid

- Arthur Bradhurst, London Township

- William Olds, Ekfrid

- Oliver Nichol, Westminster

- John Goarly, West Nissouri

- John Bogue, Adelaide

The prosecuting and defence attorneys complete the list: Sidney Smith, K.C., and J.B. McKillop were acting for the crown. Ed. Meredith, K.C., J.M. McEvoy and J.H. Wilkins, of Arthur, were Moir's defence counsel.

Once the jury had been selected and charged with their duties, Meredith opened with the presentation of a new theory for the defence. He asked that the jury consider the possibility that Moir had been suffering from temporary insanity at the time of the shooting. On this theme, he asked that the trial begin with examining the question of Moir's mental state. This set aside the prevailing expectation that the defence was working on establishing that Moir was an epileptic and experiencing a seizure at the time.

Also brought forward by Meredith was the statement from a witness who claimed to have between 1500 and 2000 rounds his possession at the barracks when the shooting occurred. This was likely intended to place the idea in the jurors' minds that the barracks were awash with readily accessible ammunition, making the progression from angry altercation to shooting and murder a ready option for a hot-headed or temporarily insane individual.

It was mid-morning before Moir was brought into a courtroom packed with spectators, including a group of young ladies from the local schools of shorthand. Even the hallways and stairs outside the room were similarly crowded. Mostly male, the crowd included medical students eager to hear how the defence case claiming epilepsy or insanity was to play out.

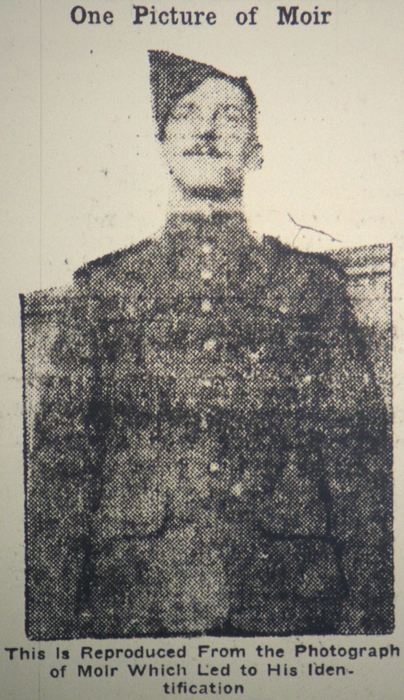

“One Picture of Moir. This is reproduced from the photograph of Moir which led to his identification.” London Free Press, 13 Jan 1909.

The Free Press described Moir's appearance and its contrast to the severity of his crime and the public perception of the kind of man who could commit such an act:

There was nothing of the hardened ruffian about his appearance. What the crowd saw was a lithe young man of medium height, clothed neatly and tastefully in a suit of dark tweed. He wore a gray vest, across which hung a heavy gold chain to which a locket was attached.

He wore a high collar and a large white puff tie, which gave to the man more the appearance of a young divinity student than one who had terrorized a country through which he had travelled armed to the teeth after the slaying of his fellow-soldier.

Moir's dark hair was carefully parted, and at the first he did not show a sign of nervousness. As he took his seat, however, his mouth twitched, and throughout the morning this twitching gave evidence of the uneasiness which the man must feel, despite his otherwise calm demeanor.

Called by the Crown, questioned by Smith and cross-examined by Meredith, the witnesses recounted the events of the night of the murder. Moir's mood that night was described as "peculiar" by Lieutenant Snider and "greatly excited" by Private Hymmen. Smith ensured the jury knew that the defence might claim an epileptic seize of sorts, and reminded them that the disease usually affected motor skills and less commonly the brain alone. The Crown, in Smith's opinion, was ready to prove that Moir was sane, and that the burden of proof otherwise rested upon the defence to demonstrate to the jury's satisfaction.

Meredith advanced his questioning to make a point that that contributing conditions existed prior to the murder which, if they hadn't, may have resulted in a different outcome. With Private Brady on the stand, Meredith questioned him about ammunition in the barracks, confirming that there were 1500 to 2000 rounds in ammunition in his locker in the barrack room. He also confirmed that Brady's pistol was kept loaded, although Brady would not admit to knowing if this was contrary to regulations. That morning's court session ended with Brady's testimony and the remaining of the day would have to wait for the next day's papers.

The afternoon testimony began with Lieutenant George Morris on the stand. No longer serving, Morris had been the second man into Moir's barrack room behind Sergeant Lloyd. Morris allowed that there was a possibility that Lloyd may have managed to grab the barrel of the rifle Moir held before it discharged. He did not agree with Meredith's questioning that Lloyd's actions, in any case, might have been a decisive factor in the rifle firing.

Next up was Charles White, a young boy who lived near The Grove post office. On the 17th of April, fifteen year old Charles had been working with a man named Skinner when they were approached by Moir who wore a khaki uniform. Confirming that the accused was the man he may that day and described how Moir had asked for clothes and Skinner had gone off to find some. When Moir got restless after Skinner had been gone a while, Moir settled for taking Charles' cap and departed.

Herbert Skinner, Charles' companion that day, next testified and corroborated the information given by the boy. He added that Moir's story was that after a night of drinking he was in some trouble at the barracks and only wanted to conceal his uniform for a while. Skinner, while in the house looking for something suitable, had seen Moir's photo in the newspaper, but by the time he returned, Moir was already in the distance, rifle in hand and Charles cap on his head.

The next witness, Albert Martin, lived about ten miles outside of London and had been visited by a man on the night after the murder. Martin could not positively confirm that the man, who had been wearing a kakhi uniform, was Moir. Martin's neighbor, Mr. Dawson, was also visited that night and had loaned the man, who he later realized was Moir, a coat.

Doctor Belton, surgeon of The Royal Canadian Regiment at Wolseley Barracks, testified with regard to his examination of the body of Sergeant Lloyd. Called to the barracks after the shooting, he had found Lloyd still on the floor, and dying. He confirmed the wounds received in the left hand, the right side, and the right arm. He also was questioned on the likely proximity to the muzzle of Lloyd's hand to cause the damage inflicted, and estimated that Lloyd's hand had been within eight to ten inches or possibly even in contact with the muzzle when the shot was fired.

Belton confirmed that Moir had been employed as his groom, and described him as a good man in that regard. He did state that on the afternoon of Good Friday, Moir had been given permission to go to the "butts," i.e., the local firing range, to shoot. Later that afternoon, Belton had observed that Moir had returned and showed obvious signs of having been drinking.

Questioned on the possibility of Moir's actions being the effects of epilepsy, Dr. Belton agreed that alcohol could have brought on such an attack as had been described. He supported that some medical sources spoke of unfamiliar states of epileptic seizure of longer duration and more complex acts and reasoning by the afflicted, but he stated that these were only familiar to him through reading, not from having dealt with such cases.

The tracing of Moir's flight from the barracks ended with the testimony of Charles Robb. He attested that Moir had come to his farm looking for work, and had been hired at a wage of $22 per month.

Witness testimony after Robb turned to the events of Moir's Capture. Fergus police chief Patrick Farrell told of his trip to the farm with Constable Coughlin. The fight to subdue Moir was described and the fact that Moir was armed at the time brought out. Under Meredith's cross-examination, Farrell admitted that he had received $250, half of the reward for Moir's capture, which he did not share with Coughlin.

The murder weapon was identified by Detectives Nickle and Egelton, along with the cap Moir had taken from Charles White. The rifle was also identified by the son of Dr. Hughes of Thorndale, the 12-year-old knowing its number from the receipt for the recovered rifle he had received from Egelton. Sergeant Gilmour, of the Barracks, next demonstrated how the rifle would have been loaded at the time of the shooting and Arthur Courtice confirmed that it was the same weapon which had been in the corner of the barrack room where Moir picked it up before the murder. With these last witnesses, the Crown ended its presentation of evidence, and turned the court over to the defence.

The defence, having taken full advantage of the extra time granted since the fall assizes to prepare, opened with evidence that had been gathered in Scotland on Moir's behalf. These statements were read by Clerk of the Court Weld. It was hoped by the defence that the events they described might help to present a medical history of Moir were presented.

Doctor William Turnbull, of Barrie, Scotland, had seen Moir in the fall of 1905 immediately following a severe epileptic attack, one which had been preceded by drinking. Turnbull had seen Moir after a first attack, though not after a second. The doctor allowed that repeated such attacks could indicate a constitutional tendency toward epilepsy.

Moir's mother, Mrs. Elizabeth Hunter, was also questioned by the commission which gathered information. She described Moir as not a strong boy, but the reasons for which had never been determined by the doctors. After Moir's first service, three years in the Gordon Highlanders, he had returned unwell and that change in him had preceded the attacks now described as epilepsy. Her evidence was corroborated by Moir's half-brother, Charles Scott Hunter.

Dr. Lorraine attended Moir after his second attack, when his mother found him insensible and bleeding from the nostrils. Questioning the man on his drinking habits, Moir displayed his Indian Army temperance medals, gold and silver, to prove his habit of abstinence. Lorraine had not diagnosed Moir's attack as constitutional, i.e., likely to be repeated. He did admit to having also attended to Moir's sister, who had gone insane after being jilted by a young man and from these events concluded that being prone to instability might be a family trait.

With the commission's findings from Scotland presented, the defence began to call its own witnesses.