Disaster at the Barracks

Death and Destruction at Wolseley Hall

By Captain Michael O'Leary, The RCR

Published in the regimental journal of The Royal Canadian Regiment; Pro Patria 2014

Wolseley Hall

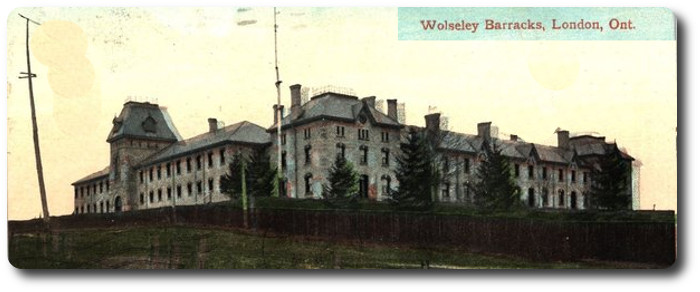

Sitting quietly in London, Ontario, home to two units of Canada's Army Reserve and the regimental museum of The Royal Canadian Regiment, Wolseley Hall is unknown to most Canadians, and even many of the residents of London who pass it regularly. Lost in the background and busy-ness of modern lives and lifestyles, this building holds stories in its brickwork that belie the calm presence of its stately architecture.

Wolseley Hall was built between 1886 and 1888 to house the newly authorized fourth company of the Infantry School Corps. This permanent force unit of the Canadian Militia was established in 1883 to provide schools of instruction for infantry officers and non-commissioned officers of the Militia. The first three school corps companies were established at Fredericton, NB, St Jean, PQ, and Toronto, ON. In 1887 a fourth company was authorized, to be stationed at London, Ontario. Between 1892 and 1901 the Infantry School Corps was renamed four times, becoming on 1 November 1901 "The Royal Canadian Regiment" (The RCR).

As London became the focus for what was to be the first piece of military architecture to be built by a Canadian Government to house a Canadian military unit of the Permanent Force, the city of London was also looking to benefit from the plan. Since the days of the original British garrison in London, the military property had been in what is now the downtown core, around the current site of Victoria Park. Occupied by British garrisons until the 1860s, it continued to be used by the local Militia regiments to the turn of the century when, in the early 1900s, the last of it was turned over with the opening of the new Dundas Street Armoury. By the 1880s, the growing city had its eyes on this prime real estate for expansion and development, and options were developed to trade property on the edge of town for the desirable downtown location.

Three properties were considered, and the one selected was farmland owned by John Carling. This property, still known by some as Carling Heights, was acquired by the city and traded to the Militia Department for the Victoria Park garrison location.

Wolseley Hall was designed by Henry James to accommodate a 100-man infantry company with all modern conveniences. English born and trained as an architect, James began his career with the engineering staff of the Great Western Railway. Emigrating to Canada in 1870, he worked for the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway and in 1873 took a position with the drafting department of the Department of Public Works. By 1886 James had risen to the senior position of Chief Architect for the Militia Department. With this appointment he had the responsibility for the design, construction, and maintenance of militia Drill Halls, military training schools and related buildings in Canada. James compiled a body of work stretching from Kingston, ON, to Victoria, B.C., that included residential buildings, churches, and military edifices.

Listed as a National Historic Site on 28 Oct 1963, Wolseley Hall is described in the Canadian register of historic sites:

Wolseley Barracks National Historic Site of Canada is part of the Canadian Forces Base located within the city of London, Ontario. Also known as Wolseley Hall or 'A' Block, this large, U-shaped structure is arranged around an interior courtyard. The buff-coloured brick building is finished in a classical style with simplified Italianate detailing. Features include a central tower with large arched main entryway for troop access and regularly placed windows. Official recognition refers to the building on its footprint.

True to its purpose as a facility for the training and housing of officers, Wolseley Barracks contained a number of domestic spaces, including a lecture hall and a reading room, as well as a parade ground for drilling and manoeuvres. The eclectic design integrates elements of both contemporary trends in architecture and traditional military design.

Living in a complex piece of architecture, in a challenging climate, one of the struggles faced by the occupants of Wolseley Hall was keeping the building comfortably heated in winter. Sitting as it does on Carling Heights, Wolseley Hall, and any other structures built there, are exposed to chilling winds all winter long.

James' original design included a separate boiler house with two large boilers located in the south end of the inner courtyard, now known as the parade square. This boiler house struggled to heat the complex vastness of Wolseley Hall, and the one tunnel for steam pipes that was built from the boiler house to the centre of the south wing was later augmented by two more tunnels running directly to the east and west wings. (The various entrances to these tunnels are probably the basis of an enduring mythos about old tunnels under the barracks property.)

Even with the addition of extra distribution pipes directly to the east and west wings, the heating system was found lacking in the Canadian winters. In 1898, the heating system was replaced. The new plan placed five large boilers in the basements of Wolseley Hall, including two in the south wing basement, right under the officers' mess. This system was installed by London plumber and steamfitter William Smith. Daily care and maintenance of the heating system was the responsibility of the military duty staff who were charged with keeping the fires burning and the heat on in the massive brick structure.

It was this system of boilers and heating pipework that kept the officers and men of the Infantry School shielded from the cold during long Canadian winters. But the system was not without its issues. In 1900, one of the boilers, located in the east wing, exploded. Although it caused no injuries and the system was repaired, that incident provided a portent of tragedy to come.

In the early hours of the morning of Sunday 27 December, 1903, the heating system would fail again, this time with catastrophic results.

Saturday, 26 December, 1903

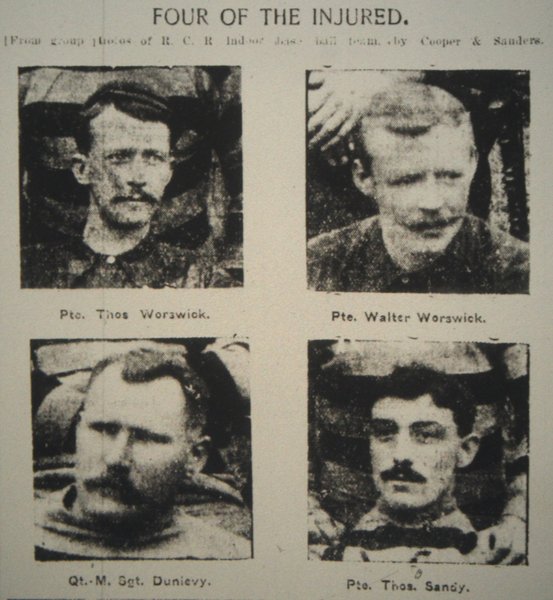

Early in the evening of Saturday, 26 December, the duty men in charge of the furnaces, Privates Thomas and Walter Worswick, 25 and 28 years old, respectively, noticed that things were not running as smoothly as they should. Unable to resolve the issue themselves, the matter was referred up the chain of command until the Commandant, Colonel Young, was informed and visited the furnace room himself.

Convinced that some repairs were necessary, authorization was issued to call in a plumber. Late on a cold Boxing Day evening, the first few firms that were called declined the opportunity to have one of their men making a service call at the infantry barracks. Finally, a positive response was received from William Green, a plumber from the east end of the city.

Arriving shortly thereafter at the barracks, Green replaced a defective pipe elbow on the boiler feed pipe. While there he had no instructions, nor felt it necessary, to inspect the heating system further. On his departure, it was left to the Worswicks to bring the boilers back on line to keep the barracks heated through that very cold night.

Sunday, 27 December, 1903

Well past lights out, most occupants of Wolseley Hall were abed and asleep. Snow earlier in the month and during the previous two days ensured that many soldiers would be envisioning more snow shoveling duties in the week ahead. In fact, the city would be blanketed by 13 centimeters, over four inches, of snow that Sunday. No doubt the anticipated march to Church Parade would give the soldiers plenty of time to contemplate the labour waiting for them on their return to barracks.

But not all of the soldiers were asleep. Two men, brothers, Privates Thomas and Walter Worswick were still up and about as their duties required. They were the men tasked with furnace duty that night, checking the fires under the boilers and watching for signs of trouble in the heating system.

Thomas and Walter, having been machinists in Haywood, Lancashire, England, before emigrating to Canada, had come to the London station of The RCR from Halifax in the fall of 1902. They had been serving there in a Canadian battalion raised to fill the infantry garrison responsibilities when the British Army had pulled their Regular Army battalion out for service in South Africa. While Canada had already raised the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of The Royal Canadian Regiment for service in South Africa, it was the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion that was formed to man the ramparts of the Halifax fortress complex.

In 1902, as the British Army was reducing its strength in South Africa, it was able to return a Regular Army battalion to garrison duty Halifax. The 3rd (Special Service) Battalion was therefore disbanded and the Halifax garrison duties were taken over by the 5th Battalion, Royal Garrison Regiment. The surviving enlistment ledger for the Regiment's London garrison shows that Walter had served in the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion for 247 days. It does not have a similar notation for Thomas.

Some of the disbanding Canadian unit's soldiers, desiring to continue serving in uniform, accepted enlistment in the Canadian permanent force and despatch to garrison locations with vacancies. Thomas and Walter Worswick joined the Permanent Force, enlisting on 8 Oct 1902 on a three-year enlistment, and commenced their duties at Wolseley Barracks.

After eighteen months in London, the Worswick brothers were well integrated into the life of the garrison. Both were well known in sporting circles and represented the barracks on a variety of teams throughout the year. With no relatives in Canada to think of visiting this weekend following Christmas Day, the Worswick brothers found themselves patrolling the gas lit hallways in the basements of Wolseley Hall checking the fires under each great boiler.

Around midnight, Saturday night, the two brothers were examining the boilers in the basement of the south wing under the officers' mess. Thomas had heard rumblings in the furnace workings of the boiler room and, feeling uneasy, had brought his brother down to get a second opinion.

Unable to determine the cause, the brothers took action to inform the Officers' Mess Sergeant, an appointment held by Lance-Corporal James Burnett. Burnett had also come to London in 1902 from Halifax at the same time as the Worswick brothers. Having served with the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion for 329 days, Burnett enlisted in the Permanent Force on 3 Oct 1902 at the age of 36. Having served together in Halifax and in London, Burnett and the Worswicks would have been known to one another and Burnett likely would not have dismissed the brothers' concerns over the heating system lightly. Burnett would also have been aware that a local plumber had been engaged the previous evening to work on the boilers under the Mess and the concerns that led up to his being called to the barracks.

Burnett also could not determine the cause of the rumbling noises and, sharing the Worswicks' unease, the decision was made to take the matter higher. Accordingly, Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy was woken. Dunlevy was in charge of the infrastructure of the barracks and so responsibility for the functioning and monitoring of the heating system fell within his bailiwick. Dressing quickly in his uniform and throwing on his greatcoat, he followed the Mess Sergeant and two soldiers back to the basement to inspect the boilers.

Despite their general concern, the four men could determine no specific cause for the noises. They attributed it to the strength of the fires burning under the boilers, perhaps not an unlikely cause since the 26th had been the coldest day of the year, with low temperatures reaching -17.8 degrees Celcius (0 degrees Fahrenheit).

It was as the four men were about to leave the boiler room that disaster struck. Shortly after midnight, as the men were still in the boiler room, the first boiler reached a critical pressure and exploded.

That boiler, eight feet wide and 24 feet long, sitting three feet from its neighbour in a heavily built room with stone foundation walls, was a potential catastrophe needing only to reach its point of no return. When it did, the blast, the shrapnel of disintegrating boiler plate and pipework, and the released super-heated steam and hot water, turned that basement room into a veritable hell.

The First Explosion

Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy, Lance-Corporal Burnett, and Privates Thomas and Walter Worswick were preparing to leave the boiler room under the Officers' Mess in the south wing of Wolseley hall. They had decided that the mysterious rumbling noises heard in the boiler system were an effect of the steady fires and the heated water. Seeing no obvious signs of danger, they decided to leave the system alone and trust that it was functioning properly.

Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy was in the lead, followed by Walter and then Thomas Worswick. They were about to mount the stairway leading up to the entryway of the Officers' Mess. Burnett, last of the party, was a few paces behind the Worswicks. He stood opposite the gap between the two huge boilers at the moment of crisis.

The blast rent one boiler asunder, releasing its contents into the confined spaces and narrow passageways of the basement. The explosion there the four men outward, their bodies striking the stone walls that interceded their trajectories. Dazed by the shock and concussion, deafened by the noise, enveloped in the released steam and boiling water, each man was left to his own fortitude and resources to escape that subterranean Abaddon.

The fearful rending of tearing boiler plate iron and a blinding flash of light assaulted the men's senses. Broken plate and pipework turned to shrapnel, billowing clouds of superheated steam and a cascade of boiling water turned the room into a death trap. Each man had but one choice for survival, remain and be cooked alive by the steam and water, or escape as best they could. Overwhelmed by the massive sensory overload, there was no time in those precious first seconds after the explosion to seek or offer help.

Beyond throwing these four soldiers against the stonework, and assaulting them with fractured metal and superheated steam and water, the blast shook the building from basement to rooftops. Every other man in the barracks was instantly awoken, and many started moving, as soon as they could, towards the point of crisis and the courtyard parade square, to see what was the cause of their sudden rousing.

In the next room beside where the boilers were housed, two more members of the garrison force were violently roused when the explosion threw them from their beds. Corporal Thomas Sandy, a 25-year-old officers' mess cook, and Private Herbert Tutt, a 20-year-old mess waiter, slept in a stone-walled room next to the boiler room. The wall, which protected them from the flying debris of the blast, did not stop the concussion from throwing Sandy, who was closest to the blast, fifteen feet from his cot.

Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy managed to stumble up the stairs to the officers' mess, barely escaping the worst of the enveloping clouds of steam. Here, he was found, badly bruised and scalded, by Corporal Evans. Dunlevy was disoriented, unable to find his way out of the building. He was suffering already from the effects the superheated steam that he did inhale, the scalding of his lungs an immediate and unfortunate result.

After scrambling over the shattered remains of the exploded boiler, Walter Worswick followed Dunlevy up the stairs. The few steps behind Dunlevy that he stood at the moment of explosion had a cost. He was more exposed to the explosion, and the steam reached him in greater densities before he could mount the stairs. He too suffered greatly from the steam he inhaled. Corporal Evans, assisting both men, saw them conducted to the barracks hospital in the east wing of the building.

Corporal Burnett and Thomas Worswick, thrown as they were by the explosion, were, by their locations and disorientation, unable to follow Dunlevy and Walter up the stairwell. They groped their way in opposite directions from the devastated boiler room in the pitch darkness, the blast having blown out all of the gas lighting. Their immediate unfortunate circumstances meant that each was exposed to the frightful environment in the boiler room for longer that the two who made it to the officers' mess stairs.

Dunlevy had been protected by his clothing and greatcoat. The Worswicks, on the night duty, were each fully dressed. But Burnett, having been roused to check the boilers after the Worswick expressed concern, was wearing only an undershirt and trousers. His body was more exposed, and he was intimately closer to the point of the blast than any of his companions.

Lance Corporal Burnett was within arm's reach of the exploding boiler. To add to his torments, as the water and steam enveloped him, the crashing boiler pinned him to the floor. The moment it took him, through some superhuman effort, to roll the remains of the boiler off his body must have been excruciating as he was pinned to the floor in the boiling water released from the shattered metal container.

Corporal Sandy rose from the floor where the explosion had thrown him from his bed. He was bruised and bloody from his brief flight, but thankfully close to a window. His own survival instincts kicking into play, Sandy exited the building through that basement window, the glass having been blown out by the boiler's blast. Once he was safely outside, he helped his companion through the shattered windowpane. In getting through the window, Sandy received a number of cuts about his neck which would require treatment by the barracks surgeon. Barefoot and barely dressed, in the immediate aftermath of the explosion he found himself standing outside during one of the coldest nights of the winter.

Thomas Worswick made his way into the basement barrack room which had been occupied by Sandy and Tutt. It was here that Sandy called to him from the broken window and then assisted his escape, joining Sandy and Tutt outside.

One of the first men on the barracks parade square was Lieutenant Douglas Young of the Royal Canadian Dragoons. On leave from the Toronto garrison, he was spending the holidays with his father Colonel D.D. Young, who commanded Wolseley Barracks. Even as Lieutenant Young attempted to organize a rescuing party from the soldiers who had started to gather outside, the hissing release of pressure from the boilers could still be heard. Before any could move into action, Dunlevy exited the parade square door of the officers' mess, indicating that escape, at least for some, had been achieved.

Burnett's escape from that hellish basement was an even greater ordeal. Last to escape the boiler room, who heard his cries but were unable to turn back into that maelstrom to assist; he was forced to free himself from the boiler wreckage. He escaped the boiler room in the direction of the kitchen, leaving a trail of bloody handprints to mark his excruciating progress. So devastating was the effects of the heat, hot water and steam on his skin that at one point, pulling himself to his feet in the kitchen, the skin of one finger tore free and slipped from the digit like the finger of a glove. It was here in the kitchen that he too was rescued by men outside who drew him up through a broken window,

The Second Boiler

Colonel Young joined the gathering throng on the parade square. Immediately after the steam of the explosion subsided, he ventured down the stairs and made a brief inspection of the boiler room. Assessing the damage he began his return to the parade square. As he was on the stairs coming from the basement, the second boiler exploded. Protected by the sturdy basement walls, Colonel Young narrowly escaped being a further victim of the failed and failing heating system.

This second boiler ruptured in such a way that it was thrown violently against the ceiling of the basement room. Luckily, it caused no greater damage than some doors being wrenched from hinges by the force of the blast (including one as much as sixty feet from the point of explosion), loosened floorboards from the upward jolt, and a variety of broken dishes in the officers' mess. Wolseley Hall, well-built that she was, suffered more by the indignity of the explosions than by any physical result other than the self-destructed boilers.

Perhaps in sympathetic response to the double shock, or perhaps because it was similarly aged and worn, the boiler under the sergeants quarters started acting strangely and a pipe burst, the debris shattering a window. A feared potential third explosion was averted when soldiers were sent to rake out the fire and stop the boiler.

Caring for the Wounded

Corporal Burnett and Thomas Worswick, both severely injured in the explosion, were transported by their rescuers them to the hospital rooms in the east wing of Wolseley Hall. Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy and Walter Worswick were also taken to the barracks hospital room. All four men had suffered terribly from being in the boiler room at the time of the explosion. They each suffered from varying degrees of scalding, both to their lungs and to their bodies. The bruises and cuts each had were the effects of being bodily thrown by the explosion and the result of the broken parts of boiler and pipe which ricocheted around the room.

Each of the four men had used the last of their strength to get away from the point of danger. Fighting the effects of their diverse wounds and burns, each made it to a point of exit, where they were helped through and, once in the arms of comrades, were swiftly taken to receive medical care.

The garrison surgeon, Surgeon-Major (Dr.) C.W. Belton, was summoned. In the hospital room, the men came under the immediate care of Hospital Sergeant Ardiel, who did everything he could to make them comfortable and care for their wounds. What could be done was done, and Surgeon-Major Belton had high praise for Ardiel's actions in his care of the wounded men.

Cassius Wilkinson Belton was appointed a surgeon-major for The Royal Regiment of Canadian Infantry (later The RCR) on 17 June, 1897, at the age of 36. He would be promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the Permanent Army Medical Corps on 2 July, 1904, and later attain the rank of Colonel in the Canadian Militia on 24 May 1916. He would later be known as the author of "Pensions for the disabled soldier: Canadian Expeditionary Force," published in 1919.

Recognizing immediately that the injured men required care beyond which the garrison facilities could provide, Belton had the city ambulance summoned. Burnett and the Worswick in particular, beyond their outwardly physical injuries, immediately suffered from difficulties in breathing brought on by scalded lungs. This condition could not be treated in the garrison medical facility, although little more could be done at the city hospital.

The new city ambulance, however, could only transport one patient at a time, and it made two trips to convey two of the more grievously wounded men. The old city ambulance, pressed into service, carried the third.

Death of Lance-Corporal Burnett

Lance Corporal James Burnett died at 6:30 a.m., approximately six hours after the first boiler exploded. Suffering indescribable torments from injuries visible and unseen, he maintained consciousness throughout his ordeal, uncomplaining, and even speaking with his caregivers and visitors on occasion.

It was accepted by the doctors that they could not save him. The damage to his lungs was sufficiently severe that his demise was described as little more than "prolonged suffocation." Burnett's other injuries included severe burns to his face, body and limbs. He had skin peeled away from "foot square" areas of his body, some of this undoubtedly damage from when his well-meaning rescuers lifted and pulled him through the basement window. His legs, upper body and face were the most affected. In addition to his burns, Burnett had suffered a serious head wound from flying debris.

During his slow death at the hospital, Burnett remained in good spirits. He denied his suffering and claimed that he would recover, but his fate was not in question.

While the available reports allude to Burnett's severe injuries, they are not specifically detailed. The following, from a more recent incident, offers a glimpse of what Burnett experienced and suffered.

Arland "Dean" Stackpole, a steam fitter and operator at the Brunswick Naval Air Station in Brunswick, Me., entered a steam pit in October 1997 to open a 14 in. cast iron valve. The valve's handwheel erupted in an explosion of steam and condensate as he reached for it. His injuries were described as follows in the HPAC Engineering magazine (July 1999):

The force of the steam struck Dean full in the face, destroying the flesh from the right side of his head to his nose. The 8 x 8 ft pit filled rapidly with condensate, immersing the lower half of Dean's body in 212 F scalding water. … Steam pouring into the pit obscured everything. He was lost in the 8 x 8 ft vault. Desperately, he headed for the nearest wall. He had to breathe. … With an elbow over the rim [of the 8-foot deep pit], he dragged himself up and out of the pit, rolling out onto the ground. … Dean had lost all the skin below his waist. Muscle and bone were exposed beneath his knees, on the side of his head, and on his hands. His face was badly burned. … Recognizing that Dean's air passage was closing, emergency physician Dr. Van Derputten saved Dean's life by intubating him just before his throat closed off completely. Dean was airlifted by Navy helicopter to a burn unit in Portland Me. within 30 min and, from there, driven to Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital burn unit. There his lungs failed, but by now, he was in the hands of Dr. Robert Demling, who saved his life once again. For the next several weeks, Dean was sedated and breathed through a respirator. For another month after that, he had to breathe through a tube down his throat. He required skin grafts over 70 percent of his body and re-constructive surgery to his face and hands. The process went slowly since there was twice as much burned area to graft to as healthy skin to harvest. Today, a year and a half later, Dean speaks with a hoarse and whispery, but enthusiastic, voice. He does volunteer work with other burn victims [and has returned to work since the accident].

"Dean" Stackpole's injuries were likely even more severe that Burnett's and it is a testament to the advances in medical technology and practices that he survived where little could be done for Burnett in 1903.

Death of Private Thomas Worswick

Thomas Worswick, also badly burned and with seriously scalded lungs, lay in hospital where the medical staff assessed his injuries. Although not quite so clear a case as Burnett's, the staff of the hospital held out little hope for Thomas' recovery. Although Thomas' external injuries were not considered sufficient to expect his demise, the degree of damage to his lungs and its effects was yet to be determined.

On Monday, the day after the explosion, Thomas' condition was assessed as marginally but noticeable improved. But early in the morning on Tuesday, 29 December, his condition began to decline. By 9:30 that morning he too had succumbed to his injuries, the principal cause being the damage to his lungs from the steam released by the boiler.

Walter Worswick and Q.M.S. Dunlevy

Private Walter Worswick and Quartermaster-Sergeant Dunlevy were luckier than their companions in the boiler room. Over the following days, each showed improvement. Walter's case was sufficiently serious that it was decided not to inform him of his brother's death for some days afterwards, in order to ensure he was strong enough to sustain the shock of the news.

Walter's injuries included burns, bruises and other injuries from the blast and debris. Quartermaster-Sergeant Dunlevy, having been almost out of the room at the time of the explosion, suffered most from having his foot badly crushed by debris, an injury that would be a long time healing.

The Aftermath of the Explosion

As the wounded men lay suffering and dying in hospital, the Infantry Barracks was left with the pressing problem of a destroyed heating system in mid-winter. One unanticipated, yet immediate, problem arose when curious crowds of London citizens began to arrive at the barracks, hoping to see the effects of the great explosion, of which rumours quickly spread through the city. The crowds, numbering in the hundreds, gathered despite the snowfall that day which accumulated to over 12.5 centimeters (5 inches). This problem, however, had a simple solution, and Colonel Young ordered that no outsiders were to be allowed on the barracks grounds.

With temperatures having dipped to lows of -18ºC (0º) on the 26th, the day before the explosion, to -16º (3º) on the 27th and to -14º (7ºF) the following day, heating the barracks was a pressing priority. The necessity to inspect damage and investigate causes meant that effecting hasty repairs to the existing boilers under the officers' mess was out of the question, even if the extent of the damage had not made doing this quickly an impossibility. Instead, the local firm of Stevely & Son was contracted to install gas stoves throughout the south wing apartments to heat the officers' quarters, the mess and other rooms in the six sections of the south face of Wolseley Hall.

An Inquest is Convened

In the days following the boiler explosion, plans were made for a military court of inquiry to be convened, and a Government engineer was sent for. The coroner, Dr. J.M. Piper, was also called, but as of the evening of the 27th, the day of the explosion, he had not yet committed to calling a jury for an inquest. The military inquiry and a coroner's inquest, if called, were separate administrative processes, which could be executed in parallel without either being affected by the other.

With the death of Lance Corporal Burnett, Dr. Piper convened a Coroner's Inquest on Monday, 28 December to determine the cause of death. The jury was called that same date, and met in the rooms of the W.J. Smith & Son funeral home where they were empanelled and viewed the body of James Burnett. The members of the inquest were met in the undertaking rooms by Private Sandy who identified the body of Lance Corporal Burnett for them.

The members of the inquest jury were (details of employment and residence are taken from Foster's London City and Middlesex County Directory 1903, Seventh Edition):

- Samuel Turner (foreman) – carriage maker, 347 Ridout (home same)

- John E. Platt – druggist, 389 Talbot

- David Tripp – shoemaker, 96 King, home 31 Bathurst

- Robert A. Ross –grocer York, corner Thames

- William Payne – (4 possible men)

- William Row – shoemaker, 344 Ridout, home 85 Wharncliffe Rd S L

- Fred Highway – (not found in Directory)

- Thomas Cousins – pump manufacturer, 123 Bathurst

- Alfred Johnston – (3 possible men if Johnson, 2 possible if Johnston)

- Israel Quick – painter 190 Colbourne

- John Quait – rooms 78 1/2 Cheapside

- Robert Gillespie – lives 125 Oxford

- Alfred A. Keene –salesman F.B. Keene, home 66 Palace

- John E. Thorne – (of Thorne Bros., boots and shoes) 454 Ridout

Police Sergeant Crawford was appointed to serve the jury.

The inquest was called at 8:15 p.m. and at 10:15 p.m. the same evening was adjourned. They would meet next on the 11th of January at the police station. This postponement would allow time for expert witnesses to inspect the site of the boiler explosion and prepare reports.

A Double Military Funeral

James Burnett succumbed to his injuries on the morning of 27 December, six hours after the explosion. While Thomas Worswick still clung to life, arrangements were being made for Burnett's funeral. The papers of the Tuesday, the 29th, reported that Burnett's funeral was scheduled for 2:30 p.m. on Wednesday, 30 December, and that he would be buried with full military honours by the officers and men of No. 1 Company of The Royal Canadian Regiment. It was stated that the funeral procession would move from Wolseley Barracks to Mount Pleasant Cemetery on the west side of the city.

As planning for Burnett's funeral continued, the tragic news of Thomas Worswick's death reached the barracks. The decision was taken to postpone Burnett's funeral, and to conduct a double funeral on Thursday, 31 December.

A few blocks south of Wolseley Barracks, on the corner of Queen and William Streets, is the Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church. This church, consecrated in 1873 and continuing a local Anglican parish tradition dating back to 1860, became a garrison church for the Infantry School Corps and other elements of the Permanent Force at Wolseley Barracks. The long association of The Royal Canadian Regiment with Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church, named for the First Bishop of Huron (1871-1884), remains in evidence. The first King's and Regimental Colours of the Regiment, laid up in the chapel in 1932, can still be seen in a protective case in the sanctuary.

It was to Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church which the soldiers of the Church of England (Anglican) faith (or at least those not of the Roman Catholic tradition) marched for Sunday church parades. It was here that those members of the garrison might be wed, have children baptized, or have conducted the funerals of family members. Sadly, in this case, it was two members of the regimental family of the garrison who would have final prayers read over their remains.

In 1903, the Rector of Cronyn Memorial was Reverend Dr. Dyson Hague. Toronto born, Hague had been educated at Upper Canada College, University College (BA and MA), and Wycliffe College (DD). He was ordained in 1883 and, before coming to London, had served as the first rector of St Paul's Church in Brockville, Ontario, in 1885, and the seventh rector of St Paul's Church in Halifax, NS, from 1890 to 1897. He was appointed rector of Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church in 1903 and would be named honorary canon of St Paul's Cathedral in London in 1908. St Paul's Cathedral in London was, and continues to be, the "garrison chapel" for the 4th Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, the Reserve battalion of The RCR, which also continues the legacy of the city's militia regiment, the Canadian Fusiliers, and it is here that more Colours of the Regiment can be seen. After 1912, when Hague left London, he would serve as rector of the Church of the Epiphany and professor of liturgics and ecclesiology at Wycliffe College in Toronto.

Even though Reverend Hague was recently arrived in London, he would have been no stranger to the role and responsibilities of ministering to a military garrison. St Paul's in Halifax, where he had served for seven years, was one of the garrison churches in that city and today the walls of that church are covered in memorial plaques to many generations of soldiers and sailors. Reverend Hague would perform the funeral service at Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church, but he would leave the committal ceremony at Mount Pleasant Cemetery to his assistant, Arthur Carlisle. At Mount Pleasant, James Burnett and Thomas Worswick would be interred in adjoining graves.

The King's Regulations and Orders state that "a military funeral will be accorded to an officer or man buried within the district occupied by the troops with which he is serving at the time of his death, provided troops are stationed within a reasonable distance from the burial ground; but if any expense is involved for the use of a gun carriage or the attendance of soldiers, such military funeral will not be ordered without special authority."

The issue of transporting the remains was obviously a matter of discussion. According to the Regulations, when a soldier is buried with military honours, the body is transported on a gun carriage. But, in order to control expenses, those same regulations state "gun carriages or other appliances will be supplied when available at the station, and only when the burial ground is distant upwards of one mile from the place from which the procession starts." Unfortunately, the London Field Battery had been disbanded a few years before and there was no available gun carriage in the London garrison. As an alternative, it was decided that a sleigh, appropriately draped in black and tied with purple, would be used to carry the two coffins.

As in so many things, the rank of a soldier in life or in death determines what privileges and honours he might receive. In accordance with the King's Regulations and Orders, in which the entitlements for military honours at funerals were detailed, plans were made for the funerals of Lance Corporal James Burnett and Private Thomas Worswick. For soldiers below the rank of Sergeant, the authorized funeral salute to be conducted by the firing party was three rounds of small arms fire, i.e., three volleys, the same standard that exists today.

The regulations also detail the requirements for pallbearers, curiously worded as specific to officers; "The pall is to be supported by officers of the same rank as held by the deceased, but if a sufficient number of that rank cannot be obtained, officers next in seniority are to supply their places." Also, in addition to the firing parties, "the funeral of a N.C.O. or private will be attended by the company, &c. (officers included) to which he belonged, or was attached."

Basing their planning on the expectations set out in King's Regulations and Orders, No. 1 Company of The Royal Canadian Regiment would be well prepared to bury their fallen comrades.

The Procession and Service

Four days after the explosion, the funeral procession assembled at Wolseley Barracks on the afternoon of Thursday, 31 December, 1903, to convey and escort the bodies of Burnett and Worswick to Bishop Cronyn Memorial Church and then to Mount Pleasant Cemetery. It is indicative of how quiet a town London was in the early 1900s that the double military funeral was reported in the London Advertiser, a local newspaper, as an "imposing spectacle." On a day during which the temperature would rise no higher than -14ºC (6ºF), and a fresh 4.8 cm (2 inches) of snow would fall, large numbers of London citizens turned out to watch the procession and attend the funeral service.

Shortly before 3:30 p.m., the funeral sleigh was positioned outside the doors of Wolseley Hall. The formation of the procession proved how closely the lives and camaraderie of the Permanent Force and Militia soldiers of the town was intertwined. Both of the city's infantry Militia units, the 7th Regiment, Fusiliers, and the 26th Regiment, Middlesex Light Infantry, had numbers of soldiers falling in for the solemn duty of saying farewell to these two respected soldiers. In addition, Lieutenant Colonel Young, the Commanding Officer of the Fusiliers, had authorized the Band of his regiment to play for the procession.

Formed for the solemn processional march to the Church, the column consisted of the firing party, then the band of the 7th Regiment leading the draped sleigh. Following the funeral sleigh were the chief mourners, with the soldiers bringing up the rear, and the officers of the garrison last in line. For those who carried arms, these arms were reversed and in this configuration the procession marched from Wolseley Barracks to Cronyn Memorial Church.

Every pallbearer for the double funeral was a non-commissioned officer or soldier of The Royal Canadian Regiment. Those who acted as pallbearers for the late Lance Corporal Burnett were:

- Sergt.-Instructor Harry Russell Hebkirk (Regt No. 4230). Already an old soldier, having served in the regiment since enlisting in 1886 at the age of 18, Hebkirk would complete 26 years with the Regiment before being discharged in 1912 at the rank of Quartermaster-Sergeant with an Exemplary character.

- Quartermaster-Sergeant Alfred Blake Blake-Foster (Regt No. 3536). With a decade of service in the Regiment since 1893, Blake-Foster had emigrated from Gloucester, England, and joined the Canadian Permanent Force at the age of 23.

- Colour-Sergeant David Cranston (Regt No. 3005). A land steward from Lancaster, England, Cranston had joined the Infantry School Corps in 1887 at the age of 27. He was a veteran of the 1885 North-West Rebellion and would receive the Queen's Golden Jubilee Medal.

- Hospital-Sergeant Alfred Ernest Ardiel (Regt No. 7189). A trained druggist, Ardiel had enlisted in March 1902 at the age of 25. He would continue to serve with the Regiment until he transfered to the Permanent Army Medical Corps.

- Sergeant Walter Henry Beales (Regt No. 3776). An ex-brass finisher from Stratford, Ontario, Beales had joined the Regiment in 1895 at the age of 22.

- Corporal William

HenryHerbert Walsh (Regt No. 3319). Walsh had joined the Regiment as a boy soldier in 1890 at the age of 11 years, 8 months. Remaining in London, he would serve until purchasing his discharge in February 1904. Re-enlisting in 1906, Walsh would finally be discharged from The RCR in Halifax in 1916 at the rank of Sergeant Instructor, his character being recorded as "Indifferent." He married in 1901 and would have four children with his wife Margaret, between 1903 and 1910, all born in London. - [16 Nov 2019: Information received from the grandson of W.H. Walsh has confirmed that although both "William Henry" and "William Herbert" were recorded in a regimental enrollment ledger, the correct forenames for W.H. Walsh are "William Herbert." The Walsh's family would also grow to include seven children. It was also confirmed that after his 1916 discharge from The RCR, Walsh re-enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at London, Ont., with the 1st Depot Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment, serving from 1 Oct 1917 until 12 Aug 1918. His rank and character on discharge from the C.E.F. were Sergeant-Major and Good, respectively. W.H. Walsh went on to serve in the Canadian Militia as a member of the Seventh Regiment Band. Walsh died in 1937, unfortunately suffering a heart attack while in the rooms allocated to the Veteran's Band at the London Armouries, he had shortly before been appointed bandmaster of the Veteran's Band and was preparing to begin his first practice in that appointment.]

- Corporal Thomas Francis Walsh (Regt No. 7001). While there is no indication that the Walshes were brothers, it is quite possible. Thomas Walsh joined the Regiment in 1894 at the age of 15 years, 11 months. He too would remain in London for much of his career, taking his discharge in 1905, re-enlisting in 1906 and marrying in 1907, with one child born in 1908. By 1918, when Thomas Walsh attested for overseas service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force at the age of 37, he was able to report having served 17 years with The RCR and three years with the 7th Regiment, Fusiliers.

- [16 Nov 2019: Information received from the grandson of W.H. Walsh has confirmed that William Henry Walsh and Thomas Francis Walsh were brothers.]

The pallbearers for Private Worswick were:

- Private Thomas Sandy (Regt No. 7132). A labourer from Yorkshire, England, Sandy had joined the Regiment at London in February, 1900.

- Private Frederic William Chaplin (Regt No. 7171). A machinist from Suffolk, England, Chaplin had joined the Regiment at London in 1901.

- Private Herbert Tutt (Regt No. 7186). A farmer from Suffolk, England, Tutt enlisted with the Regiment in 1902 at the age of 19. He would take his discharge in January 1905 after serving a single three-year engagement.

- Private James Lawrence (Regt No. 7213). A London, Ontario, born clerk who joined the regiment in 1902 at the age of 18, Lawrence would later transfer to the Permanent Army Medical Corps.

- Private William Henry Prouse (Regt No. 7196). Having enlisted in the Regiment in July 1902. Prouse would serve until taking his discharge at Valcartier Camp in July 1920. He would marry at London in 1904 and have two children, born in 1905 and 1909.

- Bugler John Henry Ernest Fitzallan (Regt No. 7212). A law clerk from Delaware, Ontario, Fitzallan joined the Regiment in 1903 at the age of 17 years, 6 months. By July 1905 he would be a Lance Corporal on his transfer to No. 2 Regimental Depot.

The firing party consisted of the following: Sergeant Evans, Corporal McFadden, and Privates Campbell, Harlow, Horner, Jackson, Levins, McKeown, Miller, Truesch, Tutt, Walliker, Gilbert, and McMahon.

The funeral procession was met by Reverend Hague shortly after 3 o'clock in the afternoon. Armed soldiers, resting on their arms reversed, lined the walkway from the street to the church doors, and between this silent homage to their comrades, Rev. Hague led the two caskets into the church, intoning as he went: "I am the resurrection and the life."

The caskets were placed at the top of the sanctuary. The church was draped in funerary black, and the Reverend followed the simple yet impressive funeral service of the Church of England. Hague's homily spoke of the need for all to be aware that death was not a punishment for sin, and even good Christians might be called to their Lord by untimely death.

With the conclusion of the service, the pallbearers again took up their solemn burdens. As they slow-marched from the church sanctuary the church organist, Miss Moore, played Handel's "Dead March." The procession assembled outside the church and began its measured progress along Queen's Avenue, Richmond Street, and Dundas Street toward Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

At the cemetery, the final words of committal for the interment of Burnett and Worswick were delivered by Mr. Arthur Carlisle.

Born in Portsmouth, England, in 1881, Arthur Carlisle attended Western University, in London, Ontario and later studied theology at Huron College. He was ordained Deacon in 1904 and entered the priesthood on November 30, 1905. His first appointment as Deacon was as Assistant at Cronyn Memorial Church, London, and it was in this appointment that he conducted the committal service for Burnett and Worswick. Carlisle afterwards moved to the parish of Lucan and Clandeboye, and then to All Saints, Windsor, in 1910. In 1914, he returned to a role of ministering to soldiers as Chaplain to the 18th Battalion, C.E.F., which was raised in Southwestern Ontario In 1919, after the First World War, Carlisle returned to London and was made a Canon of St. Paul's Cathedral, London, Ontario. His career led to his election as Bishop of Montreal in 1939, a position he held until his death on January 5, 1943.

As the coffins were lowered, the troops stood at the position of "Present Arms" in a final salute and the firing party fired three volleys over the quiet cemetery. The deaths and burial of both Burnett and Worswick were recognized, both within their military social circles and by local civilians as well. As recorded by the Daily Free Press on 1 January, 1904, flowers were sent to the funeral by a number of parties:

"Handsome floral tributes were sent to each by Col. Denison, captain of their company; Col. Young, and the officers of the depot, and from the Lord Roberts Chapter of the Daughters of the Empire, of which Mrs. Denison is regent. The sergeants' mess also sent two wreaths, and there was one sent by Mr. A. Wolf for Lance-Corp. Burnett, and a very nice tribute from Woodstock Cricket Club. Three young ladies sent a pretty wreath to be laid on the grave of Private Worswick."

The Inquest Continues

The Coroner's inquest jury reconvened at 8:15 p.m. on the evening of Monday, 11 January. Witnesses were called before the jury were:

- Colonel Young,

- Surgeon-Major Belton,

- William J. Green, plumber, and

- William Smith, plumber and steam-fitter.

Colonel Young testified to the facts of having brought the plumber, Mr. Green, to the barracks earlier in the evening before the explosion to effect repairs. Green had replaced a defective pipe elbow, and Colonel Young instructed the Worswick brothers, who were on duty to monitor the heating system boilers, to restart the boiler furnaces to counter the cold winter night. The western boiler of the pair was started at 10:00 p.m., and the eastern boiler, which had exploded first, at 12:00 p.m. Before Young left the basement, he spoke with the Worswicks about the boiler valves, which they were operating. The brothers were adjusting the valves on pipes leading to the boilers and they had informed the Colonel that all was correct and they had the valves turned on.

Shortly after returning to his own quarters, at 12:30 a.m., Colonel Young heard the sounds of rattling pipework and the thud of the exploding boiler. He followed his son into the barracks court yard, where he saw the injured men and made a brief inspection visit to the devastated boiler room. It was between this visit and the readying of men to go into the basement to rake out the fire of the second furnace that the western boiler also exploded. Only a few minutes earlier or later, and the second explosion would have added to the casualty list.

Colonel Young confirmed to the jury that is was the customary duty at the barracks to have two men assigned to monitor the boilers. In this work, it was Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy's responsibility to instruct and supervise those men. Colonel Young also noted that he was aware of problems with the heating system before he came to the barracks, a likely allusion to the 1900 explosion that was not detailed by the reporter covering the inquest. He noted that since that incident, it had been recommended that the valves should be "connected with a chain."

Surgeon-Major Belton's testimony detailed the injuries to all four men who had been in the boiler room at the time of the explosion. At that session of the inquiry, he estimated that Dunlevy and Walter Worswick would likely be in hospital for another week as they continued to recover from their injuries.

William J. Green, a London plumber, also testified before this session of the coroner's inquest. He stated that he was the plumber called on 26 December, the evening before the explosion, to conduct repairs on the heating system. His concern during that visit was the repair of the elbow on the hot water heating system and he had received no request to inspect any other part of the system. He stated that the faulty elbow, a cast iron part, had burst due to frost. While doing his work, he had observed the Worswick brothers working on the east boiler, installing grate bars. Green also confirmed to the jury that the valves controlling the flow of water into and from the boilers had to be turned on while the furnaces were in operation. If not, he stated, an explosion would be the result.

Green was followed by William Smith, another local plumber and steam fitter. Smith had executed the 1898 contract to install the boiler system in the basements of Wolseley Hall which replaced the separate boiler house. He explained to the jury the nature of the twin boiler system, with the valve arrangement such that if only one boiler was operating, it would continue to support the heating system. Smith reinforced the theory that the explosion must have been caused by inappropriately closed valves. He stated that even if only one of the feed or return valves was closed, it could cause a boiler explosion, but if both were closed when they should have been open, the explosion would be much more serious.

William Smith had also been called to the barracks after the first boiler explosion in 1900. At the time, he confirmed that an incorrectly shut valve was the cause of that explosion. After that incident, he had recommended changes to the valves, including the addition of securing chains and locks with the key held by a single individual who would control the valve settings. This recommendation had not been executed,. Smith was confident that the explosion on 27 Dec 1903 was caused by having all four valves for the two boilers closed when they should have been open.

Smith had testified that the heating system should not have required a dedicated "practical man" as long as clear instructions were available and followed. The men working the furnaces, he declared, should have understood which way the valves needed to be turned, or they should not have been operating them at all.

After the two plumbers had spoken before the inquest jury, one of the jurors requested that Colonel Young return as a witness. In response to questioning Colonel Young confirmed that he had not ordered the men to turn off the valves, and as he understood what the valves did, he failed to understand why the men had been operating the valves at all. The Colonel confirmed that it was Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy's duty to ensure that the men on furnace watched understood the importance and operation of the valves. While in the furnace room, Colonel Young was unable to determine whether the valves were open of closed, the construction of teach valves was such that their state could not be determined by looking at them.

It was also brought forward during this sitting of the inquest that the cause of the explosion in 1900 was rumoured to have been a prank played by someone in the barracks. This possibility was examined and Colonel Young admitted that it was possible that someone other than the Worswicks may have been in the basement and changed the settings of the valves.

Having completed its work for the evening, the inquest jury adjourned, and would reconvene the following week on 19 January.

The Inquest Continues

The jury reconvened for the Coroner's inquest reassembled on the evening of Tuesday, 19 January. The list of witnesses called included the following:

- Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy,

- Private Walter Worswick,

- Private Sandy,

- Private Tutt,

- Mr. Edward Holland (plumber), and

- Mr. Thomas J. Cook (plumber).

The plumbers Edward Holland and Thomas J. Cook had been engaged to examine the ruined boilers and testify as expert witnesses regarding the state of the boilers and cause of the explosion. They testified to the fact that they had found evidence that all four valves, both feed and return on each boiler, had been closed. This, they attributed, was the direct cause of the explosion of each boiler when steam pressure built up in each boiler with no means of escape or the ability to cycle through the system as it was designed to function.

Walter Worswick testified that he had shut the valves when the brothers raked the fires out. Doing so, he stated, was in order to maintain as much heat as possible within the system until it could be restarted again, presumably after William Green had completed his repair work Worswick claimed that he had reopened the valves before restarting the fire. As the boilers heated, he and his brother had heard noises in the pipes and, checking the water flow upstairs, found no hot water being produced. This discovery, and the concerns it raised, led to others being woken with the result of four men being in proximity to the first boiler when it exploded.

Quartermaster Sergeant Dunlevy responded to questions about his responsibility to ensure the men were instructed in the operation of the heating system. He confirmed to the jury that typewritten instructions had been posted in each furnace room. The jury heard evidence from the witnesses until midnight, at which time they retired to consider the evidence and decide upon a verdict.

Twenty-five minutes later the jury returned. The verdict which they brought forward was:

"That the said James Burnett came to his death by being scalded by the explosion of a boiler in connection with the heating of the Military School. We further find the Government to blame in connection with said explosion by not having a competent engineer in charge, as an accident some years ago occurred under similar circumstances by the valves being closed."

No doubt the jury considered that if the recommendations made following the explosion in 1900 had been followed, the conditions for this more recent, and fatal, explosion would not have been possible.

The Survivors; Bernard Dunlevy and Thomas Worswick

Of the four men in the boiler room when it exploded, two survived, each suffering serious injuries and enduring long recovery periods. Both Bernard Dunlevy and Walter Worswick also continued to serve with The Royal Canadian Regiment.

Lance Corporal Bernard Dunlevy

Bernard Joseph Dunlevy was already one of the longest serving soldiers in the London garrison when the boiler accident occurred. He had joined the Infantry School Corps on 11 Jun 1886 at Toronto, over a year before the London company was authorized. Enlisting at the age of 18 years and 7 months, he was 36 years old at the time of the accident. Dunlevy recorded his trade as "labourer" when he joined the regiment, and his place of birth was Sligo, Ireland.

Marrying in London on 9 Jan 1889, Dunlevy and his wife Mary Alice (nee Bass) had six children born between 1890 and 1906. Continuing to serve in London, Dunlevy was discharged to pension on 14 Dec 1912; his rank at the time of his discharge was Quartermaster Sergeant and his character was recorded as "Exemplary." During his service, Bernard Dunlevy would be awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal in 1904 and receive the 1911 Coronation Medal.

The Dunlevy family appears in the 1911 Canadian census for London, Ontario. At that time, they were living on Quebec Street, a short distance east of Wolseley Barracks, with their four younger children (Hazel Theresa, b. 29 Sep 1893; Olive, b. 9 Feb 1896; Bernard Pearson, b. 1 Feb 1898; and Francis Kenneth, b. 30 Mar 1906) Two older children (Myrtle Mary, b. 25 Feb 1890; and William Leonard, b. 31 Oct 1891) had moved out by then. Bernard Dunlevy's sister-in-law and her daughter were also part of the Quebec Street household.

But Q.M. Sergt. Dunlevy's military service did not end with his 1912 discharge. On 28 September, 1914, he re-enlisted for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. His attestation paper, held by Library and Archives Canada, declared 26 years prior service with The Royal Canadian Regiment, and two years with the Army Service Corps. Attesting at Valcartier Camp, he must have been on one of the early trains headed to that location as Colonel Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia, built the CEF for overseas service. When he attested for overseas service, Dunlevy stated that his birthdate was 26 October, 1871, taking about four years off his actual age.

The medical examiner declared that Dunlevy's "Apparent Age" was 42 years, 11 months, leaving him two years short of the upper limit of 45 for enlistment at the time.. With a blonde complexion, grey-blonde hair and blue eyes, Dunlevy stood 5-foot, nine inches, tall with a 45-inch chest measurement. He was noted as having a scar on the inner side of his left knee, but no lasting scar or problem with the foot he had injured in the explosion was recorded. On 14 September, 1914, Dunlevy was pronounced fit for overseas service by Captain Frederick Borden Eaton of the Canadian Permanent Medical Corps.

One of Dunlevy's sons, Bernard Pearson Dunlevy, would also serve in the CEF, enlisting at London on 25 April 1916.

After the war, Bernard Dunlevy would return to Permanent Force service with The Royal Canadian Regiment. An early 1920s group photo of the Sergeants of HQ and "C" Company of The RCR at Wolseley Barracks shows Dunlevy back in uniform with the Regiment. His medal group includes the three ribbons for a First World War trio, his Long Service and Good Conduct Medal and his 1911 Coronation Medal.

Bernard Dunlevy would retire and by 1935, he was living in Riverside, Ontario, and had spent 15 years working an as accountant, and ten living in Riverside where he last worked for the firm of Hiram Walker. It is here, on 22 June, 1935, that he died at the age of 67 years, 8 months.. The cause of death, identified as Myocarditis, inflammation of the heart muscle, was attributed to service causes. His grave registration document shows that Captain Bernard Joseph Dunlevy, Canadian Army Service Corps, was laid to rest in St. Alphonsus Cemetery, Hamilton, Ontario.

Private Walter Worswick

Walter Worswick also continued to serve with The Royal Canadian Regiment. In 1905, the Regiment expanded to provide a battalion headquarters and six new companies to take over the Halifax garrison from the departing British. To offset the challenges of recruiting that many new men at once, drafts of men were also drawn from each of the existing company stations of The RCR to provide a manpower base for the new Halifax garrison.

The 20 July, 1905, edition of The Free Press, published in London, Ontario, stated that Private Walter Worswick would be among the number of men sent from London to Halifax. Recorded as a definitely undesirable service which would last three years, the news article does substantiate the full recovery from the accident enjoyed by Worswick. It notes the he was "one of the leading lights in athletics at the school." The departure of these men was declared by one Sergeant that it would kill nearly every sport in the barracks because of the departure of the barracks' best athletes. Lance-Corporals "Walsh" and "Fitzallen" were also on the list of transferred soldiers in 1905, the former possibly and the latter very likely those who were pallbearers in 1903.

Walter Worswick, by 1914 a Corporal, was still serving with the Regiment in Halifax when he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant on 25 Aug 1914. Shortly after on 1 Sep 1914, and likely a condition of his new rank, Worswick was posted to the new company station of The RCR, "L" Company, at Esquimalt, B.C. It is here that, on 22 Jun 1918, Worswick attested for overseas service at Esquimalt, BC. He was described on his attestation papers as 5-foot 7 1/2-inches tall, with a 38.5-inch chest, a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown and grey hair. Walter was then living at 453 Head St., Esquimalt, with his wife Jane. At an apparent age of 44, he was pronounced fit for overseas service. There was apparently no residual scarring from the 1903 explosion, as he is recorded as having no distinctive marks. Although he transferred to CEF status on this date, Worswick's attestation form wasn't completed until he took his oath on 2 Dec 1918.

On his attestation form Worswick states that he is currently serving in the Permanent Force, and he declared previous service of 4 years, 9 months, with the 1st Volunteer Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. During the years before Worswick joined the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion of The RCR in 1901, the 1st Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers served at Curragh, Ireland (1893-97), in England (1897-99) and then in Malta, Crete and Gibraltar (1899-1902).

Although he transferred to CEF status on 22 Jun 1918, Worswick continued in his duties until 1 Dec 1918 when he was Taken On Strength (TOS) at the Base Depot established for the "Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia)." He was appointed to the Instructional Cadre, a move back-dated to 25 Oct 1918, and promoted to Acting Company Sergeant Major (C.S.M.) effective 1 Dec 1918.

Now belonging to the 16th Infantry Brigade (General Base Depot), Walter Worswick (CEF service number 479931) sailed with the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force (CSEF) from Victoria on 26 December, 1918, aboard SS Protesliaus. Worswick landed in Vladivostock with the CSEF on 15 Jan 1919. Less than a month later, on 4 Feb 1919, Worswick is Struck Off Strength (SOS) of the Base Depot, reverting to substantive rank of Sergeant. Curiously, his service record does not indicate the reason for this change of status.

For his return to Canada, Worswick boarded the S.S. Monteagle on 21 Apr 1919 and arrived back in Victoria on 5 May 1919. The S.S. Monteagle was the second of five troopship voyages that would bring the CSEF back to Canada (the Monteagle would make two of those passages).

Back in Canada, Walter Worswick was TOS No. 11 District Depot, Vancouver, on 20 May 1919 and immediately posted to the Casualty Company in preparation for discharge from the CSEF. In late May or the first week of June 1919, Worswick is medically examined as part of his processing for discharge from the CSEF. The form notes that he has no visible scars, very good sight and hearing and only identified some problems with his joints. The summary of past medical treatment recorded includes:

- 23 Jul 1904, Sinovitis right knee (RCR, London, Ontario) 107 days hospital, good recovery, no trouble since;

- 4 Feb 1909, Gout, 3 attacks (RCR, Halifax), gave up alcohol, and has had no trouble since;

- 29 Jun 1915, Rhuematism, 15 days, no trouble since; and

- He has no disability now

Curiously, even though his lengthy hospital stay starting in July 1904 is mentioned, the injuries he sustained in the boiler explosion in December 1903 are not listed.

Worswick's discharge in Jun of 1919 is postponed and he is transferred to No. 11 Artillery Depot on 6 Jun 1919. He remains here until reverting to the District Depot on 28 Nov 1919. After which he is attached to No. 5 Company, RCGA, the Permanent Force garrison artillery at Work Point Barracks, Esquimalt. On 14 Jan 1920, Worswick's promotion to Company Sergeant Major, back-dated to 1 Apr 1919, is recorded.

It is not until 6 Jun 1920 that Walter Worswick is finally Struck off Strength of the CSEF for purposes of Demobilization. He remained at Victoria after his discharge.

Walter Worswick died 10 Feb 1943 at the age of 68. He is buried at the Veteran's Cemetery in Victoria. His gravestone, which indicates he ended his service with the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, reads:

In Loving Memory of

Q.M.S. Walter Worswick

P.P.C.L.I.

Born in England March 27, 1875

Died February 10, 1943

Rest in Peace

Mount Pleasant Cemetery

Established in 1875, Mount Pleasant Cemetery in London, Ontario, is one of the city's oldest and largest cemeteries. Divided by winding asphalt roadways into many discrete sections, the general flow of the cemetery's growth, and the average affluence of those in each section can be traced by the changing dates and sizes of the headstones.

In Mount Pleasant Cemetery, James Burnett and Thomas Worswick were laid to rest in what is now one of the older sections, labeled "Q" on the cemetery's current maps. They are in graves numbered 491 and 492 of this section. Section "Q" is covered with healthy lawn between the gravestones, of which many stones are noticeably absent once a visitor realizes that each burial plot is only three feet long and eight feet wide (less than 1 metre by 2.5 metres).

The list of graves numbered from 470 to 500, bracketing those of Burnett and Worswick, include four identifiable stones at 470, 471, 475 and 478. From these it is possible to pace off the rest of that row to #488, where the plots abut a section for the "Aged People's Home" and reverse direction to form the next row. A few more strides carry the visitor to the open grassy area where the graves of these two Royal Canadians lie side by side.

No stone or marker identifies the graves of James Burnett or Thomas Worswick at the time of this writing. Stones were not provided by the Militia Department in that era, and in their cases, neither family nor comrades paid for stones to be set in place.

These two soldiers of The Royal Canadian Regiment rest quietly in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, all but forgotten by their Regiment, by the Army, and by their nation. James Burnett or Thomas Worswick, having died of injuries sustained in the performance of their duties, do not deserve to lie in unmarked graves.

Circled camera bag shows location of graves.

Author's Note: Summer 2014 inquiries with Mount Pleasant Cemetery confirm, that a standard "soldier's gravestone," including installation, costs approximately $2100.

Pro Patria

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

![]() Too Few Honours; Rumours of Historical Parsimony in Regimental Honours and Awards

Too Few Honours; Rumours of Historical Parsimony in Regimental Honours and Awards

![]() The RCR and Historic South-Western Ontario Units

The RCR and Historic South-Western Ontario Units