Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

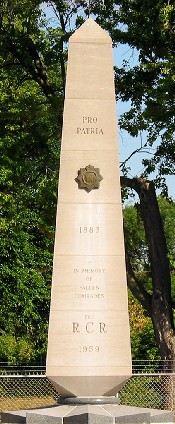

The Regimental Memorial of The Royal Canadian Regiment, located at Wolseley Barracks in London Ontario. Wolseley Barracks has been the home of the 1st and 2nd Battalions and the Regimental Depot. Wolseley Barracks remains the home of the 4th Battalion and the Regimental Museum.

CAP BADGE

1922 Alta Vista Drive

Ottawa, Ontario

KIH 7K6

9 May, 1977

Colonel A.S.A. Galloway, ED, CD

Pro Patria Issue No. 33, August 1977

Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, The RCR began to take on reinforcement officers from the militia. I was one of the first, joining on the same day as George Hungerford, Beverley Howey and Don MacLennan. all three of whom are now dead, the former having been killed-in-action with the Regiment at Rimini in September 1944. At Wolseley Barracks the Depot was commanded by Major "China" Neilson, DSO, with Lt. Harvey Bonner as Adjutant and Lt. "Tug" Wilson as QM, CQMS (later Major) F.G.W. Pannell, but back in 1935 my batman at a Royal School, was in the stores. All four of these one-time Regimental characters are now also dead.

Arriving as militia officers, the first thing we wanted to do after being sworn in as CASF officers on the RCR list was to put up our new cap badge, beavers and shoulder titles. We were especially proud to wear the RCR eight-pointed star, surely the handsomest cap badge ever worn in the Canadian Army. Unfortunately, officers' cap badges were not obtainable and we had to make do with out-dated issue badges bearing the Hanoverian crown. rather than the St. Edward's crown. I continued to use this badge on my fore-and-aft up until February 1943 when in North Africa, on of all days, Paardeberg Day, my kit bag was robbed by the Royal Irish Fusiliers, when they took over an Arab farm which I and my London Irish Rifles friends had temporarily vacated during a see-saw battle with the Hermann Goering Jaeger Regiment.

But going back to the beginning. Officers' pattern cap badges soon became available and despite the issue one I wore on my FS cap. I naturally wore the proper one on my cap NP.

One thing we certainly gloried in was a well-shone cap badge. I suppose everyone still does, but I'm told they are permanently shone now, and neither one's own, nor one's batman's elbow grease is now necessary. My excellent batman, Pte Harry W. Armitage, always kept my badge shining like the sun in its full glory -- it mattered not for what, walking out, parades or even on the battlefield. One of the last things he did on the night of July 9th/10th, 1943 was to shine my cap badge for me. Next morning the hot sun of Sicily made it sparkle like the Kohinoor diamond.

But if I took the pleasure, it was Harry who took the blame. I had picked him as my batman back in 1942 because he did not want to become an NCO, but was willing to be my unofficial "adjutant" as well as my batman. He could read a map, convey intelligible messages and kept his thumb on the pulse of the rank-and-file. He could dig a deep slit trench, cook a meal and always find the RV.

If it were to be a choice between losing a rifle section or Pte Armitage, I would have kept Armitage. His value to me and therefore to my Company was that much.

However, shining my badge as part of our "preparation for battle" became a sort of self-inflicted wound for Armitage. This is how it happened. At Valguarnera, our first real action of the Sicilian campaign, I was ordered forward to make a reconnaissance for an attack we were to put in. I summoned Armitage, showed him an RV on the map and told him to lead the Company up to an assembly area, then bring the three platoon commanders up to the RV where I would issue my orders.

Armitage carried out my instructions to the letter. In due course he reported to me on the top of a hill, the three subalterns behind him. We crouched behind some boulders and I outlined the plan of attack, gave the necessary administrative instructions, "zero hour" as we still called it in '43', and then sent them back to bring their platoons forward to the FUP. Next, I shouted to Armitage to come forward and together we crawled up to the crest of the hill. We arrived behind a hedgerow of sorts and a few scattered boulders. (The sun shone down on us in midday fury out of a bright blue sky. We were dry and dusty. Our equipment tugged at our shoulders and our sun-burned knees smarted in the heat. We squinted across the rock and cactus-strewn valley to the distant ridge shielding the town of Valguernara, which was our objective. The intervening ground lay dusty below, the shimmering heat waves of summer in Sicily.

The heavy sweet scent of parched vegetation mingled with the putrid stink of goat dung and decomposing animal flesh. But the battlefield was almost silent. Only a few wisps of curled up from encampments the retreating Italians had set afire a day or so before. Only a few thuds and geysers of black smoke could be seen or heard where the odd German or Canadian mortar bomb searched what looked like an empty landscape.

We crept closer to the hedgerow. Parting a few branches gingerly, I looked toward enemy territory. With my stick as a pointer I indicated the line of advance of each platoon and as much as possible where their objectives would be. Armitage nodded that he understood. As a personal messenger between me and my platoon commanders he had to know these things. If I became a casualty, he had to be able to tell my successor where everyone was, or at least was supposed to be. I then gave him the last bit of information necessary.

"When the platoons pass this line, I will join the right forward platoon to help Mr Sims do a right flank around that hill. Got it?"

"Sir", replied Armitage, meaning that the message was understood.

"Now go and b ring the CSM and Company, Headquarters up and have them follow the right platoon. Join me on that hill as soon after we cross the Start Line as you can. Okay?"

"Sir", replied my good and faithful servant, indicating that he understood and would carry out my order.

For a moment we lay together, while he once more checked no-man's-land with his sun-seared eyeballs. I parted the hedge slightly to help him get the broadest possible view. It was then that it happened.

I heard a gasp. Then a sound like bubbling water. I looked at Armitage. He was grasping his throat, a glazed look on his eyes. Rich, almost purple blood was gushing out between his fingers. He had been shot right through the throat!

The bullet which must have been meant to knock my shiny cap badge in between my eyes had hit Armitage instead. The Jerry sniper could not shoot as well as Armitage could shine. In shooting language, he only scored a magpie.

Armitage survived the war and is living today. The attack went in and was successful, with less than a dozen additional casualties.

The other day I was looking at my cap badge. It is in a box in my desk drawer. The silver VRI is practically worn away. It isn't shiny anymore. It's a long time since the war, a long time since the heat of Sicily and the snipers' bullets—and a long time since my cap badge shone on the hill at Valguernera. I was proud of my shiny cap badge then. How often pride is only folly.