Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

Badge worn by the Second (Special Service) Battalion of The Royal Canadian Regiment while serving in the South African War; 1899-1900.

In South Africa with The Royal Canadian Regiment

Dr. A.S. McCormick

Reproduced from Pro Patria, Issue No. 25, Aug 1975

The year – 1900

In South Africa there were almost no roads and the army moved en masse across the veldt. When we passed-over a ridge or hill we could see cavalry, mounted infantry, horse artillery, and field artillery far ahead raising dust. Following them and as far as we could see on both sides and behind us countless infantry battalions.

The rocks were hard on boots, many of which fell apart. The men were unshaven, lousy, uniforms in rags. Except when in garrison, none shaved--they were too tired at night and water was too scarce. The men were terribly thirsty and drank from frog ponds, dirty pondsanything to get water. The order was "all water must be boiled". But after marching all day in the hot sun drinking all the water in your bottle, who would have the patience to boil the water, then wait all night until it cooled by morning.

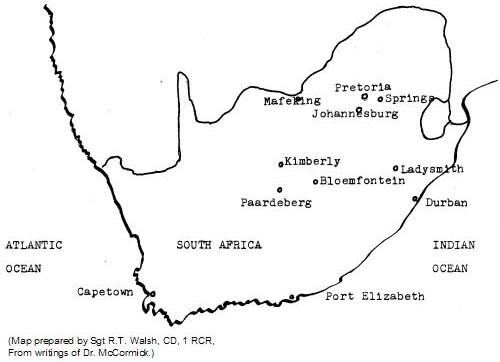

Bloemfontein was entered March 15th and the army halted to rest and obtain supplies. When orders were received to proceed to a nearby town and carry only bare necessities because "we will return in three days" the orders were obeyed. Three days lengthened to seven months before the battalion saw Bloemfontein again. Such is the uncertainty of war.

The SCR carried the 55 pound Oliver equipment (overcoat, bandolier with 100 rounds, Lee Enfield rifle, 9 pounds, ball pouch with 50 rounds, water bottle, canteen, bayonet, haversack), an equipment very hard on the men who damned Surgeon Oliver who designed it.

The air was clear and in the summer (winter in Canada and U.S.A.) the days were bright and warm. On the march, we spread out to let the air get between us. After one experience sleeping in a cold sweater, I learned to put my sweater on under the tunic and. carry my flannel shirt. When we halted for the night, I put on the dry shirt. Some idea of how cold the nights were you may realize when I say that I put on my sweater, cardigan jacket, on the ground my rubber sheet and overcoat, then the blankets arranged in four layers and even with all this I was sometimes cold. And, of course, we slept on the hard ground.

Pretoria surrendered in June. The march past before Lord Roberts as the troops entered the city was a great spectacle.

From Pretoria, we went to Springs to guard the coal mines. After a "sentry go" of 24 hours, men were black from the dust. This was the only place where we lived in buildings. The remainder of the time, except for an occasional short period in which we had tents, we lived in the great outdoors in days hot and nights freezing cold. It is a healthy climate and none ever caught cold.

Around the town were outposts with trenches where sentries were posted. It wasn't bad during the day, but the nights were so very dark that it was impossible to see more than 10 feet. A sentry watched less for the enemy than for the officer making his rounds, for if he failed to see and challenge him he got hell. One hour before daylight the battalion with loaded rifles fell in at the square to ready for a night attack. What is called "night attack is actually an attack at daybreak and we were ready. One night an alarm called us out because "heavy firing has been heard at No.8 outpost". A company hurried over and learned that there had been no firing. Later it was discovered that a Kaffir mule driver had drawn the end of his whip along the side of a corrugated iron house as he passed and the rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr sounded to the main guard sentry like distant rifle fire. At another station, Silverton near Pretoria, every day at the hour of noon when "come to the cookhouse door, boys" was sounded, a sandstorm arose. We had to run into the tents and close every opening to keep the sand from getting into the food.

August 2nd we left Springs for the Orange Free State to join a brigade and go after DeWet, the most clever guerilla. We did not catch him, but we gave him the run of his life and in 21 days drove him to the far north of the Transvaal, although we were on foot and his men on horses. On the 10th we crossed the Vaal River from the O.F.S. into the Transvaal. The river at this point is 500 to 600 feet wide and we accomplished the almost incredible feat of crossing without getting wet.' At high water the river is a raging torrent. When we crossed it was low water but even so just as wet and there were many deep pools. We crossed by jumping from rock to rock. At dangerous spots, two men stood where they could catch the jumper as he landed. Only one man fell in. The British officers were not as adaptable to the situation as were ours and the men of the other four battalions splashed their way across with no chance of getting dry because the march, like a show, must go on. The other battalions in the brigade which were commanded by Major General Fitzroy Hart were the 1st Battalion Derbyshire Regiment, 2nd Battalion Dublin Fusiliers, 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry, and 2nd Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers.

Marching day and night with only four hours for sleep, we averaged seventeen miles per day and did 301 miles in 20 days. One day I went on sentry-go at midnight. The march started at 2:30 and we did not stop until 11:30 during which time I was still on sentry-go by the water cart, a record sentry-go of eleven and a half hours. We marched 30 miles, the last four hours under a hot sun, up and down hills. When we finally halted, men of all the battalions straggled in for two hours, dropped everything and lay down. After four hour$ we resumed the march but were turned back after going two miles. Then we learned that we had been on the way to relieve besieged Zeerust near Mafeking but that another force had reached the place.

One day when some careless boob in the mounted infantry ahead dropped a lighted match we had to run like hell to get around the blazing dry grass. Food was short; weak coffee and biscuits for breakfast, tea and biscuits at noon; for supper thin soup, some boiled meat, tea and biscuits. Very monotonous.

In spite of everything the men of the RCR were a jolly lot and saw the humour in any difficulty. On the march a group of 24 singers marched in the middle of the battalion and sang. Two popular songs were the lovely "Blow Ye Winds in the Morning" and "I'll Make Dat Black Gal Mine". When a French Canadian member of F Co. would start a French song his company and E Co. joined in.

We left the brigade at Krugersdorp and moved by train to stations on the Delegoa Bay Railroad.

October 24th we marched to Pretoria, arriving shortly before the darkness which comes in only a few minutes.

We had no tents and the night was very unpleasant sleeping on the ground in a wild rainstorm. After two days in Pretoria, we left for Capetown; the officers in comfortable coaches, the men in open coal trucks. Bully beef, biscuits, tea -- very tiresome and unsatisfactory.

We reached Capetown November 7th and immediately boarded the Elder-Dempster S.S. Hawarden Castle which sailed at 4:00 p.m. Also on board was the Household Cavalry Regiment, a fine lot of men.

On the voyage we passed through the Canary Islands and Madeira. We had 24 hours at St. Vincent in the Cape Verde Islands. We arrived at Southampton on the morning of November 29th and were in London in the afternoon. The London streets were lined with cheering crowds as the band of the Coldstream Guards led us to Kens1ngton Barracks. We had comfortable quarters and nice meals, but on the first night in a bed after so many months sleeping on the ground many of us could not sleep. Some rolled up in blankets and slept on the floor.

December 10th we left for Liverpool, arriving in the early afternoon. The streets were lined so that we had barely enough space to march. The huge square by the law courts and town hall was packed with at least 50,000 cheering men and women.

We sailed on the 'Lake Champlain' December l2th, stopped at Queenstown, Ireland, on the l3th, reached Halifax on the 23rd and I was home the afternoon of the 24th. We got out at our stations in full marching order with our entire equipment which the Government decided we should be allowed to keep.

The Canadian Government gave us scrip for 320 acres in Western Canada. I sold mine for $700.00.