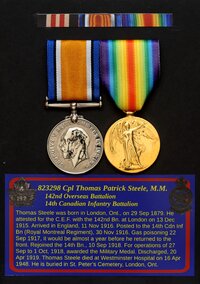

823298 Pte Thomas Patrick Steele, M.M.

142nd Canadian Overseas Battalion

14th Canadian Infantry Battalion

By: Capt (ret'd) Michael M. O'Leary, CD, The RCR

Thomas Patrick Steele was born in London, Ont., on 29 Sep 1879. He was the second of eight children born to Thomas Steele and Eliza Bray between 1877 and 1894. The family appears in the 1891 Canadian census of London. Led by parents Thomas (48) and Eliza (36), there are six children in the home: Joseph H. (15), Thomas P. (12), John (10), Maud (7), William (5), and Henry (2).

In the 1900 edition of a London city directory, Thomas P. Steel (sic), labourer, is shown to be living at 184 Maitland St., London, Ont. Also living at the address were Eliza (widow of Thomas), John J., and Joseph H., with both brothers having their trade shown as labourer.

Steele also appears in the 1901 Canadian Census. At the age of 23, he is shown in a family group with Mary A. Steele (31) and children Annie L. (age 7, b. 25 Dec 1893), Francis P. (age 4, b. 18 Nov 1896), and Thomas J. (age 1, b. 29 Sep 1899).

The Baptismal Register of St. Peter's Cathedral, City of London, has an entry dated 5 Apr 1901 for the baptism of Thomas Joseph Steele. The entry, signed by J.T. Aylwood, Priest, reads: "I, the undersigned, have baptized Thomas Joseph, born in London on Sept. 10th, 1899 from the lawful marriage of Thomas Steele of London and May Ann Selby of London."

Searches for the other two children in the household reveals a complex family story. "Annie L." appears in the Baptismal Register of St. Peter's Cathedral, City of London. Her entry, dated 29 Mar 1894, reads: "I, the undersigned, have baptized Anny Louisa, born in London, Ont., on Dec. 16th, 1893 from the lawful marriage of Mr. Bert Simpson of London and May Ann Selby of London" was signed by M. McCormack, Priest. Francis Paul appears in the birth records for Essex County. He was born 18 Nov 1896, and is identified as the son of George Munroe, a Windsor basket maker, and Mary Ann Selby.

Digging deeper into Mary Steele's story reveals that she married Alfred Garner, a farrier and horse trainer, at London, Ont., on 24 Dec 1885. Mary is shown in the 1891 Canadian census living with her mother Catherine and brother Thomas. Also in the household is 5-year-old Ella May Garner. Searches for later appearances of Alfred or Ella Garner have led to no confirmed connections for their fates. There is also no clear evidence of what happened to Bert Simpson or George Munroe before Mary began sharing her household with Thomas Steele by 1898-99, i.e., before the birth of Thomas J.

Thomas and Mary's daughter Gertrude Hazel was born in London, Ont., on 23 May 1902. She was baptized at St. Peter's Cathedral on 10 Jul 1902.

The Steele family appears in the 1911 Canadian census. Mary (42) and Thomas (32) are shown with six others in the house. These are Frank (15), Thomas (11), Hazel (9), Thomas' brother Harry ("Henry," 22), Pearl (17, Harry's wife), and Ella (2). Steele's trade is given as malster (i.e., maltster, or brewer) and son Frank was working as a cigar maker. Pearl was also working in the cigar trade and Harry was a labourer.

Thomas Steele attested for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (C.E.F.) with the 142nd Overseas Battalion at London, Ont., on 13 Dec 1915. A 36-year-old labourer, he was described on his attestation paper as 5 feet 5 inches tall, weighing 142 pounds, with a 35 1/2-inch chest, a ruddy complexion, blue to grey eyes, and dark brown hair. His religious denomination was Roman Catholic. Steele identified his wife, Mary Steele, 17 York St., London, Ont., as his next of kin. On attesting with the 142nd Battalion, Steele was given the service number 823298.

On 27 Jan 1916, events in Steele's life took place that also helps to untangle the story of his family situation. On that day, Thomas Patrick Steele (age 36), bachelor and labourer, originally of Ingersoll, Oxford County, married Mary Garner (age 45), widow, of London, Ontario, where she had resided since the year 1899. Their marriage, probably solemnized to ensure Mary's entitlement to Separation Allowance once Thomas left the country with the C.E.F., confirmed that although they had been living together for years as husband and wife, they had not been married. Notably, the marriage certificate also shows that Mary's legal surname was that of her first husband, establishing that her other children had been born out of wedlock despite being recognized as legally married for their respective baptisms.

Steele's battalion, the 142nd (London's Own) Battalion, C.E.F., was based in London, Ont., where the unit began recruiting in late 1915. After sailing from Canada on 1 Nov 1916 aboard the S.S. Southland, the battalion was absorbed into the 23rd Reserve Battalion, C.E.F. on 11 Nov 1916 when it arrived in England.

Commencing November, 1915, Steele established a monthly Pay Assignment of $20 to be sent to his wife. As a Private in the C.E.F., Steele was paid $1.00 per day plus an additional ten cents daily field allowance. His pay assignment represented about two-thirds of his monthly pay. Mary Steele also received $20 monthly Separation Allowance, which began in March, 1916. The amount of separation allowance would increase to $25 per month in December, 1917, and to $30 in September, 1918.

The day after landing in England, 12 Nov 1916, Steele was taken on the strength of the 23rd Reserve Battalion. The 23rd Res. Bn. was formed as the 23rd Overseas Battalion on 6 Aug 1914 and mobilized at Quebec City. The battalion sailed for England on 2 Feb 1915 and on 29 Apr 1915 was re-organized as the 23rd Reserve Battalion. Receiving troops from units arriving from Canada, the 23rd Res. Bn. formed reinforcement drafts for France for the remainder of the war.

On 30 Nov 1916, less than a month after arriving in England, Steele was drafted to the 14th Canadian Infantry Battalion. The 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment) was authorized on 1 Sep 1914 and embarked for The UK in late September, 1914. The unit disembarked in France on 15 Feb 1915 as a battalion of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade in the 1st Canadian Division.

Steele arrived at the Canadian Base Depot (C.B.D.) at Le Havre, France. on 1 Dec 1916. Two weeks later, on 16 Jan 1917, he left the C.B.D. for the 1st Entrenching Battalion. This Divisional troops unit was employed as a ready labour force and by design its troops were a forward reserve of reinforcements for the division's fighting battalions. They were used as labour forces to maintain and build trenches or other work as needed. The 1st Cdn. Entr. Bn. was organized at the C.B.D. in July 1916 and was disbanded in September 1917 on formation of Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp.

Joining the 1st Cdn. Entr. Bn. in the field on 20 Jan 1917, Steele remained with the unit for a little more than two months. On 28 Mar 1917, he left the entrenching battalion for the 14th Battalion and joined the unit the same day.

Steele arrived at the 14th Battalion as the unit went into Divisional Reserve at Pendu Huts after conducting a trench raid early that morning. The battalion would return to front line trenches on 6 Apr 1917. Seven times between early April and late September, the 14th Battalion would occupy forward trenches. During these months, Steele would experience the front line trenches, support trenches, reserve positions, marching, and training that were the perpetual cycle of the infantry battalions on the Western Front. Each step in this steady rotation of positions and battlefield roles was usually about 4-5 days, though longer periods could occur. Few tours of the front lines were without casualties, and even when out of the most forward trenches, the reach of enemy artillery could take its toll.

Re-entering the forward lines on 16 Sep 1917, the regimental history of the 14th Battalion, C.E.F., by R.C. Fetherstonhaugh (1927) details the gas attack on the unit in September, 1917, while in Brigade Reserve:

"Following the religious exercises on the morning of September 16th, the men of the Battalion rested until evening, and then marched to Cité St. Pierre to relieve the 138th Canadian Battalion in Brigade Reserve. Working parties of 7 officers and 350 men were supplied to the Engineers on several occasions during the tour that followed. Casualties were light until the early morning of September 21st, when the enemy bombarded with high explosive and gas. One gas shell burst within a few feet of the sentry at No. 4 Coy's. Headquarters and choked him before he could sound the alarm. Similar shells followed, their vapour flooding the H.Q. dugout and gassing a number of men within. High explosive then struck the billet of the Battalion Pioneers, tearing away the protective blanket and exposing the men to the full effects of gas shells which followed a moment later. The suffering of the men caught by the barrage of phosgene and mustard gas was severe. Temporary blindness followed in several eases, and over 60 men were evacuated with badly irritated throats and lungs. Officers also suffered from this shelling and several were badly gassed, … The concentration of gas on September 21st was not dissipated for many hours, the troops being forced to wear gas helmets throughout the day.

"At 11 p.m. on September 22nd the enemy once more bombarded Cité St. Pierre with phosgene and mustard gas, continuing to deluge the area until after 3 o'clock on the following morning. All working parties were accordingly cancelled and the men held as much as possible inside the protection of gas-proof dugouts. At night the Battalion was relieved by the 1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, and marched back to Marqueffles Farm, reaching this position on the morning of September 23rd and proceeding at 5.30 p.m., via Bouvigny-Boyeffles and Petit Servins, to Grand Servins, and thence by cross-country trail to Corps Reserve in Estrée Cauchie."

After a period in Corps Reserve, the 14th Battalion returned to Brigade Reserve in the Zouave Valley on 5 Oct 1917 and relieved the 44th and 47th Battalions in the line that night. Steele was not with them, the effects of the September gas attack having taken their toll. Steele's medical records show that he spent the next five months in medical care for a "slight" case of gas poisoning that did not have immediate effect and took two weeks to incapacitate him. It was almost a year before he returned to the front.

On 5 Oct 1917, Steele was admitted to No. 6 Casualty Clearing Station (C.C.S.) suffering from gas poisoning. Two days later, he was transferred to No. 7 Canadian General Hospital, at Chateau d'Arques, France. After another week in hospital, on 14 Oct 1917, Steele was invalided to England, evacuated across the Channel aboard the hospital ship H.S. Ville de Liege, and transferred to the Richmond Military Hospital, Grove Road, Richmond, London.

On arriving at Richmond Military Hospital, Steele was examined on 14 Oct 1917 to determine his condition on admission. The case notes from this exam read: "Gassed on 20 Sept. Symptoms of soreness of throat and chest developed several days later. Stomach and eyes also slightly affected at first. Present state – some conjunctivitis, dry cough, no expectoration. Fauces injected. On examination, poor respiratory movement with an occasional rhouchus (i.e., a whistling or snoring sound)."

On leaving the continent, Steele was struck off the strength of the battalion and posted to the 1st Quebec Regimental Depot (Q.R.D.). The 1st Q.R.D. was part of the new (as of March, 1917) regionally based reinforcement system, with named Depots taking in troops from battalions raised in those areas in Canada and providing reinforcement drafts to similarly designated fighting units. The 14th Cdn. Inf. Bn., having been originally formed in Montreal, was associated with the 1st Q.R.D. These Depots also became the parent unit for any soldiers returned to England from their affiliated battalions in France and Flanders. (Steele and the 142nd Bn. arrived overseas before the institution of the regional reinforcement system. That is why he and other South Western Ontario soldiers from his unit of enlistment ended up in a Quebec battalion and subsequently under the Q.R.D.)

Ten days after his first admission to the C.C.S., The London Advertiser published a brief list of casualties from the district on 15 Oct 1917. The list included: "Gassed: London, 823298 T.P. Steele."

Steele's medical case notes detailed the progress of his recovery. The slow progression of his condition was that experienced by soldiers who were considered to have a mild case of gas poisoning, one that did not immediately incapacitate him at the time:

- 19 Oct 1917: "Cough much better, eyes better, general improvement all around."

- 22 Oct 1917: "Eyes, chest and abdominal pain much better."

- 26 Oct 1917: "Still makes dry cough with complaint of shooting pains through chest. Expectoration nil."

- 2 Nov 1917: "Some worsening of bronchial state, general improvement. Eyes now practically clear. Fauces, some injection still."

- 7 Nov 1917: "Cough still troublesome, ?? still some injection of fauces."

- 9 Nov 1917: "Recommended for discharge to Canadian Convalescent Hospital."

- 12 Nov 1917: "Present Condition – Has tight cough and slight photophobia."

By 12 Nov 1917, Steele's condition was considered improved enough for transfer to the 500-bed capacity Canadian Convalescence Hospital at Hillingsdon House, Uxbridge. He was duly passed to this facility and the notes recorded at the time of his transfer stated "Still has cough."

During Steele's hospitalization, telegrams were sent to his family to inform them of his condition. On 11 Nov 1917, the first cable read "Mil. Hosp. Richmond, suffering from gas poisoning." Two days later a second cable followed "Doing very well, Can. Conv. Hosp., Uxbridge, Kent."

At the Canadian Convalescence Hospital in Uxbridge, the detailed recording of Steele's condition continued:

- 19 Nov 1917: "Cough is sharp and irritating."

- 29 Nov 1917: "Cough some improved."

- 11 Dec 1917: "Still has bad cough. Transferred to Epsom."

On discharge from the Convalescent Hospital, Uxbridge, Steele's case notes read: "Still has cough. Transferred to Manor War Hosp., Epsom." This transfer was caused by the Uxbridge property being taken over by the Air Ministry and Hillingdon House closing as a medical facility.

On 12 Dec 1917, Steele was admitted to Manor City of London War Hospital, Epsom. Case notes at Manor War Hospital, dated 6 Jan 1918, read: "Admitted here convalescing from gas poisoning. Complains of indigestion and pain in epigastrum. Nothing abnormal found in abdomen. Lungs negative. Heart negative. Should be fit for active service within six months. Transferred to Woodcote."

Steele was admitted to the Military Convalescent Hospital, Woodcote Park, Epsom, on 15 Jan 1918. His Medical Case Sheet noted his condition: "Disease, Gas Poisoning. Gassed in Sept. Chief Complaints – Pains in stomach, chest and eyes, cough, but no expectoration. Has been having indigestion since Sept. Physical Examination – Eyes inflamed. Lungs show rales at both apicies and over bases. Heart negative." By 23 Jan 1918, his case notes read: "Complains of pains in belly. Gram. neg. Has done P.T.!! here. 23.1.18 Fit for D 1/1." (The latter is likely a notation for the medical category subgroup for "other ranks of any unit under medical treatment, who on completion would rejoin their original category.")

On 28 Jan 1918, Steele was discharged from hospital and placed "On Command," a temporary assignment without change of parent unit, to No. 2 Canadian Convalescent Depot (C.C.D.), Bramshott. This was a facility where soldiers could recover from wounds and rebuild their strength. Three weeks later, on 22 Mar 1918, Steele ceased to be attached to 2 C.C.D. on return to the 23rd Res. Bn. where he remained for over five months.

Almost a year after his evacuation from France for gas poisoning, Steele joined a new reinforcement draft for France on 5 Sep 1918 and was returned to the 14th Battalion. Moving quickly through the rear areas, he arrived at the C.B.D. on 6 Sep 1918. Three days later he passed through the Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp (C.C.R.C.) and rejoined the 14th Battalion in the field on 10 Sep 1918.

The 14th Battalion was in Billets at Berneville from 4 to 19 Sep 1918. After suffering losses of over 250, killed, wounded, and missing, in the fighting at the Drocourt-Queant Line during 2-3 Sep 1918, the unit was in need of a chance to absorb reinforcements and reorganize.

Marching out of Berneville on 19 Sep 1918, the 14th Bn. moved into old trenches at Telegraph Hill for a few days. They moved again on 24 Sep 1918, marched to Arras, then entrained to Bullecourt. Another march took the unit into the forward lines, relieving the 18th Battalion in Buissy Switch on the night of 25 Sep 1918. This was to be the assembly position in preparation for the Battle of the Canada du Nord and the battalion's role in the Capture of Bourlon Wood.

After spending the 26th making arrangements for an attack, the 14th Battalion, supported by tanks, jumped off at 5.20 a.m. on 27 Sep 1918. The unit War Diary records the actions of the day:

"BUISSY SWITCH – Sept. 27th

"There was considerable gas shelling on the way in, but no casualties. The 16th Canadian Battalion were holding assembly area, but were not very familiar with ground, as they had taken ever from the 2nd Division only the night before, The 16th Battalion rendered valuable assistance during our assembly, and left a platoon in PAVILAND WOOD to deal with a machine gun nest. Posts were established to cover assembly ma the area reconnoitred; Dykes and several rows of wire were discovered at the eastern edge of the wood. Information received from the Intelligence regarding this area proved to be very inaccurate. Bridges and rafts to be used in crossing the canal and dykes did not arrive.

"The Battalion attacked at dawn. Objectives, CANAL DU NORD, SAINS LEZ MARQUION, and trench system to the east, The barrage opened at 5.20 a.m, and the Battalion began the attack of the famous CANAL DU NORD and MARQUION lines, The Canal was crossed at 5.45 a.m., and the attack was well launched, both officers and men did wonderful work, Recommendations are submitted for officers and men who particularly distinguished themselves. The final objective was reached at 7.30 a.m., and the Battalion consolidated on a two-company frontage."

The cost to the battalion was heavy, with the Commanding Officer's report in the War Diary noting over 200 killed, wounded, and missing. In balance, the 14th Battalion captured approximate 50 German machine guns, a number of trench mortars, and an anti-tank rifle in addition to 450 prisoners of war.

Four days later, on 1 Oct 1918, the 14th Battalion went over the top again in another assault on German positions.

"SOUTH-WEST of CAMBRAI-DOUAI RD. Near SAUCOURT – Oct 1st.

"The 14th Canadian Battalion assembled in depth on a one Company frontage immediately south west of the CAMBRAI–DOUAI Road facing the village of SAUCOURT. The assembly was made under very unfavourable circumstances, It rained heavily during the night, and the country in vicinity of the assembly area was a maze of mud, shell-holes and wire. There had been no opportunity for a preliminary reconnaissance and the guides had lost their way. Notwithstanding those difficulties the assembly was completed in good time. Waiting for ZERO is always very trying, still, despite the rain, cold and the fact that there was no rum issue, the spirit of the men was excellent. The Battalion attacked at 5.00 a.m. with 13 Officers and 375 other ranks."

A lengthy and detailed report by the Commanding Officer attached to the War Diary for the month of October, 1918, describes a costly, confusing and ultimately unsuccessful assault by the 14th Battalion. Despite the best efforts of all ranks, losses of means of communications and artillery support compounded the problems of losses throughout the units chain of command and stymied efforts to gain and hold ground. By the end of the day, platoons and companies in the unit were led by non-commissioned officers, from the few remaining to fill those roles. The C.O. noted in his report:

"Too much cannot be said in praise of the Non-Commissioned Officers who so successfully handled their platoons, and in two cases, companies throughout the entire day's operation, but unfortunately in rendering these excellent services many of them have become casualties."

The 14th Battalion left the Cambrai area on 5 Oct 1918 to the Viz-en-Artois area. Four days later, on 9 Oct 1918, Steele was sent On Command to the C.C.R.C. While at the reinforcement camp, he was appointed Lance Corporal on 15 Oct 1918.

On 23 Oct 1918, the 14th Bn. moved into billets at Fenain. The battalion would remain here until the end of the war. Steele's name appears in the battalion War Diary during this period. On 10 Nov 1918, the day before the war ended, the War Diary entry included:

"The following decorations were awarded to the undernoted other ranks of the battalion for gallant conduct in the field, in the operations of Sept. 27th to Oct. 1st, 1918."

"Military Medal – 823298 Pte. Steele, T.P.

Steele returned "Off Command" to the 14th Battalion on 17 Nov 1918. Three months later, on 14 Feb 1919, while the unit was at Huy, Belgium, he was promoted to the rank of Corporal

On 14 Mar 1919, after a week at Le Havre, the 14th Battalion began its journey back to Canada. The War Diary notes:

"LE HAVRE – March 14th.

"The Battalion paraded at 1300 hours at very short notice and marched to the wharf, embarking on the S.S. QUEEN ALEXANDRA about 1500 hours. Owing to shortness of notice a few men were left behind and the Battalion embarked 30 Officers and 653 Other Ranks. The ship sailed at 1620 hours (French time). The weather was good and the Channel comparatively smooth. Anchored off WEYMOUTH at 2300 hrs. (English time)

"BRAMSHOTT – March 15th.

"The S.S. QUEEN ALEXANDRA moved into the quay at 0900 hours and the Battalion disembarked immediately and were served with a hot meal. Before entraining each man received a bag containing a substantial cold meal. The Battalion left WEYMOUTH at 2100 hours arriving at LIPHOOK about 1500 hours where hot tea and cakes were served. After a short march BRAMSHOTT CAMP was reached, the Battalion being allotted to "D" Wing in the south part of the Camp. A hot meal was in readiness and everyone soon settled down in their new quarters. From the time of landing in WEYMOUTH to settling down in BRAMSHOTT the Battalion was handled expeditiously and with every regard to the men's comfort and well being. Nothing but the highest praise can be given to those in charge of the arrangements."

The battalion's last War Diary entry was recorded on 9 Apr 1919:

"BRAMSHOTT – April 9th.

"The official orders for the embarkation of the Battalion on the S.S. CARMANIA to-morrow were received with keen delight by all. The Battalion is to parade at 2330 hrs. to-night, entraining at 0120 hrs., breakfast is to be had at CREWE at 0820 hrs. and it is expected to reach RIVERSIDE at 1000 hrs. where embarkation is to take place immediately. Everything possible is being done to make the trip as comfortable and enjoyable as can be. Needless to say all ranks are eagerly looking forward to the arrival in Montreal of the Royal Montreal Regiment after so long an absence from their native heath."

Steele, along with others in the battalion, were taken on the strength of No. 4 District Depot, Montreal, on sailing from England. He disembarked at Montreal on 18 Apr 1919 and two days later, on 20 Apr 1919, was discharged from the C.E.F. on demobilization.

On discharge, Steele was issued the Class "A" War Service badge numbered 270176. He was also eligible to receive a War Service Gratuity of $420. Mary Steele received a spousal amount of $180. Cheques were issued to them in five instalments between May and September 1919.

The award of Steele's Military Medal was formally published in the London Gazette, Issue No. 31430, dated 3 Jul 1919 and was entered in his service record on 9 Aug 1919.

After two and one-half years overseas, Steele's family was struck by tragedy eight months after his return home. On 13 Dec 1919, The London Advertiser published an obituary notice for Mary Steele:

"Death of Mrs. Steele

"Mrs. Mary Steele died Friday [12 Dec 1919] at St. Joseph's Hospital after a short illness, in her 51st year. She is survived by her husband, Thomas Steele, one son Frank, and one daughter, Mrs. L. Kipp, both of this city.

"The funeral will be held on Monday morning from the family residence, 17 York St., to St. Peter's Cathedral at 9 o'clock. Interment will be made in St. Peter's cemetery."

Frank (Francis Paul) Steele was Mary's son by George Munroe although he had taken Thomas Steele's surname. Frank also served in the C.E.F. during the First World War. He had enlisted with the 33rd Overseas Battalion at the age of 19, service number 400851. Once overseas, he joined the 58th Canadian Infantry Battalion as a reinforcement in September, 1916. Frank achieved the rank of Sergeant while with the 33rd Bn., reverted to Private to go to France, and was briefly an Acting Corporal with the 58th Bn. (reverting once again, at his own request). In October, 1916, he was wounded, suffering a gun shot wound of the left thigh. After recovering from his wound, Frank returned to France to join the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles in November, 1917. With this unit he rose to the rank of Sergeant in July, 1918. Frank was wounded again (shot wound, chest) in September, 1918. He would not return to his unit and would be discharged at London, Ont., on 8 Apr 1919. At the end of the war, Frank Steele was awarded the French Croix de Guerre to accompany the service medals he would receive, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. Frank died on 27 Feb 1956 at Hamilton, Ont.

Thomas's younger brother Henry "Harry" John Steele also served in the C.E.F. Claiming prior service of two years with the 1st Hussars (London, Ont.), he signed an attestation form for the 33rd Overseas battalion on 13 Jan 1915 (#558). No other document in his service record refers to this enlistment. His name next appears in The London Advertiser on 11 Sep 1915 which includes "Henry John Steele" as a new enlistee for the 70th Battalion at London. Again, there is no followup evidence that he remained with this unit. Finally, he enlisted with the 142nd Overseas Battalion on 10 Dec 1915 (#823203). Henry Steele landed in England on 11 Nov 1916 and was taken on the strength of the 14th Canadian Infantry Battalion on 30 Nov 1916. Eleven months later, on 31 Oct 1917, he suffered a G.S.W. (gun shot wound) caused by shrapnel to his right hand. After spending months in hospital while the medical staff combated the severe infection of his wound, it was confirmed that the partial loss of function of his hand made him unfit for further military service. Henry Steele was invalided to Canada in May 1918 and discharged, medically unfit, on 7 Aug 1918. He dies at London, Ont., on 26 Jul 1946.

The surviving daughter mentioned in Mary Steele's obituary notice was Hazel Gertrude. She married Charles Llewellyn Kipp on 11 April 1919, and was the first of Kipp's three wives. Kipp had served in the C.E.F., proceeding overseas with the 4th Draft from the 1st Depot Battalion, Western Ontario Regiment, and serving in England (#2355305). The couple were living in Detroit, Michigan, at the time of the birth of their son in August, 1924. Hazel died in Detroit on 10 Dec 1933.

For his service in the C.E.F., in addition to his Military Medal, Thomas Steele was entitled to receive the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. These were despatched to him at 17 York St., London, Ont., on 5 Sep 1929.

Thomas Steele died at Westminster Hospital, London, Ont., on 16 Apr 1948. The cause of his death was recorded as pulmonary edema due to cardio renal disease and hypertension. Steele was buried in St. Peter's Cemetery, London, Ont. (grave #9, Lot 30, Sect. C).

Pro Patria

Visit a randomly selected page in The O'Leary Collection (or reload for another choice):

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

The O'Leary Collection—Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment

Newest additions:

![]()

![]() SB-12725 Private Henry "Hank" Ard

SB-12725 Private Henry "Hank" Ard ![]()

WIA at Hill 187, Died of Wounds in Japan

![]()

![]() 2355331 Lance Corporal Albert Lorking

2355331 Lance Corporal Albert Lorking

Wounded in action, later a War Amps representative.

![]()

![]() 4334 / 477996 Pte Isaac Hamilton Wilcox

4334 / 477996 Pte Isaac Hamilton Wilcox

Permanent Force, South Africa, and C.E.F.

![]()

![]() 477019 Private Harold Ashcroft

477019 Private Harold Ashcroft

Transferred to the Tunnelers.

![]()

![]() 734231 Private Clark D. Thompson

734231 Private Clark D. Thompson ![]()

The older Thompson brother, killed in action.

![]()

![]() 733849 Private Norman Parker Thompson

733849 Private Norman Parker Thompson

The younger Thompson brother; post-war service in the Special Guard.

![]()

![]()

![]() A305 / 400305 Private Andrew Walker

A305 / 400305 Private Andrew Walker ![]()

"Previously reported Wounded, now Killed in Action."

![]()

![]() 823298 Pte Thomas Patrick Steele, M.M.

823298 Pte Thomas Patrick Steele, M.M. ![]()

… for gallant conduct in the field …

![]()

![]() P13066 Sergeant Harold Thompson

P13066 Sergeant Harold Thompson

Instrumental Soloist for over 20 years of Canadian Army service.

![]()

![]() 9609 / 477728 Private Albert Edward Piper

9609 / 477728 Private Albert Edward Piper

"Arrived from England as a STOWAWAY …"