The Rise, Fall, & Rebirth Of The 'Emma Gees' (Part 1)

by Major K.A. Nette, PPCLI

(First published in the Infantry Journal No 8 - Winter 1979)

Go to Part 2 of The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of 'THE EMMA GEES'

The term "EMMA GEES" was the nickname used for machine gunners during World War I. I thought it an appropriate title for this series of articles as World War I was the Canadian machine gunners' finest hour. They were the first to perfect the machine gun barrage and the first to form machine gun units. They became the recognized authority on machine gun employment and their techniques were eventually adopted by the British, French, Belgians and Italians. Between the wars and during World War II we still maintained dedicated machine gun units. The state of the art remained high until the late 60's when the machine gun became a "hey you" weapon. In five short years we came close to losing expertise that had taken 50 years to develop.

When I was first commissioned in 1963 (not really all that long ago) our battalion machine gunners were considered specialists, the same as the mortarmen, pioneers and anti-tank gunners. On exercises, we normally had a machine gun section attached to the company. Their guns were always well sited and carefully coordinated with the battalion plan. This all changed; however, with the introduction of the APC. Suddenly we became a machine gun battalion. and went through the motions of teaching the troops how to load, unload and fire these weapons but their tactical employment was neglected badly. A few dedicated souls attempted to keep the art alive but their efforts were doomed from the beginning. The machine gun wing at the School of Infantry disappeared and the advanced machine gunner qualification was deleted from the books.

The formation, in 1974, of the Tactics Doctrine Board to study the tactical employment of machine guns was the First of the labour pains accompanying the rebirth. The document they produced is well on its way as an amendment to the official machine gun CFP. it also forms the basis of the tactics instruction given students on the Advanced Machine Gun Course, reintroduced in April 1977.

As Small Arms Platoon Commander at the Infantry School, these past two years, I have been closely involved with everything concerning machine guns. I have preached to students at every level, from the potential platoon 2IC to future company Commanders. There is one group, however, that I have been unable to reach - the regimental officers Currently in command positions in our battalions. I am hoping that through the Infantry Journal T can reach this important group.

I first decided to write this article while a DS on the Infantry Officer Phase Four Course, last summer. During a TEWT, one of the other DS, an officer I respect as a competent professional, criticized a student on the way he had deployed one of his platoon machine guns. The DS was a graduate of both the Company Commander's Course and the CLFCSC at Kingston. The student, however, had recently attended an Advanced Machine Gun Course. The gun in question was sited perfectly and complied with one of the basic principles of machine gun employment. The DS simply didn't know. How many other blissfully ignorant people do we have commanding in the field right now, I asked myself. Thus this series of articles was launched.

This is not a fire and brimstone presentation damning every officer who has ever misused a machine gun. I am not without sin myself; therefore I am not qualified to throw the first stone. Neither is it an outlet for my own theories. It is strictly an elaboration on how Infantry machine guns should be employed according to Official Canadian Forces Doctrine.

It is often said that the secrets of the future can be learned in the lessons of the past. Canada's machine gun heritage is most worthy of study and for that reason, I have devoted the entire first article to it. The article is in two parts: World War I and World War II. The World War I segment is as authentic as a thorough study of official histories can make it. All of the events described actually happened. The Old One, however, is a figment of my imagination. The World War II characters are all real. Lance Corporal Doug Riggs exists and is currently a Major in the Cadet Services of Canada, working out of Oromocto, New Brunswick. To him go my thanks for his patience during those hours when I tried to match his memories up with the official Canadian Army history.

Let us now slide our minds back 60 years and join the Old One and his "Emma Gees" as they prepare to take their place in the front lines.

THE OLD ONE

A low overcast hung over the pock-marked field east of Arras that night in August 1918. All was quiet in the small French farming community just behind the front lines. The men of the machine gun company lounged around, making themselves as comfortable as possible, waiting for the sun's last rays to die. They had moved into the village that morning and now waited for the cover of darkness before relieving their sister company of the 2nd Battalion of the Canadian-Machine Gun Corps. They were a mixed lot. Some were veterans of many battles while others were new to France and had recently graduated from the Canadian Corps Machine run School at Aubin-St Vaast. Some had been Machine Gunners for years, while others had only recently joined the Corps from the various infantry battalions. They were organized into four batteries, each of four two-gun sections. They sat around in their section groups waiting for the signal to move out. Some were still finishing their supper of bully beef and biscuits, but the more experienced ones slept, for it would be a long night.

The young private was too nervous to either eat or sleep. He turned to the lance corporal lying on the straw next to him and said, "What's it really like in the trenches, is it really as bad as they say?"

"Worse at times", the NCO replied, "but don't worry, lad, the Old One was up on a recce last night and he says these holes are pretty dry right now. You may have lucked in for your first tour".

"What is going to happen tonight?", the young soldier continued. "I know the Old One briefed us all this afternoon, but would you believe I can't remember a word of it."

"Don't worry about it, lad," the veteran assured him. "We all went through the first tour jitters. You'll settle down after a few days. (I'll have to keep a close eye on him for those few days, though, he thought to himself.)

"The company will probably start moving out in about 20 minutes. We'll be the last to leave as we don't have as far to go as the other batteries. We'll leave our limbers at the beginning of the communications trench and pack everything forward from there on our backs. There will be a guide from the section were relieving and he'll take us forward to the gun pits. The guns go in first with as much ammo as we can carry. Then we'll make as many more trips as are necessary to get the rest of the area, water, rations, etc up. If we are lucky, the guns we're replacing won't have been in much action lately and will have lots of ammo on the position. If that's the case, we just take it over from them and they replace it from our limbers on their way out. It saves us all a lot of work. We do the same thing with tripods, but for a different reason."

"Yes, I know all about that.", the young soldier interrupted. "By leaving their tripods and aiming stakes in position, we just take over their range cards and don't have to worry about registering targets."

"That's right," the lance corporal answered. "Mere will be lots to do for the first few hours and we probably won't get any sleep tonight, but don't worry. I'll be right beside you to tell you what to do."

"I couldn't sleep anyway," the soldier replied. "Don't those guns ever stop? They've been going all day."

"After a while you get so tired you don't notice them until they do stop. Then, you'll be wise to stay alert because it is sure as hell a signal that something is going to happen. You had better concentrate on keeping your head down anyway for the first few days and don't get too curious about what the German line looks like. They will have all our gun positions pegged and we are prim targets for their snipers. They don't call our Corps the suicide club for nothing."

"I'll remember that. I want to live to see the end of this war."

"Well if that's the way you feel, stay close to the Old One. He has been through it all and is still alive and kicking. Left Canada with the First Division back in '14, he did. Was one of the originals in the Motors."

"Is that why they call him the Old One? He doesn't really look that old, does he?"

"No, he doesn't. I wouldn't say he's much over thirty, but this war has been hard on him. Listen to the way he breathes as he sleeps. That's what poison gas does to you. He also has a bad leg, but he'll never admit it. He's a survivor though. They say he was once buried alive for over five hours back in 1916 and when they finally dug him out, he didn't even go on sick parade. No, he's got a lucky star shining on him and we will both do well to stay close to him."

Their discussion faded with the twilight and soon it was time to move. They could hear men, mules and wagons shuffling around them. "Shouldn't we wake him up?" the young soldier asked the lance corporal.

"Not just yet," he replied. "As I said before, we will be the last to leave, so we've got a little while yet. Let him rest."

It wasn't long, however, until one of the battery runners appeared and said: "get ready, Captain says we'll be moving in about 10 minutes."

The lance corporal carefully nudged his left shoulder and the Old One awoke instantly, his reflexes honed to a fine edge by his years in the trenches. Instinctively, he reached for his gas mask, and reassured by its comforting presence, took quick stock of the situation. He listened to the gunfire and by its tone, knew he wasn't in the front lines. He glanced around and suddenly it all came back. They had been out of the line in rest billets and were now on their way back up. It must be almost time to move, he thought to himself as he slowly got to his feet. His left leg was throbbing painfully. "Everything ready to go?" he said to the corporal. The NCO nodded his answer and seconds later, the word to fall in was passed down the line. Five minutes later, they were on their way.

As they walked along the road, the sound of the guns became louder. Soon, they were among the field batteries, their muzzles flashing on either side with ear-splitting bangs. Every now and then, they could make out the whistle of an incoming enemy shell but none landed close enough to cause concern. There were others on the road, mostly administrative personnel bringing up rations, ammunition and the like. Faceless shapes in the dark, each group going about its own business. Eventually, they arrived at the entrance to the communications trench where the guide was waiting for them. The rest of the battery had disappeared, each section to it-5 own RV. They had arrived at The Front.

The Old One had a brief chat with the guide, then signalled the section to start unloading the limbers. "The guide says they've got lots of ammo on the position," he said, "so we'll just take a few belts up with us. He says the Germans have been lobbing gas shells all day so make sure you can get your masks out in a hurry."

Before long, the section was moving again, this time each man was straining under a heavy load. The young soldier carried the 40 pound vickers gun over his right shoulder and a partial belt of ammunition around his neck. He gazed around awestruck. Me trench was deep, deeper than he thought it would be. Me walls were shored up in places with timbers and sandbags were everywhere. The bottom was lined with duckboards. Every now and then, a rat would run across in front of him. Me whole place smelled of death. They periodically passed other columns moving the other way. Some of the troops carried stretchers while others carried empty sandbags. Soon, they would retrace their steps, but this time the sandbags would be filled with the bread, cheese, bully beef and bacon that were the standard fare of the front line soldier. The trench was like a snake, twisting and turning this way and that. For what seemed an hour (but was really much less), he followed closely behind the lance corporal. Suddenly, the column stopped. Me lance corporal turned and whispered "we've just come to the support line. The guide is clearing us through the sentry. We don't have far to go now. Do you want me to take the gun for a while?"

"No thanks, I've brought it this far and I can make it the rest of the way," the young man replied.

Soon, the column was moving again. Now, they were making their way through occupied trenches. There were troops everywhere; some on the move and some in residence. Every few minutes, a Very light went up, bathing the barbed wire in an eerie blue-green light and there was sporadic machine gun fire up and down the line. The artillery was still firing steadily, but both sides were aiming at targets in depth. For the moment, the front lines were reasonably quiet.

Suddenly, they were there. Two members of the outgoing gun crew were on the position, waiting patiently for relief. The rest were back in the section dug-out getting their kit ready. The lance corporal had a quick chat with his counterpart, then signalled for the private to bring the gun forward. They quickly dismounted the outgoing gun and slapped their own in its place. "They figure they can get all their kit out in one trip if we help them," the lance corporal said to his crew. "I'll stay here and finish the handover. I want the rest of you to go back with these chaps. They'll then help you bring the rest of our kit up. when you get back, I'll have the duty roster ready and some of you can get some rest."

As the small column moved back towards the dugout, the gun commander continued with the handover. First, he checked the bedding of the tripod making sure it hadn't shifted when they changed guns. Then he checked the gun itself, making sure the water jacket was filled to the right level and the condenser can was two-thirds full. He pulled the string to check the night aiming lamp 15 yards out in no man's land and then went over the target list.

Like a shadow, the Old One slipped into the machine gun pit. "Me other gun is about 20 yards over there," he said. "Unless I say otherwise, you will always fire together. I'll be in the trench between the two of you. There is a field phone to battery HG there and another one in the dugout. Any problems with the handover?"

"No, everything seems in order. We could come into action now if we had to," the lance corporal replied.

"Good. I expect the troops will be back before too long, then we can get our normal routine going. How is that replacement making out?"

"Young and scared," came the reply. "He seems keen enough, though. I think it might be a good idea if you had a chat with him. Try and calm him down a little."

"I'll keep my eyes open for the right moment," the Old One said and as silently as he had arrived, he departed.

The right moment came two hours later. The Old One was sitting in the dugout studying a sketch of the position by the light of a solitary candle. The dugout was about 10 feet square and roofed with sagging, smoke blackened timbers. Along two walls were narrow wire netted bunks, occupied by members of the section. There was a brazier for cooking and heating and a crude table in the middle. Not a bad hole, he thought. Suddenly, there was a loud explosion just outside the door and the young replacement flew through the gas curtain, straight into his arms. As they both got to their feet, the younger one started shaking like a leaf. "Calm down," the sergeant said in a soft voice. "that was just a 5.9 shell. Just thank your lucky stars you were on your way in when it hit. You will have closer calls than that before this is over."

Trying desperately to regain control of himself, the young soldier looked at the sergeant and said "I guess you've had lots of close calls. Have you really been here since 1915?" "That I have," the Old One replied. "Sit down over here and I'll tell you all about it." He turned to the signaller, religiously maintaining his vigil by the field phone and said "put some water on for tea, would you." Then he sat down beside the youngster, lit up a Woodbine and began to talk.

BRIGADIER GENERAL RAYMOND BRUTINEL CB, CMG, DSO, Commander Canadian Machine Gun Corps 1914-1919.

In 1905 Raymond Brutinel emigrated from his native France and took up residence in Edmonton, Alberta. He was active in development of the West and by 1914 was a millionaire. Still a captain in the French Reserve Army, he had been following military development and had developed theories on the use of machine guns that were far ahead of his time. When mobilization came in 1914, he formed the Automobile Machine Gun Brigade, and raised the funds for its equipment. As a major, he commanded this Brigade in France. When the Canadian Machine Gun Corps was formed, in 1917, Brutinel was appointed its commander. By then he had gained a reputation throughout the Allied armies for his innovations in the tactical handling of machine guns. Under him the Corps achieved a place half way between the Infantry and the Artillery. Each division had a Machine Gun Commander with similar powers to those of the CRA in respect to artillery. After the war, General Brutinel became military historian in the War Narrative Section of Army Headquarters. In 1920, however, personal f actors forced his return to France, where he remained until his death, at the age of 82, in 1964.

"You see," he began, "both my parents were born in England so when the call for volunteers came out it only seemed right that someone from the family had to go. My older brother's wife had just had twins so we couldn't expect him to leave and Billy was only 14, so that left me. We lived just outside of Ottawa so one morning, I just said a fast goodbye and jumped on a train. At the station, in Ottawa, I saw a sign advertising for recruits for the Automobile Machine Gun Brigade. It said they were looking for people who had done mechanical work and interested persons were to report to a Major Sifton at the Chateau Laurier Hotel. Well, I was a mechanic of sorts and this looked more interesting than just being a straight infanteer, so away I went. I didn't have any trouble finding the Major's suite as there was a line up stretching back to the main lobby. Eventually, I got to the front of the line and the next thing I knew, I was on my way to the field camp at Valcartier over in Quebec.

"There must have been 30,000 of us there. Only 125 of us were with the machine guns, though. We were late getting organized and really didn't do much training before leaving Canada. We were sort of like the "Princess Pats" in a way. Fifteen wealthy businessmen chipped in to raise $150,000 for our kit. General Brutinel was our CO; of course he was just a major then. Our equipment consisted of 20 Colt machine guns and eight armoured cars. The Major picked the guns up from the factory himself using one of the armoured cars. Good thing he took the armoured car, because he was ambushed just outside the plant by a group of German sympathizers. The way I figure it, those must have been the first shots fired at a Canadian during this war.

"We boarded our ships at Quebec City, let's see - I guess that would have been about the 1st of October. What a hive of confusion that was. We were all on the - same ship, but our kit was scattered throughout the fleet. It took weeks to sort it out once we got overseas. The crossing took almost two weeks. We stayed on board for two more days before debarking at Plymouth, then there was a seven hour train ride and a 10 mile march. We moved into tents on Salisbury Plain and started training right away. It wasn't a bad place when we first arrived. That didn't last long though. It rained for 89 out of our first 123 days there. Something about the soil kept the water from draining off and the whole place turned into a swamp. Somehow, we managed to survive, though, and we got in some good training to boot. Mainly infantry stuff at first, but eventually, the Major came up with some machine gun training manuals - I think he wrote them himself - and we got serious about what we saw our role to be in the battles to come. We took those Colt guns apart so many times, it's a wonder we didn't wear them out. We weren't considered machine gunners until we could strip and assemble them blindfolded. The only thing we didn't get to do was fire them. It seems the British authorities were concerned about us chewing up their turf.

"We weren't the only machine gunners around, though. Each of the infantry battalions had four Colt guns as well. We spent a lot of time working with their machine gun sections. I must admit we were a little too cocky at times. We used to drive around in our cars showing off a lot. Each car carried two guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. We figured we could whip the Kaiser's Army all by ourselves and we were rather vocal about it. Boy, did we get our comeuppence when we didn't go to France with the Division.

"I remember the day we paraded for the King. It was during the first week in February. We were originally supposed to fall in like regular infantry, but Major Brutinel wasn't having any of it. He said we were the Motor Machine Gun Brigade and our motors had as much of a place on the parade as we did. Anyway, he formed us up in three lines with the armoured cars out front and the ammo trucks and repair vans in the back. The officers, drivers and number one gunners stood in front of the cars and the rest of us lounged in the back, oblivious to what was going on outside. We were just considering getting a card game going, when we heard a scuffling noise outside the car and the next thing we knew, the King was staring down at us. I don't know who was more surprised, him or us. We all jumped to attention and in doing so almost knocked him over. Fortunately, the King had a good sense of humour and he chuckled about the whole thing. He was real interested in us and our kit and gave us a good looking over. He was standing beside our car waiting for his horse to be brought over when he turned to Lord Kitchener and said 'This is a pretty useful unit.

'I'm afraid not, Your Majesty,' Kitchener answered. 'It would be most difficult to employ, and would throw out of balance the firepower of a division.'

"That night, Major Brutinel gathered us all together and gave us the bad news. General Alderson, the Division Commander, agreed with Lord Kitchener. We would not be going to France.

"We lounged around Salisbury Plain for a few days after the Contingent left, then moved to Kent where we did so-called coast guard duty. The only good thing that happened there was that we finally got to fire our guns. We found some old limestone quarries where we fired for hours, practicing clearing stoppages. And I'll tell you, that old Colt gun sure had its share of them. We kept hearing rumours that we would be getting Vickers guns soon, but when we finally did get to France, in June, the Colts were still with us."

The Old One shifted his position and lit another Woodbine. The signaler took advantage of the lull to pass around mugs of tea. One of the sleeping figures on the wire net bunks had awoken and two other members of the section had entered the dugout and were listening attentively. "What were things like when you finally did get to France," one of them asked.

"Well, the line was pretty quiet then," the Old One continued. "There had been some terrible fighting earlier on that year, but both sides were sort of licking their wounds, you might say, and getting ready for the next go. The Canadians were up north of Armentieres when we joined them. We established and manned a series of strong points all along the Division's front; then, used our cars as mobile anti-aircraft sections. We used to drive up and down the roads, just back of the lines, taking pot shots at enemy reconnaissance planes. We got quite a few of them, too.

We were looking forward to meeting the machine gunners we'd worked with on Salisbury Plain, but we soon quit trying to find them. Almost all of them were dead. Yeh, in those days, we still had a lot to learn from Jerry about machine guns. His Maxims were better than our Colts and he had more of them. His generals seemed to know how to use them more effectively than ours did, as well. One of our officers told us that the Germans had sent a bunch of observers to some war the Russians and Japanese had a while back to see how they used their machine guns. When these guys came back to Germany, they spent eight million marks developing machine gun units.

"The one thing we got into before the Germans did was indirect fire. Everyone is using it now, but in those days, no one had tried it. Brutinel was a Lieutenant Colonel by then and held been playing around for some time with models and trajectory charts. We were set up in a stable near a place called Chateau La Hutte about 1500 yards behind our front lines. One day in late September, the Colonel arrived and gave us a bunch of data he wanted to put on the guns. He said that there was a high ridge about 500 yards behind the German front lines where their Artillery officers used to meet every day. He planned on giving them a surprise the next time they showed up. We didn't have long to wait and boy, did we ever give it to them. We fired four guns at a time and everyone got a chance to try it. It made the Germans so mad, that they brought an eight inch gun up and put 10 rounds into the Chateau, levelling the place. It didn't bother us an as we were in the stables.

"Well, that really started thing rolling. Next thing we knew, we were doing all sorts of experiments. It took a while to catch on though. The infantry didn't care much for us firing over their heads. We had to be awful careful at first because those Colt guns had some funny quirks. One was that the first round always fell short. I remember one day we were practicing our drills when the Colonel brought some senior officers over to watch. One of them seemed rather sceptical about the whole thing and brought up the problem of the first round. 'Oh we've solved that,' the Colonel said. 'We always remove the first round from the belt.' We all broke out laughing, but I don't think our visitors were amused.

"We weren't involved in any major operations during the winter of 1915-1916. The infantry were very busy with night patrols and trench raids, though, and we supported them a lot. Our biggest problem was just surviving in the trenches.

"Things started to happen once spring arrived. The Canadian Contingent had become a Corps by then. The Borden Battery had arrived in France and joined our Brigade and each of the infantry brigades now had a machine gun company. I'd been promoted to lance corporal and was commanding a gun. We were supporting 2nd Division, who had moved down to the Ypres salient in February. In late March, the British launched a major attack near St Eloi. For months, their engineers had been digging tunnels under the German lines. They crammed them with explosives, then just before the attack, they blew the whole German front line sky high. I didn't see it actually happen, but I understand it was really something. The problem was that the explosions destroyed all drainage and obliterated all landmarks. The Front, in that area, suddenly consisted of seven huge craters half filled with water with seas of mud between them. The British were supposed to stabilize the new line; then, we would take over from them. Well, the line was anything but stable when we arrived. Our cars were no good to us there, so we manhandled the guns and ammo forward through the mud. Things were completely confused and nobody seemed to know what was going on. Enemy f ire was coming from three directions and we took a lot of casualties. I lost my gun and one of my men on the way in. We were making our way along the edge of one of the craters, when the fellow carrying the gun slipped and slid down into the noddy water. He just kept on going and never came up.

"There was as much fire behind us as in front so we just kept on moving. We'd completely lost contact with the rest of the battery and I was wondering what to do when we ran into a group from the 31st Battalion. They had a Colt gun with them, but didn't know what to do with it. The crew had taken a direct hit from a shell and the gun was damaged. We were able to get it working again, using spare parts from our kit, so we were back in business. Just in time too, as a German attack came in right about then. There was another gun over on the other side of the crater, I haven't a clue who they were, and we caught the Jerries in a cross fire. We held them up for a while, but there were just too many of them. Eventually, we had to fall back. The other gun didn't make it.

"We stayed with the 31st Battalion for the rest of the battle. Sometimes, we were attacking, sometimes defending. It went on for days and eventually I stopped caring. I lost my whole crew there and had to quickly train a couple of infanteers to work the gun with me. We were supporting an attack one morning when there was a blinding flash right in front of us.

AN ARMOURED CAR OF THE 1ST CANADIAN MOTOR MACHINE GUN BRIGADE (THE "MOTORS") - Each car originally carried two Colt guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. In 1916 the Colt guns were replaced with the more efficient Vickers guns.

"I guess I was one of the lucky ones that they were able to get out. Most of the other wounded just died where they lay in the mud. I was unconscious for hours, but finally came to on my way back to the field hospital. My left leg was hurt pretty bad. No bones were broken, but I had a bad rip in my thigh. On top of it all, I was just plain worn out. All told, it was enough to keep me out of the line for almost three months.

"I joined the Brigade again in late July. They were still in Flanders, but things were pretty quiet. The organization had changed a great deal during my absence. We now had five batteries, the Eaton and Yukon batteries having arrived from England. The Colt guns were gone, finally being replaced with Vickers guns. The Colts had also been withdrawn from the infantry battalions, but they got Lewis guns in exchange. Probably the most significant change for them was the withdrawal of that aid-to-the-enemy the Ross rifle. They were now all carrying shiny new British Lee Enfields.

"I went back to my old battery, but couldn't really settle in. There were very few people I knew. The casualties at the St Eloi Craters had been devastating and most of those who did survive were killed either at Sanctuary Wood or Mount Sorrel. All the Officers were new and I didn't really hit it of f with any of them. The 4th Division was just arriving in France and the word came round that they were looking for experienced machine gun NCOs for their brigade machine gun companies. I figured the time had come to say goodbye to the Motors, so I put my name in and off I went. It got me a promotion to full Corporal to boot.

"I was assigned to the llth Infantry Brigade Machine Gun Company where I took over a Vickers gun. We entered the line in late August as part of a mixed up organization called "Franks' Force". There were Belgians, Australians and British units all under command of some British General called Franks. The other three Canadian divisions headed off south to the Somme. God, am I ever glad we missed the first part of that show. I guess it was a real blood bath, especially for machine gunners.

"We spent some time at the St Omer training area in September, then headed off to join the rest of the Canadian Corps on the Somme. We got there just as what was left of them was being pulled out of the line. I think it was the 10th or 11th of October when we relieved the 3rd Division. We came under command of some British outfit, I think it was the 2nd Corps, and started getting ready for an attack on a place called Ancre. We had a couple of days of decent weather then it started raining and it looked like it was never going to stop. The trenches became knee deep in mud and the dugouts all flooded. We had to burrow under the parapets like ground hogs to get out of the rain. We stopped doing this after a while, though, because the shelling caused cave ins and we were loosing too many men. I was trapped in one myself for a while.

"The offensive finally got off about two weeks later. I was supporting the 102nd battalion at the time and their objective was a section of the German line known as Regina Trench. All of the other Canadian divisions had had a go at this position and been beaten back so we were expecting the worst. As it happened things weren't too bad. Our Artillery did a good job of cutting the German wire and then provided a walking barrage ahead of our troops. We manned strong points and supported them with overhead fire while the battalion machine gunners went forward with their Lewis guns. The Battalion had their objective secured within 15 minutes of zero hour, then we moved forward to help them repel the inevitable counter attacks. The Germans tried to take the trench back several times but each time out artillery got the best of them.

"We held that piece of trench for several days. 10 Brigade on our right had a few problems and it was several days before they were secure on a line even with us. Once they had consolidated, we all got ready for another big push. We were all rather anxious to get moving. The rain hadn't let up much and the constant bombardment of the area, first by us then by the Germans, had reduced the trench line to a mere depression in the chalky soil. There was garbage everywhere and bloated bodies all over the place; too many of them wearing the blue patch of our 2nd Division. The attack was postponed several times because of the weather, but we finally got going during the second week in November. We were still supporting the 102nd battalion and carried on as we had before. The Germans concentrated their artillery on our gun positions, though, and our casualties were heavy. I took a piece of shrapnel in the shoulder and was evacuated later on that day.

"The medics had me patched up in no time and I rejoined the company about a week later. The offensive was over by this time and our Brigade had advanced almost half a mile. The weather had turned cold and there was snow and sleet mixed with the rain. Just surviving was a major effort. We were always wet and most of us suffered from trench foot. Every time the temperature dropped below freezing, our clothes froze. Our greatcoats knocked against our ankles and made walking extremely painful, unless we had thought to pin them up before the thermometer dropped. The 72nd and 85th Battalions had it particularly bad. They are highland battalions and when their kilts froze, it made a bloody mess of their legs. Because of the conditions, they didn't leave us in the front lines very long but kept rotating us around. The nearest billets were eight miles back, though, so even being relieved was exhausting work. The Division was finally pulled out of the line near the end of November and we joined the rest of the Canadian Corps not far from where we are right now. I tell you, never in my life have I been so glad to leave a place."

The Old One lit another cigarette and was about to continue when the gas curtain was thrown back and a sentry stuck his head in and said "stand-to". One by one the men heaved themselves to their feet, picked up their rifles and made their way out the entrance to their predetermined positions. Signallers, runners and gunners alike, they all stood alert during that critical hour straddling first light.

Stand-to over, the hum drum routine of a day in the trenches began. First, there were the compulsory ablutions, then, breakfast followed by a general clean LIP. The shelling was light on both sides and only occasionally did it interfere with the work parties repairing damage caused by previous barrages. The young private sat behind the Vickers taking his turn "on the gun". The day was warm and the air was stilI. Suddenly, he felt very, very tired. "I'll close my eyes for just a moment," he thought.

The next thing we knew he was being rudely shaken back to consciousness by the lance corporal. "Don't let the Old One catch you catnapping like that", the NCO admonished. "He'll tolerate a lot of things but sleeping on sentry duty isn't one of them."

"I wasn't really sleeping", the soldier answered. "I was just resting my eyes a bit."

"Well don't let him catch you at it. He'll have you up on charge for sure," the lance corporal warned, speaking over his shoulder as he headed for the dugout.

The young soldier, now very alert, continued his vigil. Soon, however, the old weariness returned. He started looking for things to occupy his mind. He counted all of the sandbags around the position, then gazed out at the barbed wire, counting the pickets. Past the barbed wire was the German line, devoid of all visible signs of life. "I wonder what it's like over there," he said to himself, craning his neck for a better look. Without realizing what he was doing he slowly raised himself higher, exposing his head and shoulders over the edge of the parapet. Everything seemed to happen at once. The Old One appeared out of nowhere, grabbed him by his web belt and hauled him down just as the sniper's bullet cracked the air where his head had been.

As he slowly got to his feet and brushed the dirt from his battledress, the realization of how close he had come to death overcame him and he began to shake. "'Th-th-thanks," he said to the Old One.

"Your lucky I happened along," the NCO replied. "You wouldn't have been the first gunner I've lost to a sniper's bullet. You always have to assume that there is a sniper watching your gun pit just waiting for you to stick your head up. I remember one day last year, just after we took Vimy Ridge, when I lost two men in one day. We were supporting the 54th battalion that - lay on the edge of the Bois De La Folie just south of Givenchy. The Jerries were on the run by then but they left a pretty effective rear guard behind. Yep, you've got to keep your head down whenever you're near a Vickers gun in the front line; no matter how quiet things are."

"They told us all about Vimy Ridge during our training at Aubin-St. Vaast. I guess that was some show", the young soldier replied, rapidly regaining his self control.

"I don't want to distract you while you're on sentry," the old One replied, "but remind me after stand-to tonight and I'll tell you all about it."

That evening, after stand-to, the old One made good his promise. The scene in the dugout was similar to that of the night before. The signaller sat watching his telephone, next to that necessity of trench life, the "Tommy Cooker" and its billy can of water. This time there were no shapes stretched out on the hunks. The entire section, except those on duty, were awake and patiently waiting. The Old One didn't often talk about his experiences and they didn't want to miss a word of it.

The Old One took a gulp from his mug of tea then began. "Let's see now, Vimy Ridge would have been a year ago last April. It seems a lot longer; so much has happened since. I was a sergeant by then and still with the 11th Brigade Machine Gun Company. The actual battle wasn't really that much compared to some of the others we've had. `The thing that impressed me the most was the preparation for it. we'd moved into positions just east of the ridge right after they pulled us out of the Somme, near the end of November 1916. The rest of the Corps had been there for about a month and a half and were well settled in. Our company spent a lot of tire in the rear areas training. Brutinel was a full Colonel by then and he sure had the Corp Commander's ear. He had a free hand with the machine gun companies and he was always dropping in to see us, wanting us to try new techniques, especially involving overhead fire. We did a lot of harassing shoots mostly at night working off maps. We worked a lot with the other companies and sometimes with the Motors. I guess we were already starting to act like a separate Corps with Brutinel as the Commander, even though it wasn't official yet. Actually it led to a lot of hard feelings. We were all on the official strengths of different infantry units. They were only too happy to have us and our guns supporting them when the going got rough but they regularly forgot about us when making up their promotion lists. You young fellows who came directly into the Corps don't realize how good you've got it.

"We didn't spend all our time training though. There were quite a few raids and patrols and we supported most of them in one way or another. There was one big raid in early March that involved the whole division. What a disaster that was. For five days in a row the infantry got ready to go over the top just to have it cancelled at the last moment. On the day that it actually went it was, in fact, cancelled but the word only got to the 10th Brigade and most of the Artillery. 11 and 12 Brigade went over the top with very little artillery support and got cut to pieces by the German Maxims. The wind shifted and blew our own chlorine gas back on us so we couldn't support them the way we would have liked to. I don't know how true it is, but the rumour was we had almost 700 casualties that morning.

"As we got closer to the attack on the Ridge itself things got very hectic behind the lines. There were railways 25 feet underground leading up to the front lines, pipelines and reservoirs for water and ammo dumps with tens of thousands of tons of ammo in them. We stepped up our harassing fire programs and were actually part of the preparatory bombardment. This started three weeks before the actual assault, I think. I worked closely with the Artillery batteries. They would fire all day and we would fire all night. We engaged the same targets at night that they did during the day. That way we were able to keep the Jerries from repairing the damage the guns had done. We must have fired millions of rounds that way.

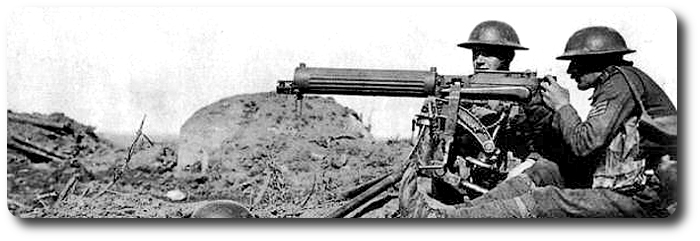

"The actual attack went in at 0530 hours on 9 April. Conditions were perfect from our point of view. The temperature had dropped during the night and there was a stiff breeze blowing snow and sleet right into the German's faces. The artillery was so loud we couldn't hear each other talk. There were 150 Vickers guns firing continuously throughout the whole thing. We laid down a wall of bullets 400 yards in front of the infantry and kept it moving on a timed programme.

"I thought there were over 300 guns at Vimy Ridge," one of the soldiers interrupted.

"There were," the Old One replied, "358 to be exact, including the four companies from the British 5th Division that were attached to us. They weren't all involved in the barrage though. Some went right in with the infantry. A Sergeant I worked with at Aubin-St Vaast was commanding a section of guns with the 8th Company supporting the lst Canadian Mounted Rifles. He got to the Arras- Lens road before they did. Claimed he killed over 100 Germans while the CMR were still getting into position. One gun caught an enemy battalion headquarters trying to withdraw and really gave them what for.

"10th Brigade had a little trouble with the Pimple, a piece of high ground at the north end of the ridge, but by 12 April the whole thing was ours. That battle was the birthplace of our corps. We were the real heroes as far as the infantry were concerned. They said that the crack of our bullets going over their heads was the most comforting sound on the battlefield.

"We took a lot of German prisoners and they had a few comments of their own about us. Some of them spoke English and they told us that they had orders not to take any Canadian Machine Gunners prisoner. That was how bitter they were against us. They said that during the last three nights before the attack it had been next to impossible for them to bring up supplies or evacuate their wounded and during the attack it was impossible for them to man their parapets as long as we were firing.

"It was right after Vimy Ridge that we got the word that authority had been received for the formation of a separate Machine Gun Corps. This didn't really change anything down at our level but it was good for our morale. Brutinel became a brigadier-general and was the official Machine Gun Corps Commander but we didn't form the companies into battalions for almost a year.

"I left the front for a while in 1917 and worked as an instructor with the Machine Gun Wing of the Canadian Corps School. Consequently I missed out on the Scarpe battles and the Passchendaele show. I spent the whole winter at the School then moved to the Corps Reinforcement camp when they set up the Machine Gun Wing there. It was an administrative job. I guess they figured I'd done my share of fighting. I suppose I could still be there now if I'd wanted to but frankly I got bored. It was last March when I finally got back into action. The Germans had broken through between the British Third and Fifth Armies and the Motors were withdrawn from the Vimy positions and thrown in to plug the hole. Brutinel must have been proud because that was the sort of employment he had envisaged for them from the start. At the time, we didn't know anything about the breakthrough but we could tell something was up by the number of reinforcements they were asking for. Then one day General Brutinel came through. With him were a bunch of British Horse Guards who had been removed f rom in front of Buckingham Palace, given a crash course on machine gunning at the School and were on their way to join the Motors. Well I thought to myself, they must really be scraping the bottom of the barrel. I figured the Corps needed me so I packed my kitbag, added my name to the list and climbed aboard the train taking the Horse Guards forward. suppose officially I was AWOL but in all the confusion no one noticed.

"We headed south to Amiens then east to the front. The front didn't really exist between the Scarpe and the Aise River. The Germans had advanced 20 to 30 miles in some areas and nobody seemed to know exactly what was going on. We arrived at Brigade Headquarters, in a barn just east of Amiens, where we were met by Lieutenant Colonel "Tiny" Walker, the CO. He gave us a quick briefing on the Brigade organization and then turned us over to the Sergeant Major who broke us into small groups. The Brigade had changed little since I left it in 1916. It still consisted of five batteries. Each battery had two sections of two cars. The sections were commanded by lieutenants and the batteries by captains. Altogether we had 20 cars. Eight were the same as we'd had before while 12 were a new lighter version. Each car carried two guns and 14 men. The Brigade also had a section of motor cyclists who acted as scouts, dispatch riders and signallers.

"We moved forward that night and my group was assigned to B Battery. We were into the fray right away. took over command of a car and hardly had a chance to talk to the crew before we were on our way. The battery had lost a car earlier in the battle when an ammo dump blew up right beside it, so there were only three of us. The other two formed a section under a lieutenant, I forget his name, and I worked by myself. Our cars would do 25 miles an hour and we needed every bit of it. We were all over the Fifth Army front helping out wherever we could. Our orders were specific: to get in touch with the enemy, kill as many as possible and delay his advance. Sometimes we worked together with one or two of the other batteries but more often than not we worked as sections or individual cars. Often we fought dismounted.

"Supplies were a problem because Colonel Walker never knew exactly where we were and we couldn't always get back to him. Often we just helped ourselves to whatever we could find. I remember one day we were moving back for a quick rest after a bit of action. I had lost a gun in an artillery barrage and one of the other cars had one they couldn't get to work. We were also very low on ammunition. Suddenly we came upon a British Ordnance Depot in the process of packing up to move. The Captain stopped his car and taking five of us with him, walked into the building. He walked up to the British major who seemed to be running things and said, "I need six Vickers guns and 20,000 rounds of ammunition."

The Vickers Gun first issued to Canadian machine gunners during the summer of 1916. Prior to this, machine gun sections were equipped with air cooled, gas operated guns built by Colt based on a Browning design.

The Major looked at us and said, 'Who are you and where's your authority.'

'Haven't any', the Captain replied, 'We're fighting a rear guard action and the enemy is pressing.'

'Can't issue guns or ammunition without proper authority from Corps Headquarters,' the Major countered.

The Captain looked at me, drew his revolver and said, 'This is my authority, go and take what we need.'

'You can't do that,' the Major stammered, 'I'll place you under arrest.'

'Not if you're dead, you won't, The Captain replied, 'now get out of our way.'

"That settled the issue once and for all and the ordnance men helped us load the stuff onto our cars.

"During the second week in April we were ordered to withdraw and rejoin the Canadian Corps. The Brigade had been in action for 19 days without a break. General Brutinel spoke to us and told us what a great job we had done. The cost had been high, however; 75% casualties.

"We went into reserve while we reorganized and rebuilt the Brigade. Then one morning, I was called to the CO's office. The manner in which I had left the reinforcement unit had finally caught up with me. Colonel Walker was pretty good about the whole thing. He said that the CO of the Reinforcement Camp wanted me sent back to face charges but he would write him a letter and try and cloud the issue. He thought it would be a good idea if I left the Motors though. It would make it harder for them to track me down if they decided to push the issue. He said that General Currie had just authorized the formation of a third company in each of the divisional Machine Gun battalions and they were recruiting people from the infantry battalions. He knew the CO of the 2nd Battalion and he would arrange for me to join them. That's how I ended up here."

For a long moment no one spoke. The dugout was stuffy and the lone candle was almost burnt out. The shelling outside had all but stopped. Suddenly the silence was broken by the buzz of the field telephone. The signaller answered it, spoke a few words then looked at the Old One and said, "stand-to, Sergeant. Something happening in front of the 26th Battalion."

Everyone moved at once, scrambling to get to their positions, none of them wanting to be caught in the dugout during a raid. Suddenly the shells started falling thick and fast. The young soldier quickly made his way to the machine gun position. He entered the pit and froze, aghast at the scene in front of him. The shell must have landed right on the parapet. The lance corporal's inert form was sprawled across the ammunition boxes with the headless form of the other gunner crumpled at his feet. For several minutes he stood there. The Old One was shouting commands from his command position and the other gun was firing steadily. Artillery shells were raining down all along the trench line but he was oblivious to it all.

Suddenly the Old One appeared. He grabbed the soldier by the left shoulder, spun him around and slapped him hard, snapping him out of his trance. "26th Battalion's in trouble," he shouted. "They need all the fire we can give them on target number four. Where's your range card?"

While the private searched around the rubble for the piece of paper, the sergeant pulled the lance corporal's body off the ammo boxes and checked the bedding of the tripod. Satisfied that it was still solid, he looked up and seeing the piece of paper in the soldier's hand shouted, "what's the data for number four?"

By this time Very lights were going up all along the line. Under the pale green light the soldier could just make out the figures. "23 up and 10 right," he shouted, now in full control of himself.

"Set the clynometer", the Old One chanted as he opened the back cover and then reached forward to set the bar foresight. He swung the gun onto the aiming stake as the private slipped the clynometer into its slot. He slowly turned the elevating handwheel while the private gazed at the bubble on the level.

"On", the private shouted and lifted the clynometer clear. The Old One snapped the back cover down and said:

"You fire, I'll load."

The soldier jumped behind the gun and grabbed the traversing handles with both hands. Simultaneously he lifted up on the safety catch with the second finger on each hand and pressed the thumb piece with both thumbs. The gun reacted instantly with a long burst.

The battle didn't last long. It wasn't an attack, just a raid and the German hordes were gone as suddenly as they had appeared. The Old One was feeding the fifth belt into the gun when the runner appeared relaying the order to cease fire. It was a warm night and the small of cordite hung heavy in the air. The young soldier wiped the sweat from his brow and suddenly felt drained of all strength.

"Well you've survived your first battle", the Old One said to him, "it wasn't that bad now was it." "Take over here would you," he said to the runner. "And see if you can do something with these bodies. I'll send a couple of the lads up to help you in a minute. Come on back to the dugout with me," he said, his attention turning to the young soldier behind the gun, "I think we've both earned a tot of rum."

ONE MORNING ON THE WINTER LINE

The scene now shifts 800 miles south and advances 26 years to early February, 1944. The Storch reconnaissance plane banked hard to the right and lined up with the snow covered peaks of the Maiella Mountains. Behind it, the newly risen sun peaked over the shimmering blue waters of the Adriatic and began melting the frost from the few remaining window panes in the port town of Ortona. The pilot gazed right and left, looking for the tell-tale signs that would indicate major movement of troops or reinforcement of the forward Canadian units during the night. He carefully scanned the broken trench line to his left and saw nothing unusual. Ever vigilant for the marauding squadrons of Kittyhawk fighters of the Desert Air Force (more than one recce pilot had let his guard down for a moment and failed to return from a mission), he craned his head over his right shoulder and caught a glimpse of the trenches of the 1st Parachute Division. "Good troops, those" he thought. "Loyal to the Fuhrer and the Fatherland." Before him loomed the town of Villa Grande. He kept well to the north of it and swung into a southwest heading and followed along the "Winter Line." north of the Orsogna-Ortona road. Before long, he passed low over the 334th Infantry Divisions's forward units, manning Fontegrande Ridge. Two miles ahead was Orsogna, the western limit of his patrol. He swung in low for a close look at the swastika flag flying over the town hall and then headed for home. It was time for breakfast.

As the plane banked to the right, the sun shone on the underwing markings leaving no doubt as to its nationality. The two machine gunners gazed over the lip of their trench and the taller one said see, I told you it was a kraut. I can always tell by the sound of the engine."

He's just a recce job," the other replied. "It's those Focke-Wulfs I don't like. With these clear skies, I expect every plane in Italy will be up today. I don't know which I prefer, that or the rain. When they told us that we were going to Italy, I visualized sunny beaches and the like. Hell, this place is as bad as Flanders must have been during the first show."

MEN OF THE ROYAL MONTREAL REGIMENT (MG) TRAINING AT LARKHILL, ENGLAND, JULY 1941 - During World War II a Machine Gun Battalion formed part of each infantry division while each armoured division had an independent machine gun company.

As they talked, the two men worked away reassembling their Vickers gun. It had become a routine with them since they had first entered the line. Every morning, immediately following stand-to, they stripped it down completely and gave it a thorough cleaning. As they slapped the last pieces together, the slowly rising sun began to make itself felt and their spirits rose considerably. With an ease brought on by continuous practice, the tall one reefed back on the crank handle while the other fed the belt through the feed block. Number 3 gun was back in action. "Slip over to number 4 and let them know we're back in action, would you, so they can start their morning clean up," the tall one said. "Then you might as well go back to the bunker and get cleaned up and fed. Doug should have the tea made by now. I'll take the first shift."

As his mate slipped out the back of the trench and over to the other gun in the section, the gunner carefully gathered up his tools and, after wiping them off carefully, returned them to the tool box. He checked to make sure the gun was firmly locked on its SOS task, then spread an empty sandbag on one of the more solid looking lumps of mud in the bottom of the trench and sat down to light a cigarette. He savoured the warmth from the match for as long as possible and then cupped his numb hands over the glowing end of the cigarette. He drew long and slow and felt the comforting heat against his palms. Eventually, he pulled the collar of his greatcoat up over his ears and once again stuck his head over the edge of the trench and gazed out over the Italian landscape. His eyes followed the line of German trenches 600 yards away and dwelt momentarily on the burnt out hulk of a Panzer IV, a reminder of a much more violent day. To his left front, in the far distance, stood the Maielle Mountains, their snow capped peaks rising up in splendour. Off to his right stood the town of Orsogna, seemingly deserted except for the German flag fluttering in the breeze. It was the same breeze that cut through his greatcoat like a thousand needles. Shivers ran up and down his spine. His gaze returned to the gun sitting on its tripod like some brass idol awaiting tribute. "Old Hiram Maxim and Albert Vickers sure knew what they were doing when they put you together," he said to himself. "You may be heavy and awkward to move around with, but you sure are dependable in a tight spot. Heck, come to think of it you're not that much of a pain to move around anymore, now we've got the universal carriers." He thought back to his machine gun training in England and the stories the WWI gunners used to tell. He remembered that Veteran from the British 100th Brigade Machine Gun company, who claimed to have been part of the very first machine gun barrage on August 23-24, 1916. He claimed they had fired continuously for over 12 hours and that the 10 guns fired just 250 rounds short of a million. Every spare Train in the Company as well as two companies of Infantry, had been employed full time carrying ammo and water for the guns. "That must have been something to see," he said aloud and gave the Vickers an affectionate pat on the barrel casing.

Suddenly, the gunner was jarred from his daydream by the arrival of his partner, now clean shaven and well fed. "I'll take over now," he said. "Go on back to the bunker for a while."

50 yards to the rear Lance Corporal Doug Riggs sat on a wooden bench with his hands around a tin mug of hot tea and gazed at the candle on the crude table in front of him. Beside him, in the bunker, the section commander finished the last of his breakfast and said "It looks like the weather might be decent today, Doug, so I think we should do a little work on the communication trench. That rain has really made a mess of things, hasn't it."

"It sure has," the young gun commander replied." "I think we should muck this place out a bit too. If we don't keep it clean, we will end up with rats as bed partners for sure. It's bad enough having to put up with you guys." A chuckle vibrated around the room.

"If that's the way you feel," the battle dressed figure across from him said, "you can always sleep in the carrier."

"No thanks," he replied, "besides somebody's got to take care of the rest of you."

The conversation was interrupted by the arrival of the gunner from number 3 gun followed closely by Sgt Lovette, the platoon sergeant. "Morning, Algie", the section commander said; "Just in time for tea. Sit down and have a cup."

"O.K." came the reply, "but I can't stay long. The platoon commander has gone off on OP and I have to stay close to platoon HG. I just dropped by to warn you to stay close to your radio and make sure you've got lots of ammunition handy. We have been given an alternate task of harassing Jerrie's rear areas. Mr. Neil's going to pick some likely targets and we will be registering them this morning. The two sections are too far apart for me to control so the data will cone direct to you from the OP."

"No problem, answered the section commander, "we'll be ready. You had better send a couple of men back to the carriers, Doug, to bring up a couple more cases of ammo, just to be on the safe side."

Two hours later, Riggs was leaning against the side of the trench taking his turn "on the gun." Back in the communication trench his number two and number three were working away filling and arranging sandbags. His driver was helping the guys from number four gun clean out the bunker. Through his binoculars, he carefully studied the German line. No sign of movement anywhere; but then there seldom was during the day. Most of the action took place at night. The German artillery had lobbed a few rounds over them, aimed at their rear areas, about an hour earlier and one had dropped short wounding a couple of the Cape Breton Highlanders, but other than that it had been quiet. He put down the field glasses and leaned back, content for the moment to relax and enjoy the sun.

The Vickers gun as used by Canadian machine gunners during WW II. The only difference from the WW I version was the addition of a dial sight. This weapon remained in service until the 1950s when it was replaced by the .30 cal Browning 1919A4. It is still in service in many of the world's armies and has recently been introduced by the Australian Army.

Two miles to the east, Lt Fred Neil cocked his helmet to the right in an effort to keep that same sun out of his eyes. The sun was shining right into the OP. The camouflage net fluttered in the breeze, throwing eerie shadows across his shoulders where the green and gold flash of the Princess Louise Fusiliers was perched above the maroon patch of the 5th Armoured Division. Below him stretched a wide panorama of olive groves, orange trees and scattered farm buildings. The area was devoid of life; a no-man's land. He carefully lifted his binoculars, his fingers shielding the lenses from the sun's rays, and studied the area north of Orsogna. "Well, I'll be - -," he muttered half to himself. He turned to his signaller and handed him the binoculars saying, "have a look at this. The Jerries are sure getting cocky these days. In broad light, yet." Moving southward along the road, was a column of infantry.

"I make out about 30 of them, sir," the signaller said, "and-wait a minute yeh, they've got five, no six rules with them. They look heavily loaded too."

"Right" says the officer, carefully studying his map. "I figure they should be well within range in about 10 minutes. Have the platoon stand to while I work out the data."

Back on the position, the section commander was trying to figure out a way to drain off the three inches of muddy water in the bottom of the communications trench, when the signaller stuck his head out of the bunker and shouted "fire order coming through, Sarg."

"Take post," the sergeant yelled and dove into the bunker scooping up his notebook from the table on his way to the radio. He flipped to a fresh page and jotted down the first letters of the words in the buzz phrase - LAZY ELEPHANTS LAY DOWN TOGETHER AND SLOWLY ROLL OVER.

Fifty yards forward, Doug Riggs reefed back on the crank handle to fully load the gun, then swung it off the SOS and onto the zero line. Out of nowhere, the other two Fusiliers appeared and took up their regular positions by the gun. Suddenly, the Sergeant yelled "RIGHT 200 - ELEVATION 2800 - LAY."

As the number two repeated the command, Riggs carefully set the data on the dial sight. He spun the elevating handwheel, tapped the traversing handles and as the sight lined up with the aiming stake shouted "ON"

The number four gun commander echoed Riggs' "ON" and the sergeant continued. "SEARCHING FIRE WIND RIGHT 15 MINUTES RAPID WAIT MY COMMAND." Again the number twos repeated the command, then all was quiet.

Suddenly, there was a burst of fire off to their right as numbers one and two guns started firing, 300 yards to the east. Riggs watched their tracers arcing skywards and disappearing over the town. "Stand by, guys", he muttered. "Mat's one section firing, we'll be next."

The words were barely out of his mouth when the sergeant yelled "FIRE". Riggs pressed the thumb piece with both thumbs activating the lock mechanism causing the firing pin to strike the primer of the mark 8Z cartridge. The 40 grains of nitro-cellulose powder flared and sent the 175 grain bullet on its way, clearing the nuzzle at 2,550 feet per second. It quickly reached its culminating point 160 feet above the town, then began its steep descent adding to the "hail of lead" raining death and destruction on the German column. Itfinished its journey, abruptly, in the thigh of a young German soldier cringing in terror, in the ditch.

The young German leapt up and hobbled back along the ditch looking for cover he knew he would not find. Around him was total confusion. There was no sound of firing, only the hollow splat of bullets hitting the muddy road and ditch. He heard the braying of wounded mules and the screams of wounded men. He tripped over a dead comrade and struggled to his feet, now in a complete state of panic. Suddenly, he lurched forward, face down in the mud and moved no more. The war was over for him.

In the OP, Lt Neil smiled and turned to his signaller. "Tell them to cease fire", he said, "anyone still alive down there deserves a break."

Back at the gun position, Riggs returned the gun to the half load and relaid it on the SOS target. "I wonder what that was all about", his number two asked.

"Don't ask me", Riggs replied, "no one ever tells me anything around here. Why don't you go back to the bunker and put the tea on."

EPILOGUE

The Old One survived World war I and went on to serve in the Veteran's Guard during World War II. He died, as all old soldiers eventually must, confident in his mind that the Canadian machine gunner was one of the best in the world. Lance Corporal Riggs also survived his war. He lived to mourn the passing of the era of the Vickers gun and the Machine Gun Platoon. He watched the number of guns, in each battalion, grow while the number of people who could use them shrunk. He saw GPMGs used where a C2 could have done a better job and HMGs left in zulu harbours because the company couldn't afford the riflemen to man them. He started his own crusade to reintroduce machine gun expertise. In 1974 he published an article in this Journal titled "Whatever Happened to Machine Guns?". Shortly afterwards he was invited to join the Tactics Doctrine Board.

The doctrine produced by this board was a combination of the lessons of the past adapted to the needs of the future. In their deliberations they paid particular attention to the fact that:

- the number of guns in each battalion has increased considerably;

- the anti-armour role of the HMG has taken on a new importance;

- machine guns are no longer manned by a few specialists; and

- the command and control organization provided by the Machine Gun Platoon has disappeared.

The findings of this board have formed the basis of the tactical doctrine taught at the School. In the next edition of "the Infantry Journal" I will elaborate on an discuss them. Until then I suggest you have a good look around your unit and identify your advanced machine gunners. We have trained 44 of them so far and if you are lucky you might have one in your unit. Next time you are wondering what to do with your guns, ask one of them. We've put a lot of effort into their education and figure we've done a pretty good job of it.

Go to Part 2 of The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of 'THE EMMA GEES'

For more Machine Gun information, try:

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map