Load Carrying Ability (1990)

Through Physical Fitness Training

Michael S. Bahrke, Lieutenant Colonel John S. O'Connor

Infantry, Vol. 80, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1990

This is the second article in the authors' planned series of three. The first article, "The Soldier's Load: Planning Smart," appeared in the January-February 1990 issue of INFANTRY. It offers guidance on the various factors a commander must consider when planning the operational loads his soldiers will carry. This second article details a physical training program designed to improve our soldiers' ability to carry loads on road marches. The third will provide information gained from a study of the factors that are most important in determining road marching performance.

It is readily apparent that light infantry soldiers today are being required to carry heavier loads than ever before. Data collected from soldiers in the field at the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, for example, indicate that individual loads are averaging 88 pounds. In fact, it is not uncommon for some of these soldiers to carry more than 140 pounds.

When such loads are expressed as a percentage of the average infantryman's body weight (165 pounds), the typical soldier at the JRTC may be carrying between 53 and 85 percent (or even more) of his body weight. Some units report that their soldiers are carrying an average of 99 pounds or 60 percent of body weight, with grenadiers carrying loads averaging as much as 123 pounds (75 percent of body weight) and assistant Dragon gunners 167 pounds (more than 100 percent of body weight).

In many ways, these findings are in direct contrast to planning guidance from the Infantry School, which recommends 72 pounds for approach marches and 48 pounds for combat actions as the maximum loads soldiers should carry. In addition, recent research suggests that loads of 30 to 45 percent of body weight (49.5 to 74.3 pounds) are the most desirable of sustained noncontact movements, with 20 to 30 percent of body weight (33 to 49.5 pounds) being the most realistic for combat missions. (We recommended in the first article in this series that unit loads be distributed among the soldiers in relation to body weight.)

Given the excessive loads being reported at the JRTC, it is understandable that soldiers would have difficulty remaining effective in combat following extended periods of carrying such heavy loads.

Some solutions to this problem include developing lighter weight components, using special load-handling equipment, reevaluating current training doctrine, and designing better load planning models. There is also a fifth possibility—developing specific physical training programs that will better condition soldiers to tolerate carrying heavy loads. This is the approach the U.S. Army Physical fitness School has taken in an attempt to improve the ability of soldiers to carry their mission essential equipment.

The traditional Army physical training programs often revolve around aerobic training (running) and calisthenic-type activities. More recently, resistance (strength) training has also been emphasized. Running and the other aerobic activities are best for improving cardiovascular fitness and allow soldiers to perform physically at a lower relative exercise i1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_1-2_700px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_3-4_300px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_5_300px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_6-7_700px.jpgntensity and for longer periods. In addition, soldiers with high levels of cardiovascular fitness recover more quickly from exhausting exercise. Calisthenic activities may improve muscle strength and endurance the first few weeks of training, but further improvements are generally slight without adequate overload. As evidenced by recent experiences in the Falklands and Grenada, such traditional training programs are not enough to improve the ability of soldiers to carry heavy loads over long distances.

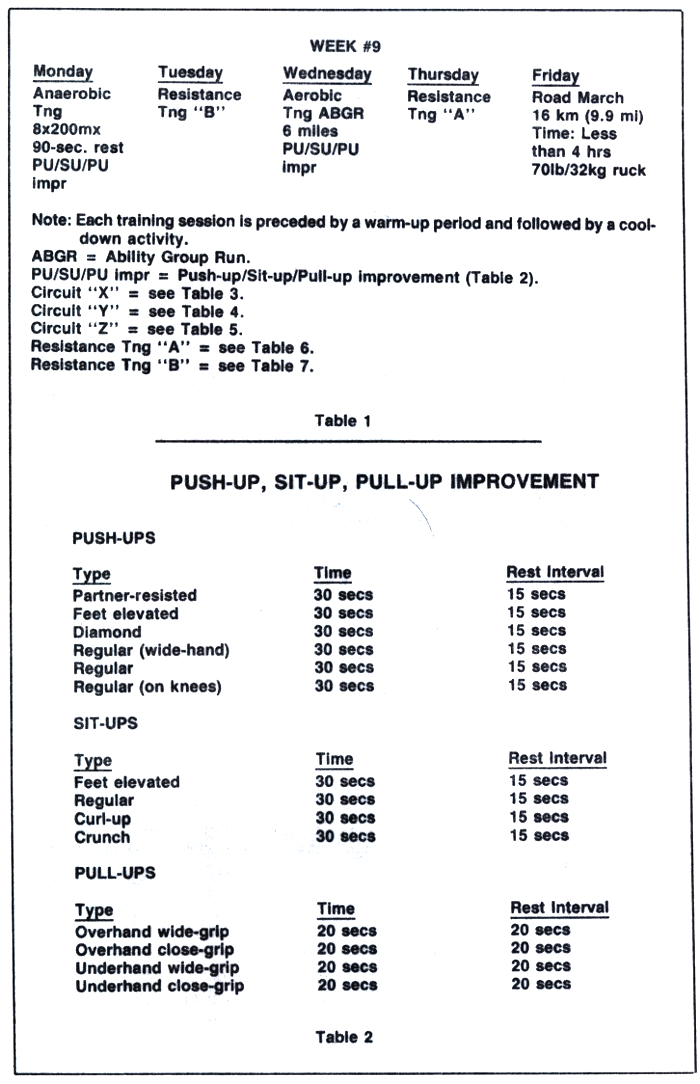

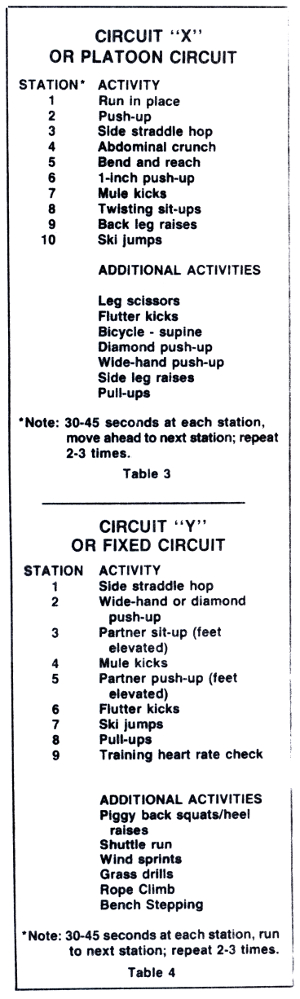

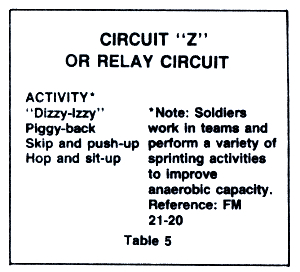

The physical training program presented in Tables 1-7 is designed primarily to improve load carrying ability (road march performance) in a light infantry unit, It is based upon our experience with soldiers from the 2d Battalion, 17th Infantry. Fort Richardson, Alaska, who took part in a nine-week physical training program designed to improve the basic components of the soldiers' physical fitness (aerobic and anaerobic capacity, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and body composition) and improve their load carrying ability.

The program is conducted daily, Monday through Friday, for nine weeks. Generally, one day a week is devoted to resistance training (partner-resisted exercises. strength training equipment, push-up/sit-up/pull-up improvement, and the like), one day to cardiovascular training (ability group run), one day to anaerobic training (sprints, relays), and one day to circuit training (calisthenic, relay, sandbag). On alternate weeks, the fifth day is devoted to road marching and unit runs.

All of the training is progressive in that both the intensity and the duration of the training increase from one session to the next Most of the training sessions can be done within one hour, and they require little or no equipment.

Before beginning the program, leaders should familiarize the soldiers with the physical training activities that will be conducted during the first week. This session should cover procedures for proper warm-up and cool-down as well as the proper techniques for cardiovascular and strength training.

A "one repetition of maximum" (1RM) test should also be administered on each strength training exercise. Determining a 1RM involves progressively and systematically increasing the weight a soldier tries to lift until he reaches a weight he can no longer lift. The last weight he successfully lifts, using the correct technique, is the 1RM for that exercise.

Resistance training includes, whenever possible, doing three sets of 8 to 12 repetitions at 70 to 85 percent of the 1RM. The specific strength training exercises described here improve the muscles that are directly involved in load carrying.

The weight training exercises include the squat, the heel and leg raise, the knee extension and curl, the bench press, bent-over rowing, the shoulder press and shrug, and the arm curl and extension. These exercises may be performed using various weight training machines or free weight equipment. When a soldier can consistently complete more than 12 repetitions on his final set, the resistance should be increased.

1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_1-2_700px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_3-4_300px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_5_300px.jpg 1990_Load_Carrying_Ability_tables_6-7_700px.jpgDuring the push-up/sit-up/pull-up improvement sessions, the soldiers should perform several types of each exercise. We also recommend they do a single set of partner-resisted, feet elevated, diamond, wide-hand, regular, and from-the-knee push-ups. Sit-up variety includes feet elevated, regular, curl-up, and crunch types. They should also do wide-grip and close-grip pull-ups and chin-ups.

The soldiers should run in ability groups. The groups are initially determined by the performance of the soldiers on the Army Physical fitness Test (APFT) that is administered during the first week. (The test is administered again midway through the training program to determine the soldiers' improvement.) At first, they should run three miles and progress about ten percent each week up to six miles in the ninth week. Anaerobic or interval training begins with six repeats of 100 meters with a 45-second rest period between sprints and progresses to eight repeats of 200 meters with a 90-second rest period between sprints. The soldiers should run the sprints with the greatest possible effort.

The soldiers should road march regularly during the training program. The load they carry, the distance they cover, and the duration of these training road marches should be progressively increased just as the other physical training activities are. We recommend an initial distance of five miles (eight kilometers) with 30-pound sandbag-filled rucksacks. This may be modified, however, on the basis of the physical fitness levels of the soldiers at the beginning of the program. The final road march training distance is ten miles (16 kilometers) with 70-pound rucksacks. The data collected during the Alaska study indicate units with sound five-day-per-week physical training programs can improve and maintain their road march ability by conducting as few as two road marches a month.

Load bearing by infantry soldiers is a critical part of combat operations. But overloading these soldiers can lead to excessive fatigue, detract from their ability to fight, and may even determine the success or failure of a mission.

Commanders must make wise decisions in determining which equipment their men must carry. But they must also provide their troops with the necessary physical training so they can carry heavy loads without undue fatigue. When it becomes necessary to carry heavy loads, soldiers who have been properly conditioned to carry them will arrive at the battlefield less fatigued and better able to fight than those who have not been conditioned.

Michael S. Bahrke, who holds a PhD, is Director of Research at the Physical fitness School, He is a research psychologist with an extensive background in human factors research.

Lieutenant Colonel John S. O'Connor, an Infantry officer, is Director of Training at the U.S. Army Physical fitness School, Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana. He has served in a variety of infantry units including service in Vietnam. He holds a PhD in Exercise Physiology.

- The O'Leary Collection; Medals of The Royal Canadian Regiment.

- Researching Canadian Soldiers of the First World War

- Researching The Royal Canadian Regiment

- The RCR in the First World War

- Badges of The RCR

- The Senior Subaltern

- The Minute Book (blog)

- Rogue Papers

- Tactical Primers

- The Regimental Library

- Battle Honours

- Perpetuation of the CEF

- A Miscellany

- Quotes

- The Frontenac Times

- Site Map

QUICK LINKS

- The Service Kit of the Infantry Soldier (1901)

- The Load Carried by the Soldier (1921)

- The Equipment of the Infantry Soldier In the Light of War Experience (1923)

- The Mobility of One Man (1949)

- Keep The Doughboy Lightly Loaded (1950)

- The Soldier's Load (1955)

- The Accoutrements of the British Infantryman, 1640 To 1940

- A Soldier's Load (1987)

- The Soldier's Load; Planning Smart (1990)

- Soldier Load; When Technology Fails (1987)

- Load Carrying Ability (1990)

- Roadmarching and Performance (1990)

Soldier's Load posts on The Minute Book (blog)

- Soldiers Load (Canadian Militia, 1870)

- The Soldier's Load — The RCR at Vimy Ridge

- FSPB 1914 — Dismounted Soldiers

- Germany 1900-1914

- The Lewis Gun Section (1925)

- Platoon Weapons and Ammunition (1942)

- A historic problem

- The Soldier's Load (1871)

- A Soldier's Load

- The Infantry Platoon; 1942

- Dress and Equipment (1918)

- Soldier's Load; North Africa

- The Soldier's Load; Vietnam

- Factors Causing Soldiers' Overload

- The Soldiers Load; Australia

- The Soldier's Load in Vietnam

- Soldiers' Load — US Army — 1916

- Burden Put on Doughboy

- Sending Men to Death by Overloading

- To Test New Equipment (US Army, 1911)

- Exhaustible Infantry

- What a Soldier Carries

- The Burden the Soldier Boy Carries (1918)

- Japanese Soldier's Load (1910)

- Heaviest Laden Pack Animal in American Army

- Soldier's Kit in South Africa

- [US] Army Tries to Reduce Pack Weight (1963)

- The Soldier's Kit (1932)

- With a 70-Pound Pack (US Army, 1925)

- The Soldier's Load, Canadian Militia (1868)

- Commando Arms and Equipment