Topic: Humour

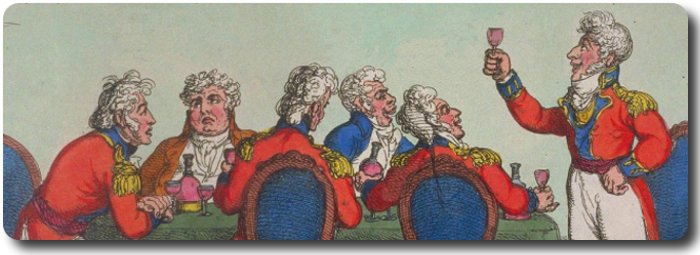

Advice to Officers

Gallant Gentlemen; a portrait of the British Officer 1600-1956, E.S. Turner, 1956

One of the most telling, and enduring, satires at the expense of the British officer appeared in 1782. It is attributed to Francis Grose, a one-time adjutant of militia. His Advice to Officers of the British Army has been reprinted many times, and deservedly

Admirably pinned down is the subaltern, whose failings change but slightly from one generation to another. In his advice to commanding officers, the writer says:

"The subalterns of the British army are but too apt to think themselves gentlemen; a mistake which it is your business to rectify. Put them, as often as you can, upon the most disagreeable and ungentlemanly duties; and endeavour by every means to bring them upon a level with the subaltern officers of the German armies."

Then the writer offers his advice to subalterns:

"The fashion of your clothes must depend on that ordered in the corps; that is to say, must be in direct opposition to it: for it would show a deplorable poverty of genius if you had not some ideas of your own in dress.

"Never wear your uniform in quarters, when you can avoid it. A green or a brown coat shows you have other clothes besides your regimentals, and likewise that you have courage to disobey a standing order…

"If you belong to a mess, eat with it as seldom as possible, to let folks see you want neither money nor credit. And when you do, in order to show that you are used to good living, find fault with every dish that is set on the table, damn the wine, and throw the plates at the mess-man's head … if you have pewter plates, spin them on the point of your fork, or do some other mischief, to punish the fellow for making you wait.

"When ordered for duty, always grumble and question the roster. This will procure you the character of one that will not be imposed on.

"Never read the daily orders. It is beneath an officer of spirit to bestow any attention upon such nonsense … it will be sufficient to ask the sergeant if you are for any duty.

"When on leave of absence, never come back to your time; as that might cause people to think that you had nowhere to stay, or that your friends were tired of you."

No rank or category of officer escapes without a well-placed barb in a tender spot. For example:

The aide-de-camp: "Let your deportment be haughty and insolent to your inferiors, humble and fawning to your superiors, solemn and distant to your equals."

The quartermaster: "The standing maxim of your office is to receive whatever is offered you, or you can get hold of, but not to part with anything you can keep."

The surgeon: "Keep two lancets, a blunt one for the soldiers and a sharp one for the officers: this will be making a proper distinction between them."

The paymaster: "Always grumble and make difficulties when officers go to you for money that is due to them: when you are obliged to pay them endeavour to make it appear granting them a favour, and tell them they are lucky dogs to get it."

The chaplain: "At the mess always provide yourself with a spare plate to secure a slice of pudding, pie or other scarce article which else might vanish before you were ready for it; for the good things of this world are of a very transitory nature, particularly at a military mess."

The adjutant: "When at any time there is a blundering or confusion in a manoeuvre, ride in amongst the soldiers, and lay about you from right to left. This will convince people that it was not your fault."

The major: "In exercising the regiment, call out frequently to the most attentive men and officers to dress, cover or something of that nature: the less they are reprehensible, the greater will your discernment appear to the bystanders, in finding out a fault invisible to them."

No one who has served in the Army can have failed to see the latter technique applied--more usually by sergeant-majors and drill sergeants.

The satirist, it will be seen, uses the phrase "If you belong to a mess." By no means all regiments kept up an officers" mess as it would be recognised today; such communal life as the officers enjoyed was usually found in taverns. The mess proper was largely a nineteenth-century growth. A general who inspected the Buffs in 1774 wrote in his report: "The officers eat and live together in friendship, Major Nicholson excepted." No clue is given as to why Major Nicholson was thus invidiously named. It may be that he had taken to himself a wife, but as a major he would be perfectly entitled to do so.