Sea-Soldiers (1887)

Topic: Marines

Sea-Soldiers (1887)

"Marines" in the American and British Navies

Montreal Daily Witness, 26 July 1887

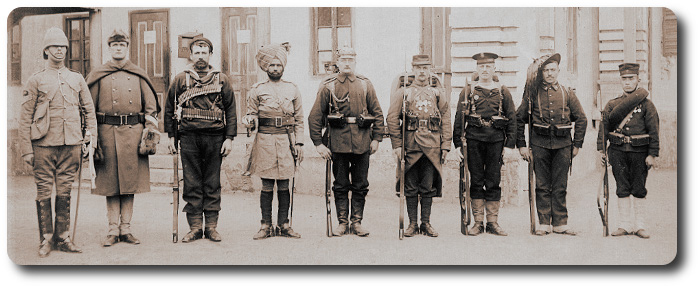

Neither at home nor in this country is the general public so well acquainted with the marine forces as it is with the army or navy. But the British marines are indeed a credit to their country, and are generally allowed to be as fine as, of not finer, than any other branches of the service, with the exception, perhaps, of Her Majesty's Guards. Today, in Montreal, the United States marines are well represented on board the U.S. Man-of-War "Galena," and the visitor only needs to enter into conversation with them to find out what a smart and intelligent body they are. They muster but twenty-six, with one officer, Lieutenant B.R. Russell, in command, through whose courtesy the writer was enabled to find out a good deal of the interior economy, discipline, etc., of this fine corps. The "Galena" was present at Alexandria after the pillage and burning of the city, and at the bombardment; but Lieutenant Russell is the only officer on board the ship to day who was serving with her at that time. A detachment of sixty American marines was chivalrously sent by Admiral Nicholson to act with the Royal Marines of the British squadron, but their efforts were confined to putting down the plunderers and incendiaries,—after which they returned to their own ships. The "Galena" was afterwards ordered to South America.

Neither at home nor in this country is the general public so well acquainted with the marine forces as it is with the army or navy. But the British marines are indeed a credit to their country, and are generally allowed to be as fine as, of not finer, than any other branches of the service, with the exception, perhaps, of Her Majesty's Guards. Today, in Montreal, the United States marines are well represented on board the U.S. Man-of-War "Galena," and the visitor only needs to enter into conversation with them to find out what a smart and intelligent body they are. They muster but twenty-six, with one officer, Lieutenant B.R. Russell, in command, through whose courtesy the writer was enabled to find out a good deal of the interior economy, discipline, etc., of this fine corps. The "Galena" was present at Alexandria after the pillage and burning of the city, and at the bombardment; but Lieutenant Russell is the only officer on board the ship to day who was serving with her at that time. A detachment of sixty American marines was chivalrously sent by Admiral Nicholson to act with the Royal Marines of the British squadron, but their efforts were confined to putting down the plunderers and incendiaries,—after which they returned to their own ships. The "Galena" was afterwards ordered to South America.

Lieutenant Russell related how a lot of the officers of the ship barely escaped with their lives during this exciting an perilous time. Having gone ashore in uniform, they had to be sent plain clothes from the ship in order to insure their escape. They took 360 refugees of all classes on board, among them forty Americans missionaries. Not being able to accommodate any more, a merchant ship was chartered to aid in relieving the sufferers.

The total strength of the United States Marine Corps is 2,500 of all ranks. Unlike Britain, they have no marine artillery, but merely the light infantry corps. However, they act the same as the marine artillery when required to do do, and besides infantry tactics they are thoroughly instructed in gunnery, serving on land as well as at sea. In the States the marines have barracks at Brooklyn, Washington, Boston, Portsmouth (N.H.), and Portsmouth (Virginia), Mure Island (California), Annapolis (Maryland), and Philadelphia. In Britain the marines number five thousand men and 250 officers, and there are four places where they have barracks:—Marine Artillery (Eastney) at Portsmouth, and Marine Light Infantry at Gosport, Chtaham and Plymouth. The Marine Artillery Barracks at Eastney is a magnificent building, capable of holding 2,500 men, and is fitted up regardless of expense,—perhaps the finest barracks in England. The U.S. Marines are very proud—and justly so—of their splendid band, consisting of fifty pieces. It is quartered at Washington, and is admitted to furnish about the best military music in the States. The band of the marines at home would be difficult to beat, and is equal to any other, with the exception, perhaps, of the Royal Artillery at Woolwich. But this is not to be wondered at, the Marine divisional bands never leave their headquarters, and there are 250 officers to subscribe to keep them up. It is the same with the Artillery, Engineers' and Guards' bands. Some 2,500 officers of Artillery subscribe to the band at Woolwich, which never leaves that town.

The promotion of the United States marine officer is certainly remarkably slow compared with that of his British cousin. Lieutenant Russell has now seen eighteen years service, and before he gets his captaincy he expects to have served another three of four years as first lieutenant; but compared with other countries the pay of officers and men in the marines, in the army, and in then navy of the States is very good. A lieutenant gets $1,500 a year, and all officers an increase of 10 percent every five years up to 40 percent. After this, if they have not already got it, the must await promotion. A captain gets $1,800 a year, whereas an English captain's pay is only eleven shillings and seven pence a day, and a lieutenant's six shillings and sixpence (about $1,015 and $570 a year respectively). A second lieutenant in the United States marines gets $1,100 a year, and the private is far better off than the British marine. He receives $13 a month and everything found him; besides $209 every five years for clothing, out of which he can easily save at least $80. He has to serve three years at sea and two years in barracks; and, should he re-enlist for another five years, he will get $17 per month; but he must re-enlist within thirty days and will then forfeit no pay for absence. The private marine has $12.80 clear every month, as there is only one charge, and this is made to every one, officers, non-coms. and men,—viz. 20 cents for hospital,—whereas the soldier at home (provided he is particularly careful and well behaved) can barely clear eightpence a day out of his shilling, as he is deducted thee pence halfpenny daily for groceries and one half-penny for washing.

There are several men on board the "Galena" who have served Her majesty,—mostly in the infantry,—and they all speak highly of their treatment by the United States Government. The discipline is by no means so severe as it has been in the English service, and courts-martial are rare occurrences. No grog is allowed on board ship, but in barracks the men have canteens where they can run credit, up to the amount of six or seven dollars a month,—only receiving their pay monthly. The promotion to the rank of non-commissioned officer is rather rapid, for the reason that once a man is reduced he cannot be again promoted during the period of that enlistment; and a non-com. can be reduced without the usual court-martial, but merely by an order from the Colonel Commandant. Most of the marines on board the "Galena" are Irish and Irish Americans, with a few Germans. On no account is flogging resorted to by the United States authorities, nor branding of any kind; but, as regards this, things are better now in the British service than they were some few years since, and the British army owes many a debt of gratitude to the Duke of Cambridge—but none greater than for the "instructions" on corporal punishment recently issued by the War Office. In his younger days the Duke bore a reputation of being a rigid martinet, but the army papers at home say that he has the good sense to see that short service has brought an entirely new situation into existence. It is not merely that a much larger number of recruits must be attracted into the service to make good retirements, nor even the consideration that unless military life be made tolerably pleasant the soldiers will revert to civilian existence as son as their first term expires. The main reason for relaxing the code of discipline in a certain degree is that, the more constantly a young soldier undergoes punishment, the less chance is there of his ever becoming thoroughly efficient. The Commander in Chief accordingly instructs commanding officers to resort to courts-martial less frequently, while these latter tribunals are cautioned to temper justice with mercy to a greater extent than at present. The general annual return of the British army records show that in 1886, no less than 8,000 courts-martial were held, and 150,000 minor punishments were entered inti the defaulters' books. Such a thing as promotion from the ranks to a commission in the United States marines is unheard of. The aspirant to the rank of officer of marines must go to the Naval College of Annapolis between the ages of 14 and 18, and six years afterwards must make a final examination, having in the mean time spent two years at sea. He will then be appointed, if he passes the severe examination, either to the navy or marines as vacancies occur.

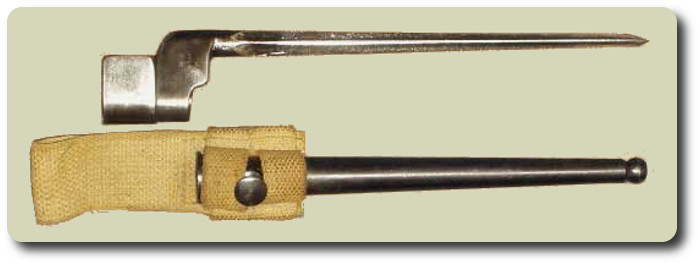

The marines are considered the corps d'elite of the American service, and, therefore, appointments are much sought after. The uniform is neat and serviceable, though not showy, and the equipment good; they carry the Springfield rifle, sighted up to 1,400 yards, 45 calibre, and bayonet; but the sailors carry the Hotchkiss rifle, which contains five rounds in the magazine and one in the chamber, and they are armed with a cutlass. Since the last administration in the United States, general officers have been abolished in the United States marines, and now they have merely a colonel-commandant, and the divisions in barracks are officered as a regiment of the line, carrying colors, etc., and all field officers are mounted; but the surgeons are detailed from the navy. The marine officer on board messes with the senior officers of the ship.

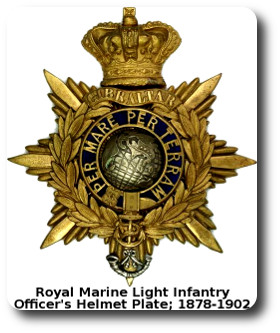

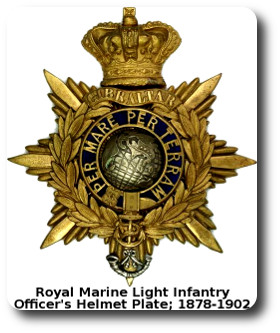

A word about the origin of the British marines. The first document referring to a special body of soldiers for service afloat appeared on the 26th October, 1664, in the reign of Charles II, authorizing 1,200 soldiers to be raised and distributed in His Majesty's fleet, and which were to be as one regiment, to be divided into six companies of 200 men each, and to be armed with fire-locks. Historians of the marine forces agree that the first corps specially set apart for sea service was the 3rd Regiment of the line (raised in 1663), and which in 1684 received the titles of the Duke of York and Albany's Marine Regiment. The uniform was yellow, lined with red, and their colors bore the cross of St. George, with the sun's rays issuing from each angle. In 1689 they went to Holland and joined the 2nd Foot Guards, and were called Prince George of Denmark's Regiment. By its reduction they became the 3rd Foot, now the celebrated 3rd Buffs, or, according to the army reform, "the Buffs or East Kent Regiment." From this corps the Royal Marines claim descent, and they share with the Buffs the privilege of marching through the city of London with colors uncased and drums beating. In 1755 fifty companies of marines were raised, and were stationed at Chatham, Portsmouth, and Plymouth, and since then there has always been a corps of marines in the peace establishment. In 1855 Her Majesty was please to approve the infantry division being styled the "Royal Marine Light Infantry," for their service in the Crimea.

Now that the United States marines are here, it may be of interest to know that three marine regiments were raised in new York in 1740, and were clothed in "camlet coats, brown linen waist coats and canvas trousers." At the present time the uniform of the English marine is similar to that of the line, with blue facings. The badges of the Royal marine forces (artillery and light infantry) are "The Globe," with the motto, "Per mare, per terram," the crown, the anchor and the laurel; Her majesty's cypher. H.R.H the Duke of Edinburgh is their colonel. The marines have upheld the honor of their country and gained distinction in every portion of the globe; and it is only necessary to read the papers to tell how the marine battalions and camel corps employed during the late Egyptian war and in the Soudan were the admiration of all for their "gallant bearing, splendid physique and admiral discipline." The last time the writer had a chance of seeing the American marines was at Portsmouth in 1869, when he was adjutant of the 46th Regiment, and was on duty at the Dock Yard with that corps when the Americans sent their man-of-war to England to convey the body of the world renowned philanthropist, the late Mr. Peabody, back to his native land, the remains being escorted to this side of the Atlantic by the British man-of-war "Warrior," on the deck of which ship the body lay in state until the arrival of the American man-of-war in Portsmouth.

R.B.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

The dispatches from General McClellan's army have several times spoken of a "regular bayonet charge." The pride of the English army has been in bayonet force.—But the dispatches state something unusual, and which must be considered complimentary to the enemy as well as to our own soldiers. We allude to the remark that the enemy were driven a mile, "during which one hundred and seventy-three rebels were killed by the bayonet alone." It is a very rare occurrence that men stand the approach of a well directed bayonet charge, and it is understood that the highest courage and daring are necessary to resists it. There are stories extant of regiments meeting bayonet to bayonet, and crossing weapons. But we do not find any authemtication of these. One favorite military anecdote relates that an English and a french regiment once met in that way and stood pressing against each other without wounding a man for a full half hour. In the Mexican war we carried several important points "with the bayonet," but this was seldom with any direct heavy charge in line.—We once asked a distinguished officer whether one of those charges was an old fashioned bayonet charge in solid rank.—He laughed and said it was very different. When the word "charge" was given the men started on a run, yelling and shouting, and throwing off all encumbrances as they ran. The very appearance of a body of furious tiger-like men, approaching at a full run, and making the air hideous with their cries, frightened the enemy from his position, and it was seldom that a man had a chance to touch another with his bayonet.

The dispatches from General McClellan's army have several times spoken of a "regular bayonet charge." The pride of the English army has been in bayonet force.—But the dispatches state something unusual, and which must be considered complimentary to the enemy as well as to our own soldiers. We allude to the remark that the enemy were driven a mile, "during which one hundred and seventy-three rebels were killed by the bayonet alone." It is a very rare occurrence that men stand the approach of a well directed bayonet charge, and it is understood that the highest courage and daring are necessary to resists it. There are stories extant of regiments meeting bayonet to bayonet, and crossing weapons. But we do not find any authemtication of these. One favorite military anecdote relates that an English and a french regiment once met in that way and stood pressing against each other without wounding a man for a full half hour. In the Mexican war we carried several important points "with the bayonet," but this was seldom with any direct heavy charge in line.—We once asked a distinguished officer whether one of those charges was an old fashioned bayonet charge in solid rank.—He laughed and said it was very different. When the word "charge" was given the men started on a run, yelling and shouting, and throwing off all encumbrances as they ran. The very appearance of a body of furious tiger-like men, approaching at a full run, and making the air hideous with their cries, frightened the enemy from his position, and it was seldom that a man had a chance to touch another with his bayonet.

1. His Excellency the Administrator of the Government and Commander-in-Chief, having had under consideration the possibility that raids or predatory incursions on the Frontier of Canada, may be attempted during the winter, by persons ill disposed to Her Majesty's Government, to the prejudice of the Province and the annoyance and injury of Her Majesty's subjects therein;

1. His Excellency the Administrator of the Government and Commander-in-Chief, having had under consideration the possibility that raids or predatory incursions on the Frontier of Canada, may be attempted during the winter, by persons ill disposed to Her Majesty's Government, to the prejudice of the Province and the annoyance and injury of Her Majesty's subjects therein;

Hollywood, Cal.—(AP)—If there should be another world war tomorrow the doughboys drawn from Hollywood would astonish the military experts.

Hollywood, Cal.—(AP)—If there should be another world war tomorrow the doughboys drawn from Hollywood would astonish the military experts.

Neither at home nor in this country is the general public so well acquainted with the marine forces as it is with the army or navy. But the British marines are indeed a credit to their country, and are generally allowed to be as fine as, of not finer, than any other branches of the service, with the exception, perhaps, of Her Majesty's Guards. Today, in Montreal, the United States marines are well represented on board the U.S. Man-of-War "Galena," and the visitor only needs to enter into conversation with them to find out what a smart and intelligent body they are. They muster but twenty-six, with one officer, Lieutenant B.R. Russell, in command, through whose courtesy the writer was enabled to find out a good deal of the interior economy, discipline, etc., of this fine corps. The "Galena" was present at Alexandria after the pillage and burning of the city, and at the bombardment; but Lieutenant Russell is the only officer on board the ship to day who was serving with her at that time. A detachment of sixty American marines was chivalrously sent by Admiral Nicholson to act with the Royal Marines of the British squadron, but their efforts were confined to putting down the plunderers and incendiaries,—after which they returned to their own ships. The "Galena" was afterwards ordered to South America.

Neither at home nor in this country is the general public so well acquainted with the marine forces as it is with the army or navy. But the British marines are indeed a credit to their country, and are generally allowed to be as fine as, of not finer, than any other branches of the service, with the exception, perhaps, of Her Majesty's Guards. Today, in Montreal, the United States marines are well represented on board the U.S. Man-of-War "Galena," and the visitor only needs to enter into conversation with them to find out what a smart and intelligent body they are. They muster but twenty-six, with one officer, Lieutenant B.R. Russell, in command, through whose courtesy the writer was enabled to find out a good deal of the interior economy, discipline, etc., of this fine corps. The "Galena" was present at Alexandria after the pillage and burning of the city, and at the bombardment; but Lieutenant Russell is the only officer on board the ship to day who was serving with her at that time. A detachment of sixty American marines was chivalrously sent by Admiral Nicholson to act with the Royal Marines of the British squadron, but their efforts were confined to putting down the plunderers and incendiaries,—after which they returned to their own ships. The "Galena" was afterwards ordered to South America.

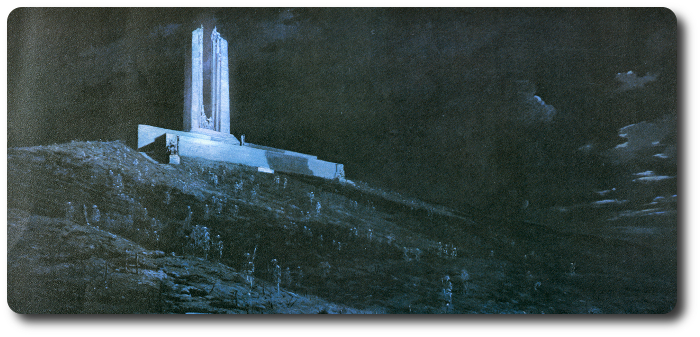

April 9, 1917, was Easter Monday.

April 9, 1917, was Easter Monday.