Terms of Enlistment, 1905

Topic: Canadian Army

Permanent Force

Terms of Enlistment, 1905

Boston Evening Transcript; 8 May 1905

Extracted from: Garrisoning Halifax

By: E.W. Thomson

(Special Correspondence of the Transcript)

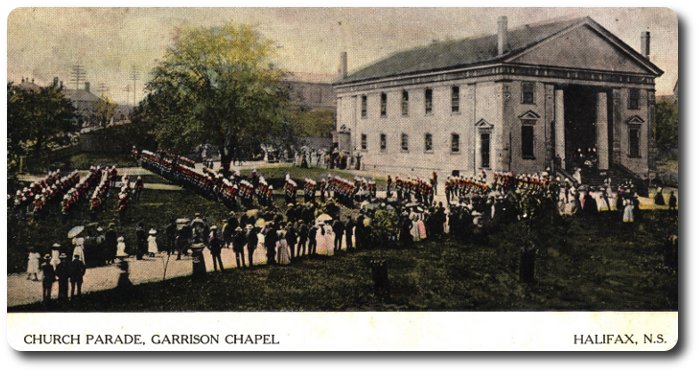

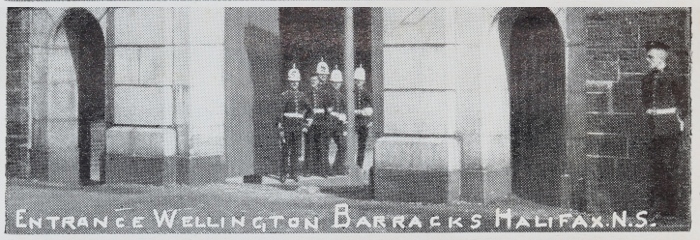

Recruits for the "Forces" may choose between cavalry, mounted rifles, field and garrison artillery, engineers, infantry, army service corps and army medical corps. Fancy a couple thousand men being enough to "go round" all these branches! The pay is 50 cents per day for privates and gunners for the first three years, or one term of enlistment, 60 cents for the next three years, and 75 cents thereafter. A master gunner at headquarters is to get $1 for his first three years in rank, $.25 the next three years, and $2.50 subsequently. Between his pay and that of the privates are a large variety of rates, according to rank and service and corps.

The terms of enlistment are about as good as those offered to United States regulars. Of course they include free rations, free quarters, and free medical attendance. In the Canadian soldiering trade an economical, sober man will be able to save ten or twelve dollars a month. Few young laborers, or even mechanics, can count on saving more. The life offers a sort of career, not unattractive even in a pecuniary sense, the chances of promotion being considered, with the certainty of a substantial pension for long service. By a wise provision, the good conduct pay is deferred, and lumped to the man on discharge, that he may have something to start his civilian career with. Lest too many American college graduates should flock over here to enlist, it may be observed that none but bona fide British subjects are admitted to the privilege.

It is not so attractive to able-bodied common schooled young Canadians as the West seems, but some of them, who do not feel keen for the competitive life, have joined. Probably the forces of Canada will become, as the Northwest Mounted Police tends to be, recruited largely from young old country immigrants. The Briton inclined to life as a Tommy, can get in the Canadian service more than twice as much as John Bull will give him for joining the thin red line of 'eroes. He can come out to enlist in Canada for practically nothing, since an allowance of $10 for travelling expenses is made, and steerage passage could be had for that, or less, last year.

An impression that the Ottawa Government ought to give better pay prevails among those who wish that the tiny Canadian regular "nucleus" should be national in the Canadian sense, and as the Mounted Police has been, as good as, if not better than, anything of its kind in the world. The brisk, hard, dour, efficient young Canadian, something of a presician, orderly, almost diabolically bent on suppressing the "bad man," is a type that reminds one of the young puritan trooper whom Kingsley sketched in one short passage of immortal prose. That young Canadian will be deterred from enlistment, not altogether by the poor pay, but by the sort of company that the poor pay will enlist. Widening the field of choice, so that the "good character" proviso might be most rigidly insisted on, would add one-half to, or double the pay. Then the men accepted might be highly intelligent, moral, and as efficient as twice their number of wastrels.

If there is anything more clear than another about the composition of modern armies it is that the human material ought to be of the best kind procurable for such service. Not only in the field, but in times of peace, one regiment of the first class is an example and inspiration to all who see its work, its life. Such a regiment may elevate the national conception of the regular, profoundly affect for good the morale of the volunteer, hugely influence to enlistment and to heroism the classes that now rather shun soldiering as a ruffianly trade. It seems a mistake for Canada not to cut wholly loose from the Old Country ideal of the regular, as a poor devil, kept on beggarly pay, and not fit to be allowed into respectable company. The ideal on which Cromwell raised the new model would pay better all round.

The reputation of the Dominion, to enhance which great sums are spent in advertising, would be advanced throughout the world if military men could truly say "Canada does this thing extremely well." This country needs nothing so much as the kind of pride which would thus be considerably fostered. Even as a matter of dollars and cents it would pay to make the "nucleus" exceedingly good, for its spirit, its economies, its efficiency, its perfect appearance, collectively and individually, the high character of its men and officers, would react on the entire volunteer force, and on the general population, too. It is a great thing to make a people proud of doing a difficult thing admirably. If the Government would appeal to this spirit, which was one of the best elements that contributed to the general regret for Lord Dundonald's departure, the people would respond heartily. Of course it would be necessary that the administration of the imagined, ideal little force should be high-minded and altogether devoted. That sort of administration cannot be got for a force conceived on a makeshift ideal. Sir Frederick Borden, the minister of militia, seems a big enough man to rise to the height of the argument, and Sir Wilfred Laurier is just the one to see the scheme put through in right shape, if once it fires his fine imagination.

There would be little use setting out on such a scheme, unless the remodelling of the uniform and equipment of the Canadian new model were patterned without the usual limitation of the British forces. In color, cut, texture, ease, the British soldier's garb is all wrong, and often idiotically so. His tight tunic, his comically useless forage cap, his clumsy boots, his belts, and buttons, and tightenings—they embarrass poor Tommy—they show that they were devised by a lot of military grannies who thought mainly of parade appearance and economy. The campaigning uniform of the American soldier is the real thing in comfort, and also in appearance, at least to those who think that nothing looks so well as what conforms to an ideal of efficiency. If the Canadian soldier were put into the hodden gray of his country, loosely made, and delivered from every vestige of the old "Fuss and feathers and button" aspect, he would present the appearance suitable to his work. Of course it scarcely matters a rap what garb you put on the sort of men who are apt to enlist in a low-paid, imitation-English force.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

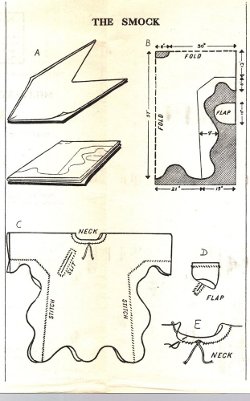

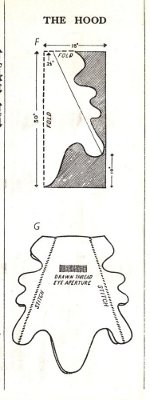

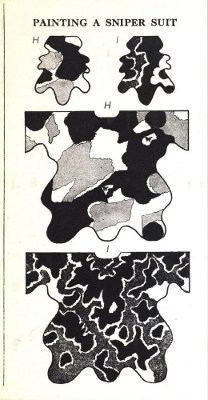

Extracted ftom the Canadian Army Manual of Training; Survival Operations (1961), (Revised May 1962); CAMT 2-91

Extracted ftom the Canadian Army Manual of Training; Survival Operations (1961), (Revised May 1962); CAMT 2-91