Exhaustible Infantry

Topic: Soldiers' Load

Exhaustible Infantry

Commentarty of Infantry Operations and Weapons Usage in Korea, Winter of 1950-51, S.L.A. Marshall, October 1951

In the Korean fighting, the average combat soldier, when his total load is somewhere between 38 and 45 pounds (including clothing), gets along fairly well and can march a reasonable distance, engage, and still remain relatively mobile. When the load goes above 50 pounds, he becomes a drag upon the company.

Fighting Load

In the attack, the infantryman carries his weapons, ammunition, intrenching tool, filled canteen, and first-aid pack. This is the shake-down infantry load in Eighth Army operations. Because of the steepness of the ridges, and the fatigue which comes of climbing prior to engagement, such things as rations and bedding, usually regarded as "necessities" for the fighting man, are not carried forward by the attack force. Where the developments in the situation and the availability of support personnel permit it, food and bedrolls are got up to the attack force by supply parties somewhere along the course of the fight.

But often as not these arrangements are frustrated by an untoward course in the fighting. In consequence men go hungry and miss out on sleep. Neither shortage is regarded by the infantry within Eighth Army as a cruel and unusual hardship. The men take these things in stride, and when the pressure is eased and conditions are nearer normal again, they boast about what they have undergone. During the winter fighting, when the night temperatures were ranging between 5º and 20º, companies in the attack were not infrequently committed without overcoats or bedrolls, and minus rations, despite the tactical prospects being that supply in these things might not get up to them until the following morning.

They commonly appeared far more willing to risk a proportion of loss from frostbite than an endangering of the unit as a whole through failure of ammunition supply. The length of the approach march and the nature of the terrain occasionally permitted wearing either the overcoat or parka, or carrying the sleeping bag, but rarely both. Which it was to be was a matter for company decision. The battalion commands usually strove to get food and bedrolls forward to companies in the attack prior to darkness, though in fact the detail of this work would frequently fall upon the rear echelon of the company directly concerned. As often as not these efforts were thwarted by circumstances beyond anyone's control.

Ranks understood the problem and were not demoralized by the lack of food and warmth. They blamed no one; frequently they praised the earnest, but negative, effort of the supply parties which had failed them.

In the course of all of the critiques of Eighth Army infantry, though this situation was many times repeated, there was not one single instance in which troops took a bitter or complaining attitude when speaking of their comfort shortages during engagement. The universal reaction was: "That was how it happened. There was no help for it. We weren't hurt by it and we'll probably have to do the same thing again."

The Natural Load

The Korean research indicated that there is a natural limit imposed on what the average infantry soldier carries in fighting supply by what he has discovered about his own physical resources under varying conditions of stress. This is best judged by what happens within the average infantry company after it has been through repeated engagements, has shaken out all excess material, and has got down to fighting weight.

The infantry soldier will not carry more than two grenades, even though his senses tell him he is heading into a fight where grenades will be needed. In fact, though Korean operations are a grenade-using type of warfare, there was not found one infantry soldier in the whole of the Eighth Army who consistently carried more than two grenades. The average was slightly under two per man, since some individuals carried only one. The fatigue of the march was the determinant in this requirement. Decision as to what munitionment should be carried rested usually with the company commander, and after he became broken in he did not press men to carry more than they thought they could handle without risking exhaustion. It remained for the unit to take care of the reserve through company supply.

For men with carbines, the natural load was four clips; for men with Mls, between 94 and 120 rounds. These averages were general throughout all commands, and there was no marked deviation in any company unit. What loads were carried forward for the mortars and machine guns, etc., depended altogether upon the general circumstances, including how far the supply vehicles could drive forward and the availability of extra carriers. However, in the average circumstance the machine guns had 3 to 4 boxes of ammunition per gun, and the 60-mm mortars were supplied with between 50 and 100 rounds. BAR men averaged between 6 and 8 clips. Riflemen in the squad were markedly willing to carry extra ammunition for the BAR man.

Burden Limit

Weighing out this load of ammunition, along with the weapon, full canteen, uniform, etc., means that the average infantry fighter in Korea was carrying a handicap of approximately 40 pounds. This weight was sustainable, that is to say men so weighted could preserve tactical unity during an average march into enemy country, when fire was imminent. (A tabular discussion of march limits under fire conditions was included in Chapter IV.)

But it was also observed that among the men who were carrying weights in excess of 50 pounds there was an onset of straggling before the march was half completed. This served as a drag upon the general movement as other files peeled off to provide them with greater security. Solely because of the disproportionate weights, in an extended march it would sometimes be from 30 to 40 minutes after the head of the column had arrived on the objective when the tail closed in. These last to arrive would also be in the greatest state of fatigue. They included radio men, mortar ammunition carriers, mortar crews in general, and the flamethrower, though the latter's burden would have to be shifted from man to man in the course of the march because of its weight. The recoilless crews also did heavy labor, and were late in closing, if the march was extended.

Because mortar positions are characteristically in defilade, on low ground, to the rear of the defended ridgeline, this was not a frequent cause of tactical disarrangement in short marches. Its penalties became obvious only when infantry was put far across country over which organic transport could not follow because the country was unroaded.

Operations in Korea prove that Department of the Army and Office of Chief of Army Field Forces concern over the problem of the infantry burden is wholly justified, and that present staff processes and logistical arrangements fall seriously short of the standards requisite to providing our main fighting arm with an optimum mobility.

This problem has only a marginal solution. It cannot be solved in total. Infantry, by nature of its role in combat, must remain heavily burdened. The best that may be hoped for is that through re-examining our staff processes and reappraising our material and human resources, we can insure a system whereby the fighting load is made tolerable in the main.

When Korean operations began, we were no better prepared to initiate a sound economy within the infantry force than we were prior to World War I, despite the wealth of experience gathered meanwhile. The record shows that the expeditionary troops carried personal loads under which they could not fight and which they were in no position to store. Many of the items which they were compelled to carry were unsuited to the season; others were unsuited to fighting operations within the peninsula; still others were of questionable value at any time in any situation. Furthermore, during the winter operations, there was no sign that the supply staff within the replacement system had adjusted itself to the needs of the Korean fighting. Men struggled, and wore themselves down, carrying into the Theater items of equipment which were never used by the combat units. This applied especially to clothing issues. There was no indication that anyone had gone forward, studied what was being done on the ground, and then revised &pply procedures to conform with needs. The net result was that tactical commanders had to shake down the replacements, take away all of the unnecessary gear, and then either jettison it or find a place to store it. As invariably happens, whenever there is an impractical issue of equipment, time and personnel are wasted right down the line.

Most of this excess was thrown away a waste to the Army and to the American people. This wastage cannot be called the consequence of a bad supply discipline within the troops; it was due to faulty staff work and inadequate survey of the supply requirement by the command. Into the discard of items not really needed went also other items for which there was a genuine requirement a little later.

This is the invariable extra penalty which comes of serious overloading. Green troops do not have the ability to recognize what material is essential under the conditions of the fight. In the hour of emergency, they react only to what is needed for survival in the immediate situation. Therefore excessive loading will always lead to an undiscriminating shucking-off of the weight which presses them down. There is no safeguard against this except to load them properly in the first place.

Outfit by Popular Demand

As the Eighth Army became acclimated to its problem, the troops became knowing about their own main needs. Personal decision is probably the main influence in what the American infantry fighter carries along into battle of the multifarious supply in clothing, living and survival gear, and carrying equipment which are available to him. That may not be the way it should be, but that's how it works out in practice. If the majority of men don't want shelter halves, see no use in the light pack, and won't carry blankets when they see a chance to get sleeping bags, their feelings pretty much dictate how the unit ultimately is equipped. So it is that how the Army becomes outfitted after it has been long afield is pretty much a popular verdict on the utilitarian value of all equipage. And that verdict cannot be disregarded!

Under the stress of combat, such stock items as the meat can and the pack (the pack has proved highly useful in other wars but didn't meet the particular need in Korea) are found to be surplus weight, and so troops will not carry them forward. Too late the practical need for yet other items which had been thrown away in the early stages becomes recognized; they then have to be re-requisitioned.

In these particulars, Korea differs hardly at all from American experience in other wars of this century. But since it followed World War II by only five years, its main lesson might well be that an Army loses its "know-how" almost at the speed of light, and that the task of keeping staff procedures keyed up in the interim is far more complex than we think.

As the Eighth Army moved into the winter, its infantry forces did not remain overburdened; they were in fact traveling too light for the exigencies of the winter situation. Heavy weapons in the infantry line could not be assured a sufficient supply of ammunition. Troops in line often went hungry. The hilltop defenses had to get along without wire, mines, and tripflares. And so on.

Command Load

It must be said of the average regimental and battalion commander of infantry in Korea that he tends to carry along an excessive and extravagant load of personal equipment, and that any effort he may make toward encouraging his troops to lighten themselves for the furthering of mobility is therefore invariably at odds with his personal example. It is not enough that he must carry along a cot and sleeping bag; usually, he also carries an air mattress, pillow, spare bag, and several extra blankets. The quota is seldom one wash basin, one jerry can, one light, etc.; there will be several of each item. The same applies to trunk lockers and other dunnage. What the unit packs along for the comfort and convenience of the commander will probably be in average weight somewhere between 200 and 300 pounds. So long as one commander does it, and the excess is not reduced by any stricture from higher command, the others can be expected to follow suit. For social reasons there is a considerable rivalry about these things; one of the seeming satisfactions in command is the feeling of being relatively better off than one's fellows working at the same level. That is a human failing, but it is a failing none the less, when in field operations the services of more than one vehicle and the work of two or three men are required to shift the living gear of one officer every time that there is a displacement of the CP. With some of our commanders this was not necessary. They kept their gear at a minimum and had little more comfort than their troops. Still, this was not the common practice.

What Might Be Done

Toward the affording of partial relief to the troops in line, and the over-all strengthening of the defensive situation, there were two lines of approach which might have been taken by the staff, without looking beyond resources already at hand. They were:

- Organization of Korean porterage on a semimilitary basis, and

- Total coordination of all supplementary carrying resources within the Division structure to put them at the service of the battalions in the attack.

Neither of these approaches was immediately subjected to study and then The first was neglected despite its obviousness, probably given systematic application. because our Army is not colonially experienced and does not have an instinct for primitive methods. The second broad avenue was overlooked, perhaps because its prerequisite is a radical overhaul in American staff thinking. We bend over backwards in respecting the integrity of small-unit command and process within any larger component, seldom stopping to question whether the safety of all units might not depend finally on seeing the Division as a whole, and using its other parts to the utmost in an effort to get its fighting elements forward relatively fit and ready for the fight. The Regiment sweats to get its two battalions of the attack into the right ground, supplied with all that they need to fight and to endure. Meanwhile, at the rear, there are QM, Ordnance, and other service elements, with broad backs and many vehicles, and on that particular day they have no truly critical chores. To what extent better interior organization can improve the economy will never be known until it is put to the test. We make it work when confronted by a great emergency such as the Ardennes surprise. But we never attempt to apply the same principle in routine operations with the major purpose of conserving the fighting elements.

As a first step toward reform of the infantry supply problem, it is suggested that Logistics, basing upon the Korean supply studies, should proceed to categorize all infantry equipment as follows:

1. Equipment which must move with the infantry soldier in any fighting situation, such as his arm, canteen, aid pouch, ammunition belt, pants, boots, etc.

2. Equipment which he will have to carry personally in the interests of survival when subjected to extremes in climate, weather change, etc. These are kept in organizational supply and issued to him when required by the immediate conditions. They affect his personal responsibility and organizational logistics in that as his load increases; other means must be found for transporting the unit's residual weight.

3. Equipment composing the residual weight within the company (Mortar ammo in excess of a definite figure, mines, wire, etc.), which, while required in the fighting situation, cannot be manhandled by the company without excessive impairment of its fighting powers. The estimating of residual weights should be based upon the muscular potential in summer heat, or extreme winter cold, when the soldier is heavily weighted with his own clothing, and not upon what troops can do in temperate weather under the most favorable conditions. Once the residual weights are analyzed and described, all further procedure should be based on the assumption that when these materials cannot be moved to the scene of action by organic transport, it is the responsibility of higher command to make the arrangements by which they will be got forward for the benefit of the company.

4. Equipment which has proved impractical or of little utility under the stress of field conditions and should therefore be eliminated.

5. Equipment which has a practical purpose (such as the web cartridge belt) but is imperfectly suited to that purpose and should therefore be modified.

In the Korean fighting, the average combat soldier, when his total load is somewhere between 38 and 45 pounds (including clothing), gets along fairly well and can march a reasonable distance, engage, and still remain relatively mobile. When the load goes above 50 pounds, he becomes a drag upon the company. That was what was anticipated in theory and it has proved itself in practice. The calculating of the residual weight should assume an average 40-pound carry for the soldier. If, when that is done, such personal items as blankets, bedrolls, etc., cannot be fitted into the individual load, they should be classified as residual weight and it should be the duty of This was how it was handled many higher authority to arrange for their porterage. times during the winter fighting, except that already overburdened battalion and company commanders had to organize the makeshift arrangements.

Reform must begin at the top. Providing greater mobility to troops in the attack is primarily a problem for the division. The coordination of all division resources toward that end can be achieved only through the commander's staff. At first glance, it might be questioned whether this is a responsibility of G-3 or G-4. The best solution would require that they approach it jointly, with G-3 having the ultimate responsibility because of his closer tie-in with the daily progress of fighting operations and the peculiar authority which he exercises in this field. There is the capital risk that the experiment might be regarded as just another problem in transportation, routinely assigned to the division MT officer, and thereby die a sudden death.

As for the need that we do a better job in the analysis and use of all indigenous transport resources, our Korean failure is an example which commends itself to General Staff attention. The subject needs to be given continuing emphasis at Leavenworth, Benning, and at all other points where staff thinking is shaped. The same problem will certainly arise wherever we may engage in future. To be outnumbered on the fighting side in war becomes an insuperable handicap unless extreme ingenuity is used in the organization of all resources in meeting the logistical problem.

That we have exceeded all others in motorization but makes it more difficult for us to think about what can be done with animals and people. But the effort must be made, lest another opportunity be missed.

Posted by regimentalrogue

at 12:01 AM EDT

Sir Garnet Wolseley, the newly-appointed adjutant-general of the Imperial army, is well known to every Canadian, having been actively engaged as assistant quartermaster-general in Canada in 1870-71, and in the former year commanded the Red River expedition. Sir Garnet Wolseley is the eldest son of the late Major G.J. Wolseley, of the 25th Regiment of Foot, and grandson of the late Sir Richard Wolseley, Bart., of Mount Wolseley, in the county of Carlow, a member of the ancient house of Wolseley of Wolseley, on the county of Stafford, one of whose younger sons went to Ireland as a captain in King William's army, and who fought by the King's side at the battle of the Boyne, and was created a baronet for his service.

Sir Garnet Wolseley, the newly-appointed adjutant-general of the Imperial army, is well known to every Canadian, having been actively engaged as assistant quartermaster-general in Canada in 1870-71, and in the former year commanded the Red River expedition. Sir Garnet Wolseley is the eldest son of the late Major G.J. Wolseley, of the 25th Regiment of Foot, and grandson of the late Sir Richard Wolseley, Bart., of Mount Wolseley, in the county of Carlow, a member of the ancient house of Wolseley of Wolseley, on the county of Stafford, one of whose younger sons went to Ireland as a captain in King William's army, and who fought by the King's side at the battle of the Boyne, and was created a baronet for his service.

In the article referred to it is made to appear that the permanent corps cost the country the previous year in round numbers $476,000, while the remainder of the militia cost only $211,000; as the whole militia vote for that year was $1,360,000, it might have spoiled the writer's argument, but it would have been more satisfactory to some at least of his readers, if he had told what became of the remaining $672,000.

In the article referred to it is made to appear that the permanent corps cost the country the previous year in round numbers $476,000, while the remainder of the militia cost only $211,000; as the whole militia vote for that year was $1,360,000, it might have spoiled the writer's argument, but it would have been more satisfactory to some at least of his readers, if he had told what became of the remaining $672,000.

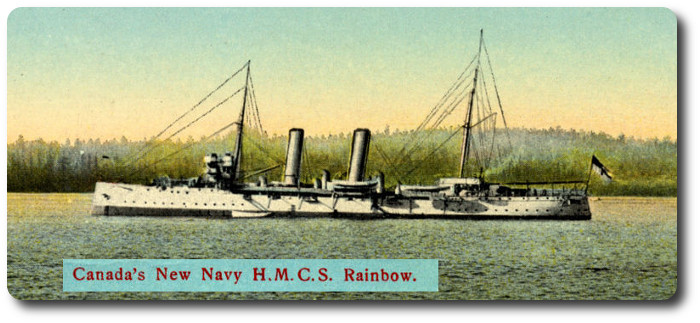

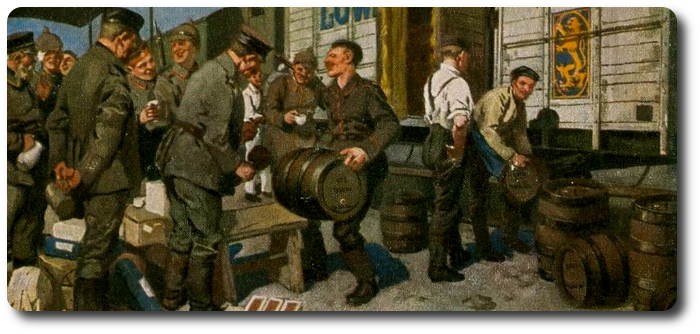

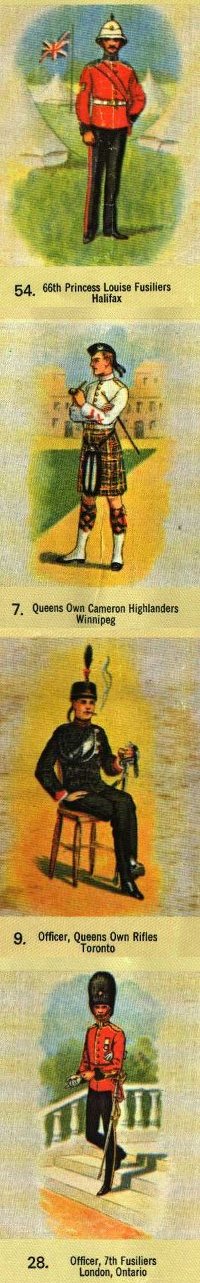

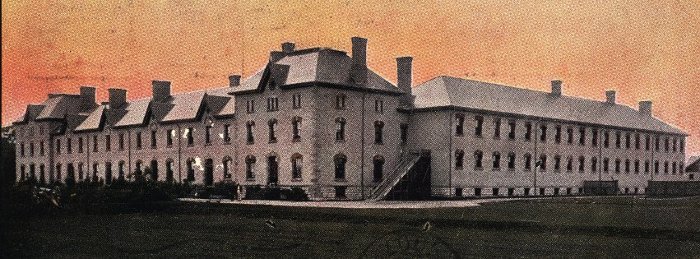

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced.

Ottawa, January 14.—The year's work in the Canadian Militia is reviewed in the annual report of the Militia Council presented by Colonel the Hon. Samuel Hughes. The one object sought, says the report in part, was preparedness for war, the power to mobilize at short notice a force of adequate strength, well-trained and fully equipped. In the scheme of defence a few adjustments have been made, but no important changes introduced. "The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."

"The main obstacles to our efficiency," remarks General Otter, "present themselves in two forms—lack of money on the one hand and the profusion of it in the form of successful enterprises on the other. The former, militating against the provision of armories and equipment, rifle ranges and training grounds, and so placing obstacles in the prosecution of effective training in its full significance; the latter prevents individuals from sparing the time necessary to fit themselves for the military duties they have assumed."