Topic: Army Rations

What Soldiers Have For Food (1914)

The Day, New London, Connecticut, 16 October 1914

The suffering from hunger said to have been experienced by great numbers of German soldiers during the present war is alleged in the news despatches to have been due largely to the fact that they were not provided with emergency rations. This, if true, is certainly surprising, inasmuch as the Kaiser's troops are ordinarily supplied with the best of all concentrated food, in the shape of "erbswurst," or pea sausage—a species of provender so sustaining, and furnishing so much nourishment in small bulk, that the Prussians 44 years ago declared that without it they could not have endured as they did the fatigues of the rapid campaign against the French.

If such value is this peas sausage as a war food that an effort was made to utilize it in the British army. But Tommy Atkins would have none of it—illustrating the fact that a ration found suitable for the fighting man of one nation is not necessarily acceptable to those of another. A war food must be not only wholesome and nutritious, but also palatable, and national tastes in matters gustatory differ. Some years ago an attempt was made to introduce in the German army a biscuit composed of meat and flour, but the soldiers refused to eat it.

An emergency or "iron" ration is not meant to be eaten under any ordinary circumstances, but only when the soldier finds himself separated from his command and cut off from the supply train. Then only is he permitted to utilize his small store of condensed provender, which he carries in his knapsack, in order to avoid starvation. For this purpose the German fighting man is provided with a one-pound can of preserved meat, a small quantity of hard bread, and a pea sausage. The same kind of sausage, however, is an important part of the regular ration. It is eight inches long, is wrapped in white cloth, bag-fashion (tied at one end with a string), looks somewhat like a fat firecracker, weighs eight ounces, and its contents emptied into a pot of boiling water, will make 12 plates of excellent porridge.

This kind of sausage owes its invention to a cook, whose rights to manufacture it were purchased by the German government for $25,000. It is composed of pea meal, fat and bacon, with a few other ingredients added for flavouring. The most important point, however, is the method of its preparation, by which it is rendered proof against decay or deterioration. Hard as a brickbat, it will keep perfectly good for years.

The Belgian emergency ration is a ten-ounce can of corned beef, put up in a liquor flavoured with vegetables. For the same purpose the British use a compressed pea soup. At the opening of the Afghan war, in 1878, an enterprising Englishman supplied the army with this product, in the form of a yellow soup, put up in four-ounce cans, bearing directions that the contents be mixed with a quart or so of water and then boiled to the proper thickness. When General "Bobs" made his famous march on Kandahar, his troops were fed almost wholly on this soup, which occupied such a small space that a single mule could carry a day's food for the whole battalion. Subsequently, in the Zulu and other campaigns it was largely utilized.

The popularity of peas as a war diet is attributable to the fact that they are the most nutritious of known foods, surpassing in this respect even lean meat. Another advantage they have over meat is that they afford what is called a "balanced ration," containing as they do both fuel stuff to keep the fighting machine going and "protein" to make muscle and blood. The army soup above described is made by steam-roasting the peas, grinding them fine, adding some beef extract for stock (with suitable seasoning), and reducing the mixture to the smallest possible bulk by elaboration and pressure.

The British army also uses a kind of hard bread which looks something like a dog biscuit, four inches square and weighing three ounces. It is of whole wheat, compressed—a sort of condensed loaf. For the Russian troops in the field is provided a "war bread," the ingredients of which, as well as the process for making it, are a government secret. When a piece of it is put into hot water or soup, it swells up like a sponge, and is said to taste much like fresh bread.

Vegetables are necessary to health. Accordingly, Whenever practicable they are supplied as part of the regular ration of an army. The French have a concentrated mixture of vegetables and meat, which comes in six ounce tin boxes, holding 21 tablets wrapped separately in red paper. One of these, dropped into a pint of boiling water yields a plate of delicious soup.

Onions and carrots are deemed especially valuable. The German army is supplied with carrots evaporated to absolute dryness and granulated to the size of snipe shot. Onions are provided in one pound tins, similarly desiccated. There is much water in onions, so that this quantity of the concentrated vegetable is equal to ten pounds of the fresh. One pound represents a day's ration for 48 men. Cabbages, prepared in the same way, come in four ounce tablets.

The old process of evaporation by heat is not used in the preparation of concentrated vegetables for use by the European armies now in the field, because it incidentally deprives the cabbages, onions, or what not of the volatile essential oils and ethers which have much to do with their flavours. A method of comparatively new invention is employed, the material being shredded, spread on shallow trays, and run on cars into a tunnel through which dry air of only moderate warmth is continually passing. The dry air sucks the moisture out of the vegetables, which, when out up in tine with screw tops, will keep indefinitely. When wanted for use, it is necessary merely to restore the water, incidentally to cooking. The taste like fresh vegetables. Soup greens preserved as a mixture in this fashion are particularly good.

The main standby of the Japanese troops now moving against the Germans in the far east is rice—not supplied in the raw state, be it understood, but cooked and there-upon made water free by evaporation and pressure. It is furnished to the soldiers in the shape of balls, one of which, dropped into a pot of boiling water in camp, affords a hearty meal for several men. Or if preferred, the balls may be cut into slices and roasted.

Another item of the British rations is desiccated beef, one ounce of which is equal to five ounces of ordinary meat. It is absolutely water-free, and so hard that the fighting man can hardly cut it with a jack-knife. He chops off a small hunk of it, puts it into a little machine resembling a coffee mill and grinds it up. It comes out in small shavings, which may be eaten on bread or used for soup stock. Two ounces of this beef will make soup for eight soldiers.

Mutton is supplied in the same way, in little rectangular blocks three inches long, two inches wide, and one inch thick. A manufacturer in England who puts up such concentrated food for army use says that he can compress the edible parts of ten sheep into the bulk of one cubic foot. Into the same space he can condense 3,000 eggs, rendered water-free by evaporation and reduced to the hardness of a brick by hydraulic pressure.

The news despatches a few days ago stated that the German crown prince had wired to Berlin for large supplies of tobacco, needed immediately for his troops. An American woman in London gave $20,000 to the British war fund, expressing a wish that the money be spent in the purchase of "chewing" and "smoking" for the soldiers of the expeditionary force now fighting in France. There is no doubt that the idea was an excellent one, judging from an opinion expressed on the subject not long ago by our own military authorities.

The bureau of subsistence of our war department, in an official report said: "Under the influence of tea, coffee or tobacco a man seems to be brought to a higher efficiency than without them. They keep up cheerfulness and enable soldiers to endure fatigue and privations, while deprivation of them may cause depression, homesickness, feebleness and indeed may lead to defeat in battle. Depressed troops do not fight well. A wise military leader will see to it that he men are not deprived of tobacco, or he will regret his carelessness.

The British soldiers now fighting in France, privates as well as officers, take their cup of tea regularly. It is a national habit which even battles can hardly interrupt. Also, the commissariat provides candy, which the men are encouraged to buy. In our own army candy (a highly concentrated kind of food) is supplied—not chocolate creams and bonbons, of course, because they too are perishable, but such sweets as lemon drops, hard gum drops and chocolate.

The enormous total quantity of provender required to supply armies that number millions of men may be judges from the fact that in 24 days a soldier consumes just about his own weight in food and water. Half the water he takes into his body is in the food, the other half is drink. The total dry matter in the food consumed daily is in round numbers one per cent of the weight of the body. Thus in 100 days a man weighing 150 pounds will absorb his own weight of dry matter—not reckoning, that is to say, the water his food contains.

Speaking of water, it is curious how many different solutions of the canteen problem have been found by various nations. The canteen carried by the British soldier is of glass, covered with canvas. That of the Italian fighting man is of wood, while the Spaniard's water vessel is a goatskin. The regulation canteen os the United States army is of tinned iron.

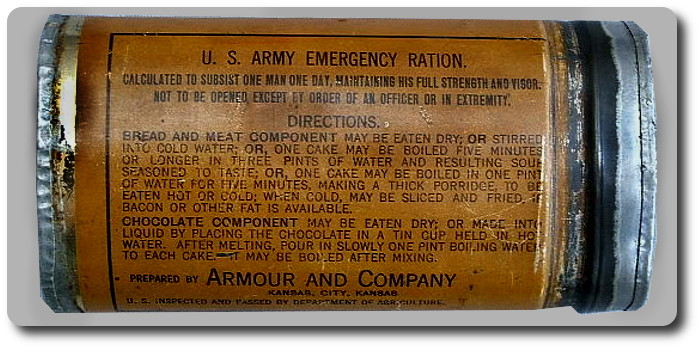

For emergency rations our own army formerly used a mixture of dried lean meat and toasted cracked wheat. This, deprived of moisture and pressed to the hardness of a brick, was put up in three packets, each containing also a tablet of chocolate—the whole representing one day's meals, to be carried in the knapsack.

Special machinery was required to put the stuff up, and the war department, in order to make it worth while for the manufacturer to produce it, was obliged to order it each year in large quantities. It had to be used up somehow and, to get rid of it, was fed out to the soldiers at army posts, who were thus obliged, however unwillingly, to consume emergency rations for their regular meals. As may well be imagined, there was much grumbling.

In 1910 a new kind of emergency ration was adopted. It was a mixture of chocolate, sugar, egg and malted milk, put up is such a shape as to look like ordinary commercial chocolate, in flat cakes wrapped in tinfoil. Three cakes, three meals. Weight, 12 ounces for the three, including the can containing them.

What has already been said will serve to show that the soldiers of the various armies now fighting in Europe are much better and more luxuriously fed than troops in any previous war in history. It costs money, but it pays; for, other things being equal, it is the well fed man that wins in battle, when opposed by an under-fed adversary.