Topic: British Army

It has been well said that a soldier's best qualities are displayed in the field; his worst in quarters.

"Tommy Atkins's" Career

Part III - (Vide illustrations)

The Sydney Mail, New South Wales Advertiser, 25 March 1882

By P.L.M.

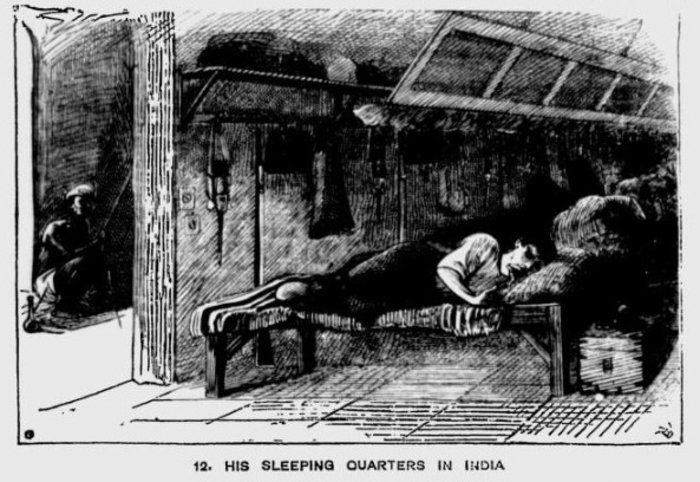

In India the soldier is drilled chiefly in the early morning, for the intense heat will not allow of military exercises during the day; and he not only escapes these, but is allowed a noon-day sleep. In illustration 12 we see him enjoying this, and we observe that his object now is to reduce his coverings to a minimum; doubtless he sighs for dear old England with its ice and snow, sludge and fogs. The barrack-room is rather more commodious than that of the old country, and it is ventilated by means of punkahs (wooden frames with curtains attached) one of which is slung over each bed, and they are kept in constant motion by native labourers, or "coolies." The temperature of the room has been further reduced by means of "latties" hung over the open apertures of the barrack-room on the windward side. These are lattice frames, filled in with a soft substance called kus-kus, which is constantly kept wet. Altogether Tommy's comforts are attended to upon a much more liberal scale than that which prevails in Europe "and still he is not happy."

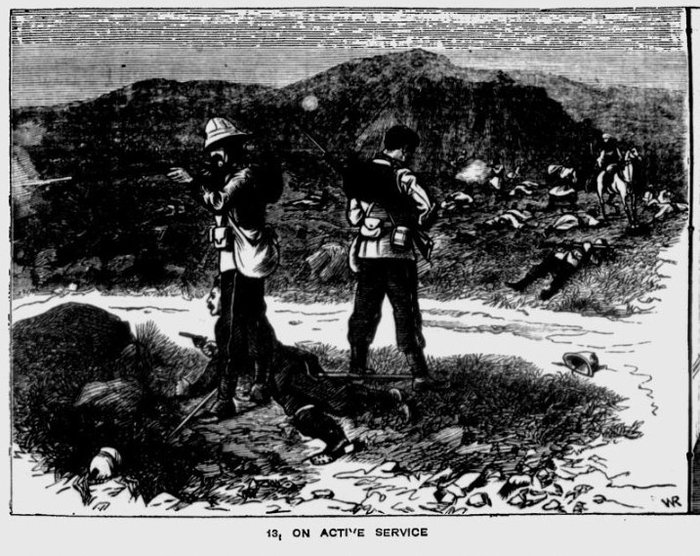

It has been well said that a soldier's best qualities are displayed in the field; his worst in quarters. In a former picture we have seen him a drunken lout; an intoxicated ruffian, assaulting the police, and carried off to durance vile, like an insensate brute. In illustration 13 we see him as a hero; the impersonator and embodiment of the British bull-dog. War has broken out, and Tommy Atkins with a small party finds himself on some wild hill-side surrounded by a horde of howling gesticulating savages, as well versed in the use of the rifle as he is himself, and of dauntless courage. Private Atkins and his comrade are covering a wounded officer, who is prostrate upon the sward, but continuing to protect himself and assail the dusky foe with his six-shooter. Let us hope that Tommy and his friends will prove victorious. We wish that in all our recent galling little wars, he had always displayed himself as valourously; but, alas! The heights of Isandula, and other scenes of conflict are hard and stubborn facts to the contrary, and raise in the minds of military scientists grave doubts as to the policy of short service. In the days of Welling soldier enlisted for "unlimited service," in other words to be the slave of the pipe clay for the period of his natural life, or until shot, maimed, discharged worthless, or sent about his business with a penny-a-day pension, when unfit physically for further duty. Then afterwards he joined for 21 years, which practically amounted to nearly the same thing; for after a man has been so long a soldier, the meridian of his life is past, and it were useless for him to seek to turn to other employments, Now a days, a man may enlist for "short service," which means (in the infantry) six years with the colours, and six in the reserve, so that fresh blood is constantly being infused into the army; but the iron man of former days, the "hero of a hundred fights," the fellow who "soldiered" all over the world, the trustworthy, skilled, and experienced non-commissioned officer, where are they? The former almost extinct, the latter but little more numerous.

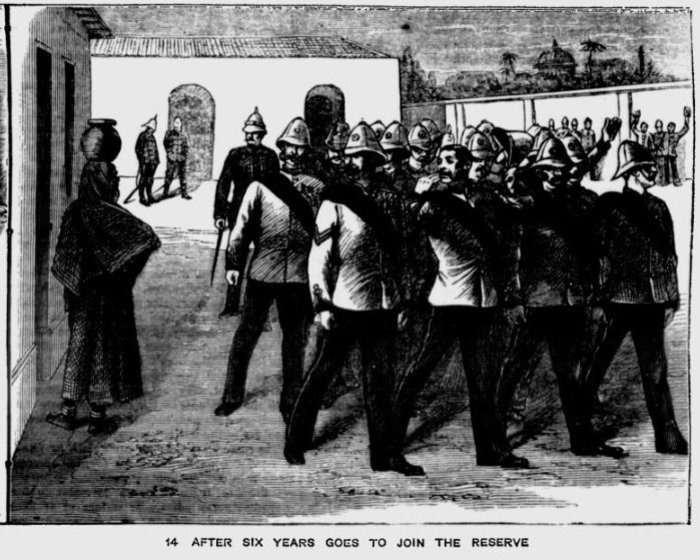

In illustration 14 we see Tommy Atkins in the pride of his manhood off to join the reserve, his six years' service having expired. In the stalwart, sturdy, moustached soldier of this picture is presented a marked contrast to the awkward lad first introduced to the reader, and it certainly seems a pity that his country should lose practically the benefit of his services just as they have become most valuable. The day may yet arise when the British Government will bitterly regret haiving infused into our army so large an element of young lads, untutored, and unswayed by association and the examples of veterans in their own ranks.

Having thus briefly sketched the career of the British private soldier as depicted by the artist, possibly a few words on the subject of the colonial "Tommy Atkins" may not prove unacceptable to our readers.

The only regular military force in this colony is that popularly, though erroneously, known as the "Permanent" Artillery; the proper designation of this corps being "The New South Wales Artillery," such being the title bestowed upon it in the various Government Gazettes under which the three batteries of which it is composed were raised. One battery of Artillery and two companies of Infantry were originally established under a statute known as the "Naval and Military Forces Act," of 1871. By this enactment authority was given to the Government to raise regular Naval and Military forces; and it was provided that the latter should be subject to the Imperial Mutiny Act and Articles of War for the time being, as well as the "Queen's Regulations" for the control of the army. When the Mutiny Act and Articles of War were superseded two years ago by the "Army Discipline Act," that also was adopted in the colony. Our little "army" is therefore in all respects a "regular" one, and in point of drill and efficiency, may challenge competition with any regiment in the Imperial Service. Indeed such distinguished officers as Sir William Jervais, R.A., Colonel Scratchley, R.A., Colonel Dounes, R.A., General Michel, R.A., and many others visiting the colony have expressed surprise at finding in this remote quarter of the globe, three batteries established upon a basis so perfectly akin to that of the Royal Artillery. The training of the men and the establishment of a system of interior economy conducive to this end, has been especially the object of the commanding officer, Colonel C.F. Roberts (late Major R.A.). The first officers appointed were Captains Airey and Spalding (both late R.M.). The first and only officers of the Infantry were Captain (Brevet Major) Fitzsimmons, Captain Heathcote, V.C., and Lieutenants Wilson, Strong, Underwood, and Chatfield. The two splendid companies of which this corps was comprised ceased to exist on December 31st, 1872, having been disbanded by Legislative action. The Artillery, however, were spared, and in 1876 a second battery was added; a third in 1877. At that strength the force has since remained.

The Colonial "Tommy Atkins" enlists for five years' service in almost exactly the same style as his Imperial prototype, save that it has not been found necessary to beat up for recruits with a recruiting-sergeant. He therefore applies to the adjutant at the brigade office, Dawes Battery, and if the responses to the questions addressed him prove satisfactory, he is sent to the medical officer (Surgeon-Major W.G. Redford) for examination touching his physical fitness. Care is taken to obtain none but men of good antecedents, and "sound wind and limb," and it is no exaggeration to state that half the candidates for the force are rejected by the adjutant, and two-thirds the remaining half by the medical officer. The limit of age is between 17 and 35, but exceptions are occasionally made in the case of old soldiers having good discharges. It may readily be conceived that with such precautions the forces comprises a fine stalwart body of young men; and indeed this is absolutely necessary, for our artillerymen have occasionally to "rough it" pretty considerably and perform some very hard work.

Having passed the ordeals alluded to, Tommy Atkins is regularly attested before an officer, and usually granted a 24 hours' pass to make his arrangements prior to joining. He is in many respects much better off than the Imperial soldier. His pay is 2s. 3d. per diem, or double that of the British mine-man; his rations include a liberal allowance of meat, bread, vegetables, tea, coffee, butter and groceries; and he receives "a free kit" comprising his uniforms, greatcoat, boots, and underclothing, besides such necessaries as brushes, knife, fork and spoon, haversack, hold-all, &c. In fact he receives everything that a soldier can require; and his tunic and trousers are composed of a cloth superior to that issued to the British private. In return for this, however, the scale of fines for drunkenness is exactly double that of the Imperial service; and stoppages for articles lost by neglect, &c., are made having the same consideration in view.

Space does not admit or our giving a detailed account of the general routine of an artillery soldier's life; to do that we might well issue a special number. Suffice to say that as soon as Gunner Atkins joins, his work begins. He first goes through the routine of squad and setting-up drill, manual and firing exercises, and guard-mounting; he then proceeds to learn gunnery, and he is not considered dismissed in this until he has acquired a fairly competent knowledge of the drills appertaining to the 10 inch, 9 inch, and 80 pound M.L.R. guns, the 40 pound B.L. Armstrong, and the field gun, besides repository drill, comprising the mounting and dismounting and shifting of ordnance, &c. It may readily be imagined that this involves some time, and so it does; for it is rare than an average gunner can be made under about 18 months even with assiduous training. Whilst his military education is going on, he is of course becoming indoctrinated into the interior economy of a soldier's life, and taught habits of order, cleanliness, and discipline. If he be fond of soldiering and attentive, his life is a happy one enough; he need never be in trouble if he choose to abide by the regulations, which are not needlessly stringent, and his duty will become a pleasure. The lazy, unprincipled, or insubordinate, or those given to excess in liquor, however, will find their lines by no means cast in pleasant places if they join the N.S.W. Artillery. For them remain the guard-room, the defaulter-drill (of which we have already seen an illustration), the cells, and the Provost prison; besides fines, stoppages of pay, and minor punishments ad libitum. By a very wise provision also the Governor has been empowered, upon the recommendation of the commanding officer, to dismiss summarily as "worthless and incorrigible characters," any black sheep whom it may be deem undesirable to retain in the force. By this means the "bad character men" may be said to have been extirpated; and serious misconduct is a thing of rare occurrence.

That our N.S.W. Artillerists are well versed in their profession, the harbour guns they have mounted, the military works they have executed, and their well-known proficiency in drill are the best witnesses. Certainly in point of physique, intelligence, and conduct, it may well be doubted whether there are any three Imperial batteries to equal them; and whilst it may be conceded that 300 odd men are withdrawn from industrial pursuits, it is equally true that many a young man has found himself immensely improved at the end of his five years' service; and incalculably better fitted for civil life. Many of those taking their discharges with good characters are received into the police, or become warders in gaol, tram-guards, &c.