Topic: Canadian Army

But, alas for the depravity of human nature! The young soldier is, in the majority of cases, not long before he gets into trouble.

"Tommy Atkins's" Career

Part I - (Vide illustrations)

The Sydney Mail, New South Wales Advertiser, 11 March 1882

By P.L.M.

The designation "Tommy Atkins," familiarly applied by military men to the British private soldier, is of very old standing, having been in use long before the Duke of Wellington's time and probably extending back to the days of Dettingen and Fontenoy. It took its origin from the circumstance that at one time all military forms set forth by authority as precedents for use in the service were headed (for instance), "Attestation Sheet of Thomas (or Tommy) Atkins," "I, Thomas Atkins," and so forth. In this manner Private Thomas Atkins played the same conspicuous part as that mysterious pair Messr John Doe and Richard Roe used formerly to do in legal phraseology; and the sobriquet "Tommy Atkins" came into universal acceptance as the equivalent of the private soldier, just as "John Bull" has become accepted as the typical Englishman.

The recruiting sergeant has for very many years played a conspicuous part in the enrolment of embryo heroes for the British army, and has always been characterised by shrewdness, acumen, and a profound knowledge of that species of human nature which it is his province to encounter. Many witty dramatists and novelists of the last century, and not a few of the present, have furnished amusing sketches of his various artful contrivances for persuading unwary yokels to "accept the shilling." During the 18th century the process of recruiting was somewhat summary. Immediately the mystified, or inebriated, or deluded countryman had been cajoled into allowing the old coin within his palm, he virtually became a soldier, and was taken, directly he was in a fit state, before an officer or a justice of the peace to be attested, when he was at once hurried away to his regiment. In our days the process is somewhat more circumlocutory. The recruit, haiving received the "Queen's shilling," which constitutes enlistment, is furnished with a copy of the War Office form desiring him to appear before a certain justice of the peace, at a certain time, to be attested; i.e., to have an oath administered to him, the nature of which is that he will bear faithful allegiance to her Majesty, her heirs and successors; and to declare that he has never previously served in the army, navy, or militia, and that the information he has given the recruiting sergeant with regard to his birthplace, &c., is correct.

The attesting or swearing-in is ordered not to take place until 24 hours after the enlistment or reception of the shilling, nor until the recruit has been passed by a doctor as physically fit to serve. This 24 hours' grace gives the man the chance of changing his mind; he is still at liberty, when appearing for attestation, to pay back the enlisting shilling, with 20s. "smart money," and any other pay and allowances he may have received, and go free. This holds good for 96 hours from the time of enlisting. Failure to appear, however, he is liable to be punished as "a rogue and a vagabond."

It will thus be perceived that the recruit has many more chances nowadays than he was allowed by the regulations of our ancestors, who procured "food for powder" in a manner rather expeditious than formal. The recruiting sergeant is still, therefore, as of yore, selected from amongst the smartest non-commissioned officers in the regiment. He must be a man of pre-eminent address, of immense volubility, intense capacity for gasconading, and a ready wit, enabling him to solve all doubts that arise on the minds of those on whom his is plying his powers of persuasiveness, and respond to all their queries in a manner calculated to carry conviction to the most vacillating. The creed he enunciates if\s "Gory" in the military sense of the term; and of course his doctrine is that all civilian modes of gaining a living are despicable, and that the only ladder to distinction is that which bears the soldierly grades as its rungs.

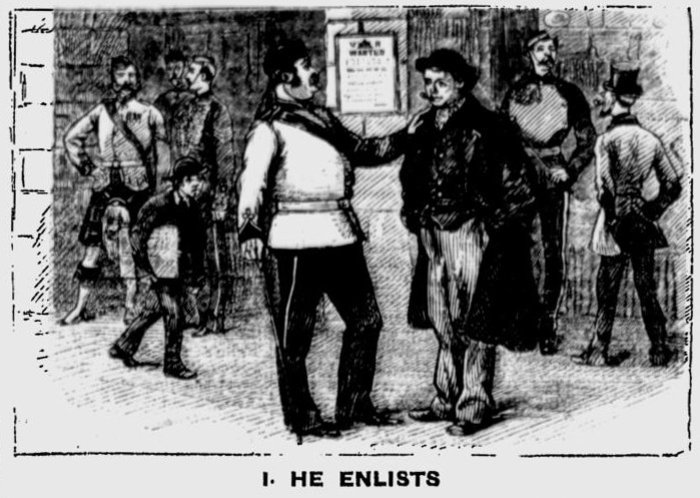

Our illustration (No. 1) represents a group of recruiting sergeants assembled, probably, somewhere in the vicinity of Whitehall, and a "likely lad" in undergoing the process of being angled for. The treble-striped fraternity represent the three branches of the profession, "horse, foot, and artillery;" for they comprise a dashing lancer (who also has a candidate under surveillance), a gaudy horse-artilleryman, and a Highlander in the garb of old Gael; besides the bluff linesman in the foreground to whom the younger fellow with the pipe seems already half inclined to surrender. We can imagine the persuasions of this modern "Sergeant Kite." "Look at me," he seems to say; "observe my portly figure denoting ease and good living; remark my handsome and comfortable uniform! There's the life for you, my boys! Plenty to eat and drink, and money to spend, and her Majesty's uniform to wear, and nothing to do but amuse yourself, and pepper the blacks and foreign parts just for diversion. Join us, and it'll be the making of you; you'll be a colonel in a few years. What d'ye say? You will? There's a lad of spirit; put that shilling in your pocket, my boy, just to begin with."

It would be hard to surmise the origin of the lad he is addressing. Some indolent young citizen, apparently, who has made up his mind that commercial pursuits are not his vocation, and that a life where he has everything found and nothing to do will just suit him. In adopting a military career with the latter idea, however, he makes a terrible mistake, as he has yet to discover, when he runs the gauntlet of drill, fatigues, guards, picquets, barrack-room work, kit-cleaning, orderly duty, &c., &c. However, he enlists.

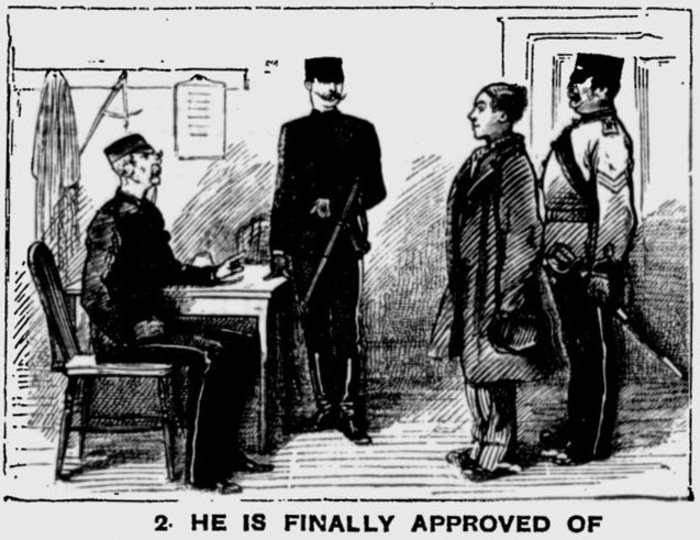

We presume that he has been duly passed "fit" by the medical authority, and that he has entirely exonerated himself from opprobrium as a "rogue and vagabond" by taking the attestation oath—for illustration No. 2 depicts him as brought before the commanding-officer and adjutant of his corps, under charge of the sergeant-major, by whom he has already been instructed to "stand to attention" in the dread presence. By the commanding-officer he is interrogated as to his name, age, trade, whether he is married, and whether he has ever served before, &c. If approved, he is measured, posted to a company, clothes, and receives "a free kit," or the outfit comprising such necessaries as a soldier is supposed to require. In the picture, the colonel, pince-nez duly mounted, is putting the requisite question; and the apartment is marked by that hardness and lack of convenience which seems to characterize orderly-rooms generally.

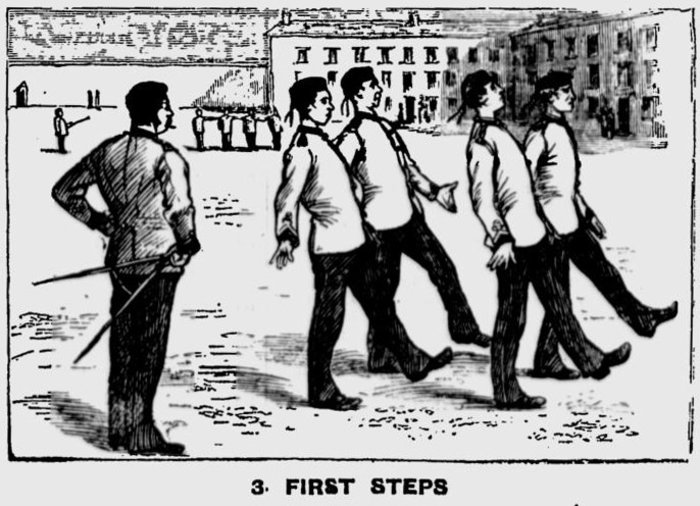

"Tommy Atkins," having been finally approved of, is sent to drill and illustration No. 3 represents him in the barrack-square undergoing the torments of "first steps" with other comrades of the "awkward squad." Such of our readers, as are or have been volunteers, will have a vivid recollection of the "goose-step," or (in the more dignified military phrase) "the balance step without gaining ground," followed by the "balance-step gaining ground," with the instructor's "One, two, three, four—one, two, three, four—one, two, three, four—Now, you've got it—Hang you, keep it," &c., &c. These are varied by "extension motions," for the purpose of expanding the chest and giving play to the muscles, in which the man has to touch his toes with the tips of his fingers, work his arms like the sails of a windmill and perform divers other refreshing exercises. The squad before us is certainly an angular one, and it may be safely predicted that the instructor who is drilling them, pace-stick in hand, has still a great deal of work before him. The object of the pace-stick is to measure off the length of the step, so that the recruit does not exceed the regulated number of inches, and this acquires at length the habit of invariably using the service pace of 30 inches in slow or quick time. In the distance may be observed another squad, who are being taught how to take up an accurate "dressing" in the ranks.

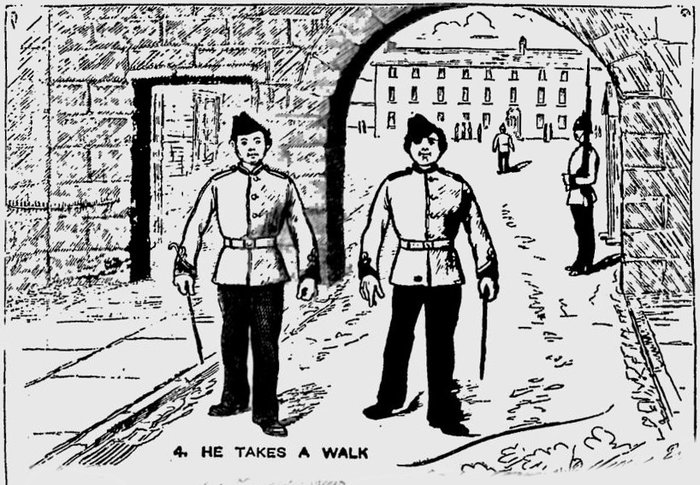

However, all things come to a termination; and this in illustration 4 we find Tommy and a comrade out for a walk. They have evidently proved apt pupils to the regimental teachers, for they are now well "set up," and have learned to wear their uniforms with the jaunty air of the soldier. The uniform is that of then line, and they are equipped in their regulation attire for the streets when not on duty—namely, tunic, waistbelt, Glengarry cap, and cloth trousers, whilst each one flourishes the light cane, which is all the regulation permits him to carry. Doubtless most recruits on finding themselves to duty, and fully clothed, feel not a little vain, and strut along the streets with no inconsiderable sense of their imposingness, especially in the feminine eye.

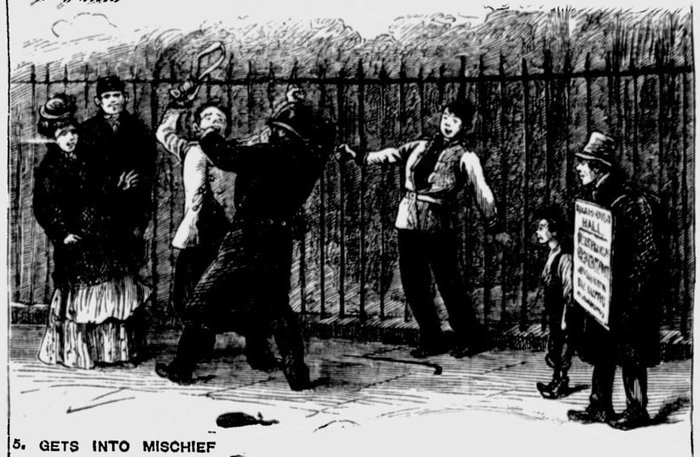

But, alas for the depravity of human nature! The young soldier is, in the majority of cases, not long before he gets into trouble. He falls into bad company, swallows and abnormal quantity of malt-liquor, and rapidly becomes ripe for "a row," yearning to display upon somebody his capacity for belligerent purposes. Neither is it long, usually, before he is accommodated. Illustration 5 represents him as engaged in a fight with the police.

The worthy civil custodian of las has seized the inebriated son of Mars with a tenacious grip upon the throat and left arm; while the soldier who has still his right at liberty, is giving the policeman a mauling with his belt. The waistbelt of the private soldier makes a most formidable weapon when used as depicted, and is one of which he is but too apt to avail himself if he gets into a disturbance. To such an extent is this carried on, that in many regiments there is an order prohibiting all except men of good character from wearing their belts when not on duty. The old soldier, however, seldom misuses his accoutrements in this manner. It is chiefly the raw material, such as represented in the picture.

The fighting soldier's comrade, who is very far gone in liquor, is clutching the rails to keep himself from falling; and on the left may be observed two disreputable civilians, who have, probably, in the origin had a good deal to do with the fracas.

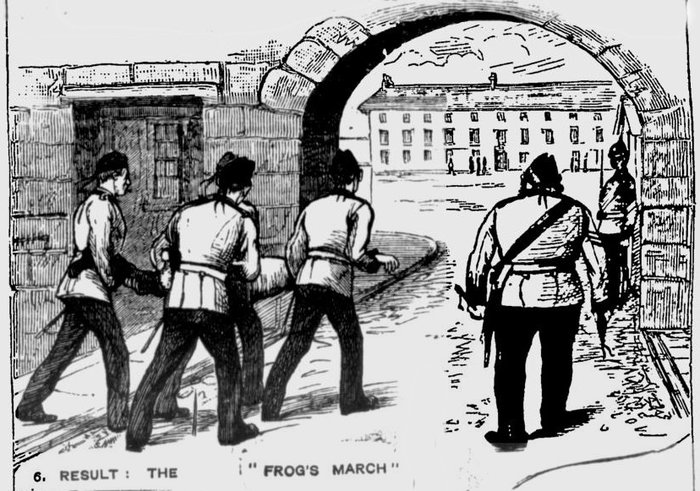

Tommy Atkins is not, however, to be consigned to the station this time; for in illustration 6 we find that a picket of his regiment has arrived upon the scene, made him a prisoner, and are in the act of conducting him to the guardroom by a simple but most unpleasant expedient for compelling locomotion, entitled "The Frog's March." This consists simply in turning the rebel over on his face, when four men each take a leg or an arm, whilst a fifth sits on him if he attempts to rise; and thus he becomes perfectly helpless. The corpulent non-commissioned officer in command of the party is carrying the offender's Glengarry and belt.

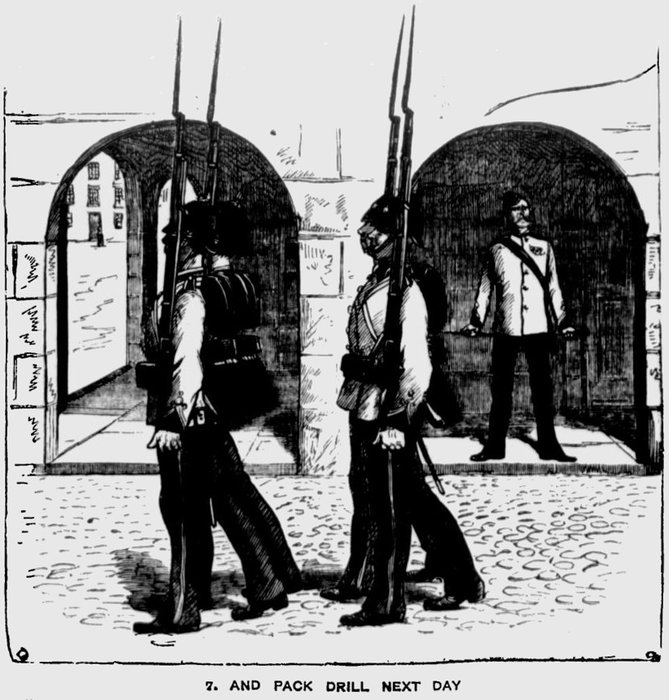

After 24 hours of "suffering a recovery" in the seclusion of the guardroom, Tommy Atkins, having been paraded before the medical officer, and been by him marked "fit," is brought into the awful presence of his commanding officer, and hears the bead-roll of his iniquities duly recounted. As this is a flagrant case, he gets a term of "confinement to barracks," which involves "pack," or "defaulter-drill" (illustration 7). The defaulter, having to fulfill all ordinary duties, attend parades, &c., has to do not more than four nor less than two hours' "defaulter drill," administered an hour at a time, per diem. This is done in full accoutrements, belts, helmet, greatcoat, haversack, &c., in fact "heavy marching order." He has also to answer his name at intervals of hand-an-hour (when not actually on drill) all day long; thus it may truly be admitted that "taking one thing with another, a defaulter's life is not a happy one."

Our illustration depicts him with his brother delinquents performing their defaulter drill, under the auspices of a severe-looking sergeant.

(To be continued.)