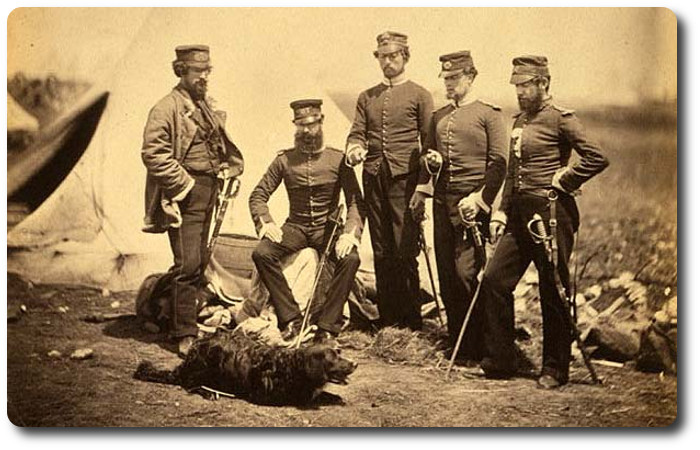

Topic: Officers

The Routine of Military Life

An "Officers' Mess" in the Crimea

The Newfoundlander, 25 January 1855

The correspondent of the Morning Post gives the following account of military life in the camp:—

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

"Let me briefly tell you how the day is passed. Early in the morning, generally at half-past four, there is a scraping at the tent door, and a voice is heard, "Signoir alzate, vi prego, in cafe a pronto," to which a lisping voice responds, "What Thpero, it ith'nt five, thurely?'…'Si, signoir, vbicino a'le cinque,' cries the faithful old idiot (our best servants have been in lunatic asylums), and the British officer is soon up and doing, his coffee is drunk, biscuit and pork are consumed, a wallet is thrown across the shoulder, containing provender for the day, and a flask of rum; the sword is girt on, and away goes out companion to the trenches, there to remain until 6 p.m., leaving us to snooze away until the sun has afforded us a cheering supply of light and heat, when we rise from our bed of blankets, and, having drunk in pure air during the night, rush to breakfast with ravenous appetites.

The breakfast table, made of two pieces of plank, nailed upon four stakes, is covered with tin spoons, tin pots, tin plates, tin canisters, and all those little tin articles for salt, pepper, &c., so well known to campaigners; and when we are seated, waiting anxiously, like hungry coach travellers of old, in comes a fine-faced finger-begrimed soldier, with a large supply of fried pork or beef frizzling from a black frying-pan in one hand, and in the other hand a cargo of soaked biscuit which, to give it flavour, has been baked in the fat of ration pork; this, with now and then a potato, or onion for a change, and a cup or two of coffee, forms our breakfast.

The pipe, that indispensable friend of the soldier in the field, follows every meal pour exciter la digestion; rud [sic] after it, should no duty (rare occurrence) call us away, each employs himself as inclination prompts; but the soldier can never be certain of a moment's quiet, for, not seldom when an affectionate son has settled himself expressly to soothe the anxiety of a worthy parent, an officer is seen pacing over from the commandant's tent. The scribe looks at him with awe, and, as he approaches, asks breathlessly, 'For whom are you looking?' to which the dreaded answer is given. 'You are the man for me, sir. The colonel wants you to take half a brigade of Sappers, and go to complete the cutting in the Inkerman road; it has not, he considers, been thoroughly done.' Of course, go the subaltern must and without a moment's delay, and at the road he is engaged until sunset, with his clothes drenched with rain, and rum and ration pork his best friends.

Our regular dinner hour is three, and as we have a mess of five, ours is strictly military time. As to what we get for dinner, that depends very much upon circumstances, but we generally have a good meal, as we go upon the principle that the best preserver of health under our sharp trials of constitution is good and regular food, and therefore that it is wiser to have a well-supported body rather than a richly supplied purse; and what laughing and joking is there over the reeking camp-kettle! One is accused of taking all the meat, another of forgetting that the delicacies of the season cost money; a third is placed under arrest for consuming more than his ration of grog; indeed, each in his turn is voted a robber of his neighbour and all that with such perfect good humour, that we are like the family in Trafalgar-square, for the slightest disagreement is unknown to us. When the dinner is over; and the ration coffee (far from bad) in tavola, a voice is heard in the distance, 'Thpero, puth the dinner ready, for I cannot thwait—I'm ravenous,' Spero knows well the voice and the order, and at once exclaims—'Momento, Signior, moment! Pranzo subito, subito!' and with lightning speed the pot reappears, and right good pranzo the man of the trencher makes. In truth, pure air works wonders upon the dyspeptic stomachs, and, with us even the hypochondriac finds himself hungry; imagine, then, how an officer just in from the open air, one who has never known a day's sickness, how he eats and drinks; yes, and as he enjoys his food, thanks God for his mercy. By the time the last dinner course is over, darkness has well set in; then it is that we all gather beneath the canvas and talk over the occurrences of the day—and very pleasant chats they are, save when the loss of some officer causes a damp to come over us all."