Topic: Commentary

"A short chamber Boxer Henry point 45 calibre miracle"

The military affectation for complicating language.

Colour Sergeant Bourne: It's a miracle.

Lieutenant John Chard: If it's a miracle, Colour Sergeant, it's a short chamber Boxer Henry point 45 calibre miracle.

Colour Sergeant Bourne: And a bayonet, sir, with some guts behind.

" It is worth noting that one of the tests used by the Germans for admission to officer rank is the ability to translate the technical language of the instruction books into everyday words understood by the average recruit."

The above quote, as many will recognize, is from the move Zulu. More than a humorous line of dialogue, it also captures a stereotypical affectation of some soldiers; the fetishization of technical detail.

Many professional soldiers have successfully completed careers without obsessing over details that were not part of their decision-making processes, at either the tactical or strategic level. They dispensed with what they considered useless knowledge to focus on the important factors that led to success. Clearing their mind of clutter, even the clutter that the training system puts there, was essential for them to achieve their goals.

Knowing how many rounds are in your magazines is important when you're reaching for the next one. Knowing how many lands and grooves are in the barrel of your rifle is not. Knowing how many tanks the enemy is approaching your defensive position, gained from real time intelligence is inherently valuable. Knowing exactly how many tanks are in his higher doctrinal organization is not, and can always be found in a reference if needed. (Notably, in stories many of my generation heard of the Staff College experience of our seniors, mixed amongst the tales of drunken battlefield tours in Europe were always the struggles to memorize, down to the smallest detail, each Soviet Army divisional organization.)

Armies, and not just the Canadian Army, tend to put technical trivia and jargon into publications, and then, in turn, makes those details part of formal classroom instruction. A soldier doesn't need to read a PowerPoint slide to learn how heavy a weapon system is, and each of it's parts to the gram. He would better use that time carrying it to understand the realities of the balance and bulk weight problems in moving it (a test that the planners and manual writers would do well to emulate before calling something "man-portable"). The only time the soldier ever uses those memorized numbers is to regurgitate them on a written test, which confirms his ability to memorize facts and exactly nothing about his ability to employ the weapon.

Many military trades are dependent upon knowing, in an instant, what others may consider esoteric facts. That knowledge may be critical to one or another task of that trade, and carries with it functional importance. In these cases, that knowledge is not fetishized, and is taught and tested with due importance.

The fetishized vocabularies of the military, whether of technical details, or the rote memorization and repetition of needlessly complex military publication prose, only serves to slow the learning process, or to create an aura of understanding where little might exist. This confusion between trivia and professional knowledge is increasingly evident in our electronically connected world. How many of us have seen the confused look on a professional soldier's face when some young Call of Duty fan eagerly wants to discuss the technical differences between all of the weapons he has studied and used in that game? And the professional soldier's response? Indifference. Because the gamer's intense readiness to memorize such details has so little overlap with what the professional learned and, further, retained after application of the useful parts of his training.

Admittedly, there are committed detail-minded soldiers whose personal and professional interests encompass every area of technical trivia and detail. For those with interests in small arms, they do know how many lands and grooves, and they know the effects of internal ballistics between different bullets and barrel lengths. But their knowledge and how they apply it within the army (for those in the right appointments) helps to improve weapons systems being placed in the hands of many others who do not need to know those things. They are experts, self-made or by appointment, and their involvement with the knowledge is to embrace the functional, not to simply boast that they know it.

Where the Army goes wrong is when it embeds the trivia and the awkward turns of phrase as the critical knowledge requirements at every level of training. This is when the training approach can impede the learning process. And it's not a new problem:

Technical Vocabulary and Unfamiliar Words

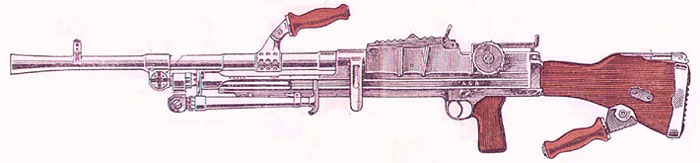

This uninteresting learning of meaningless names of parts is closely associated with a general danger that words unfamiliar to the average recruit will often be used: e.g., in Lesson I (Bren Gun), "gas operated," "tripod," "convertible." I myself was puzzled when told that it was "air-cooled," not having heard before that earlier machine guns were water-cooled. If I had never driven an air-cooled Morgan three-wheeler I should have been still more puzzled.

In an Army instruction film I saw, dealing with anti-tank guns, a sergeant appeared on the film and stated that, at a certain angle of incidence, the bullet would "result in a penetration." Why not "go through"? Why should holes be called "apertures"? Perhaps the best example is the phrase "segmentation to assist fragmentation," which one officer quotes from the description of a Mills hand grenade.

There may, in some instances. be reasons for using less usual words as names, for the sake of rapid identification at later stages; but in early lessons easy words should be used instead of unfamiliar ones, or at least along with the unfamiliar terms as an explanation. In long peace-time training the meaning of unfamiliar terms would gradually sink in, but in quicker war-time training that is not likely.

Some of my students say indeed that instructors at times cannot explain the meaning of words they repeat when they are asked. It is worth noting that one of the tests used by the Germans for admission to officer rank is the ability to translate the technical language of the instruction books into everyday words understood by the average recruit.

- C.W. Valentine, M.A., D.Phil., The Human Factor in the Army; Some Applications of Psychology to Training, Selection, Morale and Discipline, 1943